Pulcheria

She was the second (and oldest surviving) child of Eastern Roman Emperor Arcadius and Empress Aelia Eudoxia.

Through her religious devotion and involvement in the contemporary ecclesiastical scene, Pulcheria had significant, though changing, influence during her brother's reign.

After Theodosius II died on 26 July 450, Pulcheria married Marcian on 25 November 450, while simultaneously not violating her vow of virginity.

[3] Sozomen reports that much of the rivalry was based on a silver statue of Eudoxia set up outside the cathedral of Constantinople, Hagia Sophia, which Chrysostom condemned: "The silver statue of the empress … was placed upon a column of porphyry; and the event was celebrated by loud acclamations, dancing, games, and other manifestations of public rejoicing … John declared that these proceedings reflected dishonor on the [C]hurch.

They left behind four young children, including Theodosius II, then 7 years of age, who had been his father's nominal co-emperor since 402 and was now sole emperor.

In confirmation of her resolution she took God, the priests, and all the subjects of the Roman empire as witnesses ...[9]It is possible that Pulcheria may have had another motive to remain unmarried, as she would have had to relinquish her power to a potential husband.

In addition, the husbands of Pulcheria and her sisters could have wielded overbearing influence on their young brother, or even posed a threat to him.

Sozomen describes the pious ways of Pulcheria and her sisters in his Ecclesiastical History: They all pursue the same mode of life; they are sedulous in their attendance in the house of prayer, and evince great charity towards strangers and the poor…and pass their days and their nights together in singing the praises of God.

[11] Rituals within the imperial palace included chanting and reciting passages of sacred scripture and fasting twice per week.

[17] Many important events occurred during her time as augusta and her brother's reign as emperor; however, Pulcheria's influence was mostly ecclesiastical.

In a letter from Pope Leo I, a contemporary of Pulcheria, he complimented her great piety and despisal of the errors of heretics.

[18] Pulcheria and Theodosius potentially held anti-Jewish sentiments, which may have contributed to laws against Jewish worship in the capital.

The imperial court called for war against Persia when the Persian king Yazdegerd I executed a Christian bishop who had destroyed a Zoroastrian altar.

[28] Centuries later, Theophanes the Confessor wrote that Eudocia and the chief minister, the eunuch Chrysaphius, convinced Theodosius to rely less on his sister's influence and more on that of his new wife.

This caused Pulcheria in the late 440s to leave the imperial palace and live in "Hebdomon, a seaport seven miles from Constantinople.

[32] As the deceased emperor lacked surviving male children, Pulcheria could bestow dynastic legitimacy on an outsider by marrying him.

[35] In order for the marriage to not seem scandalous to the Roman state, the church proclaimed that "Christ himself sponsored the union and it therefore should not provoke shock or unjustified suspicions.

[37] The First Council of Ephesus, held in 431 in Theodosius's reign, involved two rival bishops: Nestorius, who was Archbishop of Constantinople, and Cyril, the Patriarch of Alexandria.

This conflicted with the religious beliefs of Pulcheria, as she was a virgin empress, and a rivalry between them ensued, during which Nestorius launched a smear campaign against her.

Meanwhile, Cyril had already publicly condemned Nestorius and wrote to the imperial court stating that the doctrine of the "Theotokos" was correct.

At this council, Pope Leo I was the primary advocate for Pulcheria's claims of the doctrine, and he "…forcefully intervened, sending a Tome, a long letter, to Archbishop Flavian of Constantinople, in which he argued for the two natures, but questioned the legality of the recent condemnation of a certain Eutyches for denying them.

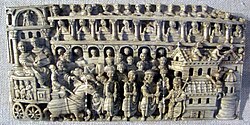

The direction of the wagon's movement inexorably toward the scene at the right, toward the diminutive woman clothed in the rich costume of an Augusta … in it she deposited the holy relics.

"[48] However, this interpretation is disputed,[49] and another opinion is that the ivory shows the later Empress Irene of the eighth century, who sponsored renovation of the church.