Purgatory

Purgatory (Latin: purgatorium, borrowed into English via Anglo-Norman and Old French)[1] is a passing intermediate state after physical death for purifying or purging a soul.

[2] In Catholic doctrine, purgatory refers to the final cleansing of those who died in the State of Grace, and leaves in them only "the holiness necessary to enter the joy of heaven";[3] it is entirely different from the punishment of the damned and is not related to the forgiveness of sins for salvation.

A forgiven person can be freed from his "unhealthy attachment to creatures" by fervent charity in this world, and otherwise by the non-vindictive "temporal (i.e. non-eternal) punishment" of purgatory.

[4] The New American Bible Revised Edition, authorized by the United States Catholic bishops, says in a note to the 2 Maccabees passage: "This is the earliest statement of the doctrine that prayers and sacrifices for the dead are efficacious.

Protestants usually do not recognize purgatory as such: following their doctrine of sola scriptura, they claim Jesus is not recorded mentioning or otherwise endorsing it, and the deuterocanonical book 2 Maccabees is not accepted by them as scripture.

[40] Unless "redeemed by repentance and God's forgiveness", mortal sin, whose object is grave matter and is also committed with full knowledge and deliberate consent, "causes exclusion from Christ's kingdom and the eternal death of hell, for our freedom has the power to make choices for ever, with no turning back.

[42] Venial sin, while not depriving the sinner of friendship with God or the eternal happiness of heaven,[43] "weakens charity, manifests a disordered affection for created goods, and impedes the soul's progress in the exercise of the virtues and the practice of the moral good; it merits temporal punishment",[43] for "every sin, even venial, entails an unhealthy attachment to creatures, which must be purified either here on earth, or after death in the state called purgatory.

"[42]Joseph Ratzinger has paraphrased this as: "Purgatory is not, as Tertullian thought, some kind of supra-worldly concentration camp where man is forced to undergo punishment in a more or less arbitrary fashion.

[46] The Catholic Church states that, through the granting of indulgences for manifestations of devotion, penance and charity by the living, it opens for individuals "the treasury of the merits of Christ and the saints to obtain from the Father of mercies the remission of the temporal punishments due for their sins".

On the cusp of the Reformation, St Catherine of Genoa (1447–1510) re-framed the theology of purgatory as voluntary, loving and even joyful: "As for paradise, God has placed no doors there.

[50]In his 2007 encyclical Spe salvi, Pope Benedict XVI teaches:[50] It is clear that we cannot calculate the 'duration' of this transforming burning in terms of the chronological measurements of this world.

[citation needed] The representatives of the Eastern Orthodox Church at the Council of Florence (1431–1449) argued against these notions, while declaring that they do hold that there is a cleansing after death of the souls of the saved and that these are assisted by the prayers of the living: "If souls depart from this life in faith and charity but marked with some defilements, whether unrepented minor ones or major ones repented of but without having yet borne the fruits of repentance, we believe that within reason they are purified of those faults, but not by some purifying fire and particular punishments in some place.

Le Goff dedicates the final chapter of his book to the Purgatorio, the second canticle of the Divine Comedy, a poem by fourteenth-century Italian author Dante Alighieri.

In an interview Le Goff declared: "Dante's Purgatorio represents the sublime conclusion of the slow development of Purgatory that took place in the course of the Middle Ages.

"[58] Dante pictures Purgatory as an island at the antipodes of Jerusalem, pushed up, in an otherwise empty sea, by the displacement caused by the fall of Satan, which left him fixed at the central point of the globe of the Earth.

"[69]Gregory the Great also argued for the existence, before Judgment, of a purgatorius ignis (a cleansing fire) to purge away minor faults (wood, hay, stubble) not mortal sins (iron, bronze, lead).

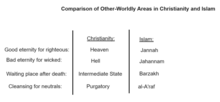

[75][76] While the Eastern Orthodox Church rejects the term Purgatory, it acknowledges an intermediate state after death and before final judgment, and offers prayer for the dead.

[77]Eastern Orthodox teaching is that, while all undergo an individual judgment immediately after death, neither the just nor the wicked attain the final state of bliss or punishment before the Last Day,[78] with some exceptions for righteous souls like the Theotokos (Blessed Virgin Mary), "who was borne by the angels directly to heaven.

According to this theory, which is rejected by other Orthodox but appears in the hymnology of the church,[85] "following a person's death the soul leaves the body and is escorted to God by angels.

"[86] Some early patristic theologians of the Eastern Church taught and believed in "apocatastasis", the belief that all creation would be restored to its original perfect condition after a remedial purgatorial reformation.

[90][91] Reformed Protestants, consistent with the views of John Calvin, hold that a person enters into the fullness of one's bliss or torment only after the resurrection of the body, and that the soul in that interim state is conscious and aware of the fate in store for it.

[89] The Protestant Reformer Martin Luther was once recorded as saying:[98]As for purgatory, no place in Scripture makes mention thereof, neither must we any way allow it; for it darkens and undervalues the grace, benefits, and merits of our blessed, sweet Saviour Christ Jesus.

Neither do we favor Aerius, but we do argue with you because you defend a heresy that clearly conflicts with the prophets, apostles, and Holy Fathers, namely, that the Mass justifies ex opere operato, that it merits the remission of guilt and punishment even for the unjust, to whom it is applied, if they do not present an obstacle."

[111] Shortly before becoming a Roman Catholic,[112] John Henry Newman argued that the essence of the doctrine is locatable in ancient tradition, and that the core consistency of such beliefs is evidence that Christianity was "originally given to us from heaven".

[114] Lewis's allegory The Great Divorce (1945) considered a version of purgatory in the related idea of a "refrigidarium", the opportunity for souls to visit a lower region of heaven and choose to be saved, or not.

"[117] However, in traditional Methodism, there is a belief in Hades, "the intermediate state of souls between death and the general resurrection," which is divided into Paradise (for the righteous) and Gehenna (for the wicked).

He believes the sanctification model "can be affirmed by Protestants without in any way contradicting their theology" and that they may find that it "makes better sense of how the remains of sin are purged" than an instantaneous cleansing at the moment of death.

Regarding the time which Purgatory lasts, the accepted opinion of R. Akiba is twelve months; according to R. Johanan b. Nuri, it is only forty-nine days.

[135] Maimonides declares, in his 13 principles of faith, that the descriptions of Gehenna, as a place of punishment in rabbinic literature, were pedagocically motivated inventions to encourage respect of the Torah commandments by mankind, which had been regarded as immature.

One of these, discussed in the Mahābhārata, holds that one goes from naraka's punishment straight to heaven (svarga) in their next life, though this celestial realm is distinct from the ultimate form of salvation in Hinduism: spiritual liberation from the cycle of rebirth known as mokṣa.