Punchcutting

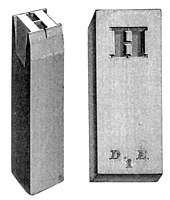

Punchcutting is a craft used in traditional typography to cut letter punches in steel as the first stage of making metal type.

This characteristic is shared by the bronze used to cast sculptures, but copper-based alloys generally have melting points that are too high to be convenient for typesetting.

During the early years of printing, during which the craft and tastes were rapidly evolving, printers often cut or commissioned their own punches.

The technique of punchcutting is similar to that used in other precision metalworking professions such as cutting dies to make coins, and many punchcutters entered the trade from these fields: for instance sixteenth-century theologian Jean de Gagny when commissioning types for his private press in the 1540s, hired Charles Chiffin, known to have previously practiced as a goldsmith.

[9] Among the most famous punchcutters, Robert Granjon began as the apprentice to a jeweller, although Claude Garamond wrote of cutting type since his childhood.

[12] In the eighteenth century, William Caslon took up the craft from engraving ornamental designs on firearms and bookbinders' tools.

[13][14][15] A less common background was that of Miklós Tótfalusi Kis, who began his career as a schoolmaster before paying to learn punchcutting while in the Netherlands to print a Hungarian bible.

[8][18] The process of punchcutting was apparently sometimes treated as a trade secret due to its difficulty and sometimes passed on from father to son.

[16][a] Some testimony to the London Society of Arts in May 1818, which was given as part of an inquiry into developing new banknote anti-forgery precautions, illustrates this.

His employer, Henry II Caslon of the Caslon type foundry elaborated that a font of this size "could scarcely be completed in 7 or 8 months; at present there are only 4 or 5 persons in England who can execute diamond [4pt] type, owing no doubt to the limited demand for it; and the peculiar style of each of these punch cutters is perfectly well known to persons conversant with letter founding."

[2] This gave very precise results and transferred the place of individual creativity completely away from the engraving stage towards a drawing office.

[2] These included Edward Prince, who cut many types for Arts and Crafts movement fine printers, Charles Malin in Paris,[28][23][29] Otto Erler in Leipzig and P. H. Rädisch at Joh.