Punic Wars

[2][6][7] Modern historians consider Polybius to have treated the relatives of Scipio Aemilianus, his patron and friend, unduly favourably, but the consensus is to accept his account largely at face value.

[22] During this period of Roman expansion Carthage, with its capital in what is now Tunisia, had come to dominate southern Iberia, much of the coastal regions of North Africa, the Balearic Islands, Corsica, Sardinia and the western half of Sicily in a thalassocracy.

Approximately 1,200 members of the infantry – poorer or younger men unable to afford the armour and equipment of a standard legionary – served as javelin-armed skirmishers known as velites; they each carried several javelins, which would be thrown from a distance, as well as a short sword and a 90-centimetre (3 ft) shield.

The added weight in the prow compromised both the ship's manoeuvrability and its seaworthiness, and in rough sea conditions the corvus became useless; part way through the First Punic War the Romans ceased using it.

[73] They then pressed Syracuse, the only significant independent power on the island, into allying with them[74] and laid siege to Carthage's main base at Akragas on the south coast.

[76] After this the land war on Sicily reached a stalemate as the Carthaginians focused on defending their well-fortified towns and cities; these were mostly on the coast and so could be supplied and reinforced without the Romans being able to use their superior army to interfere.

[77][78] The focus of the war shifted to the sea, where the Romans had little experience; on the few occasions they had previously felt the need for a naval presence they had usually relied on small squadrons provided by their Latin or Greek allies.

[83] Taking advantage of their naval victories the Romans launched an invasion of North Africa in 256 BC,[86] which the Carthaginians intercepted at the battle of Cape Ecnomus off the southern coast of Sicily.

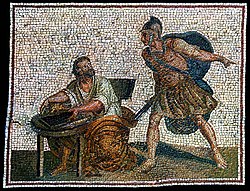

[92] At the battle of Tunis in spring 255 BC a combined force of infantry, cavalry and war elephants under the command of the Spartan mercenary Xanthippus crushed the Romans.

[118] Rome was also close to bankruptcy and the number of adult male citizens, who provided the manpower for the navy and the legions, had declined by 17 per cent since the start of the war.

[120] The Romans rebuilt their fleet again in 243 BC after the Senate approached Rome's wealthiest citizens for loans to finance the construction of one ship each, repayable from the reparations to be imposed on Carthage once the war was won.

[117] Carthage assembled a fleet which attempted to relieve them, but it was destroyed at the battle of the Aegates Islands in 241 BC,[122][123] forcing the cut-off Carthaginian troops on Sicily to negotiate for peace.

The immense effort of repeatedly building large fleets of galleys during the war laid the foundation for Rome's maritime dominance, which was to last 600 years.

This erupted into full-scale mutiny under the leadership of Spendius and Matho; 70,000 Africans from Carthage's oppressed dependant territories flocked to join the mutineers, bringing supplies and finance.

The Roman Senate stated they considered the preparation of this force an act of war and demanded Carthage cede Sardinia and Corsica and pay an additional 1,200-talent indemnity.

[137] Polybius considered this "contrary to all justice" and modern historians have variously described the Romans' behaviour as "unprovoked aggression and treaty-breaking",[135] "shamelessly opportunistic"[138] and an "unscrupulous act".

[146] This gave Carthage the silver mines, agricultural wealth, manpower, military facilities such as shipyards, and territorial depth to stand up to future Roman demands with confidence.

[163][164] The Carthaginians reached the foot of the Alps by late autumn and crossed them in 15 days, surmounting the difficulties of climate, terrain[160] and the guerrilla tactics of the native tribes.

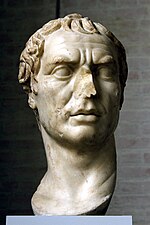

Hannibal arrived with 20,000 infantry, 6,000 cavalry and an unknown number of elephants – the survivors of the 37 with which he left Iberia[74][165] – in what is now Piedmont, northern Italy in early November; the Romans were still in their winter quarters.

In the battle of Cannae the Roman legions forced their way through Hannibal's deliberately weak centre, but Libyan heavy infantry on the wings swung around their advance, menacing their flanks.

[192] Toni Ñaco del Hoyo describes the Trebia, Lake Trasimene and Cannae as the three "great military calamities" suffered by the Romans in the first three years of the war.

The new allies increased the number of places that Hannibal's army was expected to defend from Roman retribution, but provided relatively few fresh troops to assist him in doing so.

[198][199] When the port city of Locri defected to Carthage in the summer of 215 BC it was immediately used to reinforce the Carthaginian forces in Italy with soldiers, supplies and war elephants.

[201] A second force, under Hannibal's youngest brother Mago, was meant to land in Italy in 215 BC but was diverted to Iberia after the Carthaginian defeat there at the battle of Dertosa.

[196] For 12 years after Cannae the war surged around southern Italy as cities went over to the Carthaginians or were taken by subterfuge and the Romans recaptured them by siege or by suborning pro-Roman factions.

[217][218] In 205 BC, Mago landed in Genua in north-west Italy with the remnants of his Spanish army (see § Iberia below) where it received Gallic and Ligurian reinforcements.

[223] The Roman fleet continued on from Massala in the autumn of 218 BC, landing the army it was transporting in north-east Iberia, where it won support among the local tribes.

[224] The Carthaginian commander in Iberia, Hannibal's brother Hasdrubal, marched into this area in 215 BC, offered battle and was defeated at Dertosa, although both sides suffered heavy casualties.

In 205 BC a last attempt was made by Mago to recapture New Carthage when the Roman occupiers were shaken by another mutiny and an Iberian uprising, but he was repulsed.

[262][263] The Roman army moved to lay siege to Carthage, but its walls were so strong and its citizen-militia so determined it was unable to make any impact, while the Carthaginians struck back effectively.