Publication bias

[5][6] For instance, once a scientific finding is well established, it may become newsworthy to publish reliable papers that fail to reject the null hypothesis.

[2] The nature of these issues and the resulting problems form the five diseases that threaten science: "significosis, an inordinate focus on statistically significant results; neophilia, an excessive appreciation for novelty; theorrhea, a mania for new theory; arigorium, a deficiency of rigor in theoretical and empirical work; and finally, disjunctivitis, a proclivity to produce many redundant, trivial, and incoherent works.

[5] In an effort to combat this problem, some journals require studies submitted for publication pre-register (before data collection and analysis) with organizations like the Center for Open Science.

The largest such analysis investigated the presence of publication bias in systematic reviews of medical treatments from the Cochrane Library.

[25] While there are multiple tests that have been developed to detect publication bias, most perform poorly in the field of ecology because of high levels of heterogeneity in the data and that often observations are not fully independent.

Meta-analyses and systematic reviews can account for publication bias by including evidence from unpublished studies and the grey literature.

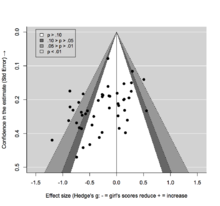

The premise is that the scatter of points should reflect a funnel shape, indicating that the reporting of effect sizes is not related to their statistical significance.

[36][37][38] In ecology and environmental biology, a study found that publication bias impacted the effect size, statistical power, and magnitude.

[39] Ecological and evolutionary studies consistently had low statistical power (15%) with a 4-fold exaggeration of effects on average (Type M error rates = 4.4).

The key feature of time-lag bias tests is that, as more studies accumulate, the mean effect size is expected to converge on its true value.

[26] Two meta-analyses of the efficacy of reboxetine as an antidepressant demonstrated attempts to detect publication bias in clinical trials.

Based on positive trial data, reboxetine was originally passed as a treatment for depression in many countries in Europe and the UK in 2001 (though in practice it is rarely used for this indication).

Publication bias can be contained through better-powered studies, enhanced research standards, and careful consideration of true and non-true relationships.

This can be undertaken by properly assessing the false positive report probability based on the statistical power of the test[47] and reconfirming (whenever ethically acceptable) established findings of prior studies known to have minimal bias.

In September 2004, editors of prominent medical journals (including the New England Journal of Medicine, The Lancet, Annals of Internal Medicine, and JAMA) announced that they would no longer publish results of drug research sponsored by pharmaceutical companies unless that research was registered in a public clinical trials registry database from the start.