War elephant

[8] The increased conscription of elephants in the military history of India coincides with the expansion of the Vedic Kingdoms into the Indo-Gangetic Plain suggesting its introduction during the intervening period.

Alexander the Great would come in contact with the Nanda Empire on the banks of the Beas River and was forced to return due to his army's unwillingness to advance.

The state of Chu used elephants in 506 BC against Wu by tying torches to their tails and sending them into the ranks of the enemy soldiers, but the attempt failed.

[31] Alexander won resoundingly at Gaugamela, but was deeply impressed by the enemy elephants and took these first fifteen into his own army, adding to their number during his capture of the rest of Persia.

[34] Arrian described the subsequent fight: "[W]herever the beasts could wheel around, they rushed forth against the ranks of infantry and demolished the phalanx of the Macedonians, dense as it was.

The panicked and wounded elephants turned on the Indians themselves; the mahouts were armed with poisoned rods to kill the beasts but were slain by javelins and archers.

Such a force was many times larger than the number of elephants employed by the Persians and Greeks, which probably discouraged Alexander's army and effectively halted their advance into India.

[39] The Seleucids put their new elephants to good use at the Battle of Ipsus four years later, where they blocked the return of the victorious Antigonid cavalry, allowing the latter's phalanx to be isolated and defeated.

King Pyrrhus of Epirus brought twenty elephants to attack Roman Italy at the battle of Heraclea in 280 BC, leaving fifty additional animals, on loan from Ptolemaic Pharaoh Ptolemy II, on the mainland.

In the ensuing battle, near the mountainous straights adjacent to Beth Zachariah, Eleazar, brother of Judas Maccabeus, attacked the largest of the elephants, piercing its underside and causing it to collapse upon him, killing him under its weight.

[48] Since the late 1940s, a strand of scholarship has argued that the African forest elephants used by Numidia, the Ptolemies and the military of Carthage did not carry howdahs or turrets in combat, perhaps owing to the physical weakness of the species.

However, the Lusitanian style of ambushes in narrow terrains ensured his elephants did not play an important factor in the conflict, and Servilianus was eventually defeated by Viriathus in the city of Erisana.

When this unknown creature entered the river, the Britons and their horses fled and the Roman army crossed over"[60] – although he may have confused this incident with the use of a war elephant in Claudius' final conquest of Britain.

The Weilüe describes how the population of Eastern India rode elephants into battle, but currently they provide military service and taxes to the Yuezhi (Kushans).

Local squads which each consisted of one elephant, one chariot, three armed cavalrymen, and five foot soldiers protected Gupta villages from raids and revolts.

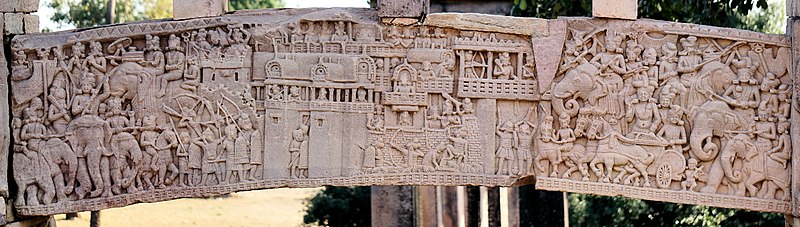

[72] The war elephants of the Chola dynasty carried on their backs fighting towers which were filled with soldiers who would shoot arrows at long range.

The war may have been concluded when the Burmese crown prince Mingyi Swa was killed by Siamese King Naresuan in personal combat on elephant in 1593.

While muskets had limited impact on elephants, which could withstand numerous volleys,[89] cannon fire was a different matter entirely – an animal could easily be knocked down by a single shot.

During the mid to late 19th century, British forces in India possessed specialised elephant batteries to haul large siege artillery pieces over ground unsuitable for oxen.

[91][92][93][94] Into the 20th century, military elephants were used for non-combat purposes in the Second World War,[95] particularly because the animals could perform tasks in regions that were problematic for motor vehicles.

[100] Off the battlefield they could carry heavy materiel, and with a top speed of approximately 30 kilometres per hour (19 mph) provided a useful means of transport, before mechanized vehicles rendered them mostly obsolete.

[101] In addition to charging, elephants could provide a safe and stable platform for archers to shoot arrows in the middle of the battlefield, from which more targets could be seen and engaged.

In India and Sri Lanka, heavy iron chains with steel balls at the end were tied to their trunks, which the animals were trained to swirl menacingly and with great skill.

The late sixteenth century saw the introduction of culverins, jingals and rockets against elephants, innovations that would ultimately drive these animals out of active service on the battlefield.

After sustaining painful wounds, or when their driver was killed, elephants had the tendency to panic, often causing them to run amok indiscriminately, making casualties on either side.

Experienced Roman infantrymen often tried to sever their trunks, causing instant distress, and possibly leading the elephant to flee back into its own lines.

Fast skirmishers armed with javelins were also used by the Romans to drive them away, as well as flaming objects or a stout line of long spears, such as Triarii.

In the 19th century, it was fashionable to contrast the western, Roman focus on infantry and discipline with the eastern, exotic use of war elephants that relied merely on psychological tactics to defeat their enemy.

In the Japanese game shogi, there used to be a piece known as the "Drunken Elephant"; it was, however, dropped by order of the Emperor Go-Nara and no longer appears in the version played in today's Japan.

[111][112] In The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, Mûmakil (or Oliphaunts)[113] are fictional giant elephant-like creatures used by Sauron and his Haradrim army in the Battle of the Pelennor Fields.