Purgatorio

As described in the Inferno, the first twenty-four hours of Dante's journey took place on earth and started on the evening of Maundy Thursday, 24 March (or 7 April) 1300 (Inf.

[7] Forese's case, especially when compared to that of Statius, who has spent over 500 years on Mount Purgatory,[8] shows the power of prayer to aid souls after death.

[5] Ante-Purgatory is the region below the entrance into Purgatory proper and houses two main categories of souls whose penitent Christian life was delayed or deficient: the excommunicate and the late-repentant.

[9] In Purgatorio I.4–9, with the sun rising on Easter Sunday, Dante announces his intention to describe Purgatory by invoking the mythical Muses, as he did in Canto II of the Inferno: Now I shall sing the second kingdomthere where the soul of man is cleansed,made worthy to ascend to Heaven.

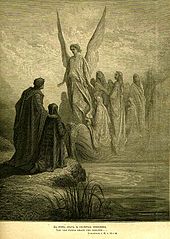

Here from the dead let poetry rise up,O sacred Muses, since I am yours.Here let Calliope arise...[10] At the shores of Purgatory, Dante and Virgil meet Cato, a pagan who was placed by God as the general guardian of the approach to the mountain (his symbolic significance has been much debated).

[13] In marked contrast to Charon's ferry across the Acheron in the Inferno, Christian souls are escorted by an angel pilot from their gathering place somewhere near Ostia, the seaport of Rome at the mouth of the Tiber, through the Pillars of Hercules across the seas to the Mountain of Purgatory.

It is sunset, so Dante and his companions stop for the night in the beautiful Valley of the Princes where they meet persons whose preoccupation with public and private duties hampered their spiritual progress, particularly deceased monarchs such as Rudolph, Ottokar, Philip the Bold, and Henry III (Cantos VII and VIII).

[34] On the terrace where proud souls purge their sin, Dante and Virgil see beautiful sculptures expressing humility, the opposite virtue.

The first example is of the Annunciation to the Virgin Mary, where she responds to the angel Gabriel with the words Ecce ancilla Dei ("Behold the handmaid of the Lord," Luke 1:38[35]).

An example of humility from classical history is the Emperor Trajan, who, according to a medieval legend, once stopped his journey to render justice to a poor widow (Canto X).

Also associated with humility is an expanded version of the Lord's Prayer: "Our Father, You who dwell within the heavensbut are not circumscribed by them out ofYour greater love for Your first works above,Praised be Your name and Your omnipotence,by every creature, just as it is seemlyto offer thanks to Your sweet effluence.Your kingdom's peace come unto us, for ifit does not come, then though we summon allour force, we cannot reach it of our selves.Just as Your angels, as they sing Hosanna,offer their wills to You as sacrifice,so may men offer up their wills to You.Give unto us this day the daily mannawithout which he who labours most to moveahead through this harsh wilderness falls back.Even as we forgive all who have doneus injury, may You, benevolent,forgive, and do not judge us by our worth.Try not our strength, so easily subdued,against the ancient foe, but set it freefrom him who goads it to perversity".

The first of these souls is Omberto Aldobrandeschi, whose pride lies in his descent ("I was Italian, son of a great Tuscan: / my father was Guiglielmo Aldobrandesco"[38]), although he is learning to be more humble[39] ("I / do not know if you have heard his name"[40]).

In Canto XIII, Dante points out, with "frank self-awareness,"[41] that pride is also a serious flaw of his own: "I fear much more the punishment below;my soul is anxious, in suspense; alreadyI feel the heavy weights of the first terrace".

Dante compares the stairway to the easy ascent from the Rubiconte, a bridge in Florence, up to San Miniato al Monte, overlooking the city.

The former speaks bitterly about the ethics of people in towns along the River Arno: "That river starts its miserable courseamong foul hogs, more fit for acorns thanfor food devised to serve the needs of man.Then, as that stream descends, it comes on cursthat, though their force is feeble, snap and snarl;scornful of them, it swerves its snout away.And, downward, it flows on; and when that ditch,ill-fated and accursed, grows wider, itfinds, more and more, the dogs becoming wolves.Descending then through many dark ravines,it comes on foxes so full of deceitthere is no trap that they cannot defeat".

[57] The souls of the wrathful walk around in blinding acrid smoke, which symbolises the blinding effect of anger:[58] Darkness of Hell and of a night deprivedof every planet, under meager skies,as overcast by clouds as sky can be,had never served to veil my eyes so thicklynor covered them with such rough-textured stuffas smoke that wrapped us there in Purgatory;my eyes could not endure remaining open ...[59] The prayer for this terrace is the Agnus Dei: Agnus Dei, qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis ... dona nobis pacem ("Lamb of God, you who take away the sins of the world, have mercy upon us ... grant us peace").

Marco Lombardo discourses with Dante on free will – a relevant topic, since there is no point being angry with someone who has no choice over his actions[58] (Canto XVI).

Again the brightness overpowers Dante's sight, but he hears the angel's invitation to mount to the next terrace and feels a wing brush his forehead, erasing the third "P".

The three terraces they have seen so far have purged the proud ("he who, through abasement of another, / hopes for supremacy"),[62] the envious ("one who, when he is outdone, / fears his own loss of fame, power, honour, favour; / his sadness loves misfortune for his neighbor".

Allegorically, spiritual laziness and lack of caring lead to sadness,[67] and so the beatitude for this terrace is Beati qui lugent ("Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted," Matthew 5:4)[68] (Canto XVIII and XIX).

Upon awakening from the dream in the light of the sun, Dante is visited by the Angel of Zeal, who removes another "P" from his brow, and the two poets climb toward the fifth terrace[70] (Canto XIX).

Dante meets the shade of Pope Adrian V, an exemplar of desire for ecclesiastical power and prestige, who directs the poets on their way (Canto XIX).

Following the exemplars of avarice (these are Pygmalion, Midas, Achan, Ananias and Sapphira, Heliodorus, Polymestor, and Crassus), there is a sudden earthquake accompanied by the shouting of Gloria in excelsis Deo.

The Virgin Mary, who shared her Son's gifts with others at the Wedding at Cana, and John the Baptist, who only lived on locusts and honey (Matthew 3:4[79]), is an example of the virtue of temperance.

Bonagiunta has kind words for Dante's earlier work La Vita Nuova, describing its technique as the dolce stil novo ("sweet new style").

Showing the passage up the mountain, the angel removes another "P" from Dante's brow with a puff of his wing, and he pronounces the beatitude in paraphrase: "Blessed are they who are so illumined by grace that the love of food does not kindle their desires beyond what is fitting" (Canto XXIV).

[87] In addition, this depiction is a marked massive departure from Inferno, where Dante represents sodomy as a sin of violence instead of one of excessive love.

[93] Dante awakens with the dawn,[94] and the poets continue up the rest of the ascent until they come in sight of the Earthly Paradise (Canto XXVII).

This allegory includes a denunciation of the corrupt papacy of the time: a harlot (the papacy) is dragged away with the chariot (the Church) by a giant (the French monarchy, which under King Philip IV engineered the move of the Papal Seat to Avignon in 1309)[118] (Canto XXXII): Just like a fortress set on a steep slope,securely seated there, ungirt, a whore,whose eyes were quick to rove, appeared to me;and I saw at her side, erect, a giant,who seemed to serve as her custodian;and they again, again embraced each other.

[124] In the Renaissance, Antonio Manetti and Alessandro Vellutello proposed models which Galileo Galilei refuted in his On the Shape, Location, and Size of Dante's Inferno.