Pyramid of Unas

The causeway had elaborately decorated walls covered with a roof which had a slit in one section allowing light to enter, illuminating the images.

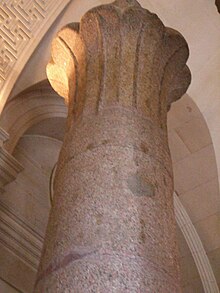

The mortuary temple was entered on its east side through a large granite doorway, seemingly constructed by Unas's successor, Teti.

The underground chambers remained unexplored until 1881, when Gaston Maspero, who had recently discovered inscribed texts in the pyramids of Pepi I and Merenre I, gained entry.

In Unas's case, the funerary cult may have survived the turbulent First Intermediate Period and up until the Twelfth or Thirteenth Dynasty, during the Middle Kingdom.

[4] From 1899 to 1901, the architect and Egyptologist Alessandro Barsanti conducted the first systematic investigation of the pyramid site, succeeding in excavating part of the mortuary temple, as well as a series of tombs from the Second Dynasty and the Late Period.

The archaeologists Selim Hassan, Muhammed Zakaria Goneim and A. H. Hussein mainly focused on the causeway leading to the pyramid while conducting their investigations from 1937 to 1949.

[23] The pyramids of Unas, Teti, Pepi I and Merenre were the subjects of a major architectural and epigraphic project in Saqqara, led by Jean Leclant.

[49] From the vestibule, a 14.10 m (46.3 ft) long horizontal passage follows a level path to the antechamber and is guarded by three granite slab portcullises in succession.

[27] Near the burial chamber's west wall sat Unas's coffin, made from greywacke rather than basalt as was originally presumed.

[27] Traces of the burial are fragmentary; all that remain are portions of a mummy, including its right arm, skull and shinbone, as well as the wooden handles of two knives used during the opening of the mouth ceremony.

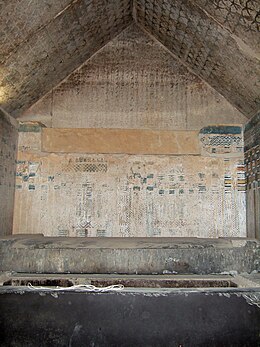

[36] The walls of the chambers were lined with Tura limestone,[60] while those surrounding Unas's sarcophagus[36][61] were sheathed in white alabaster incised and painted to represent the doors of the royal palace facade, complementing the eastern passage.

[63] The walls appear to contain blocks reused from one of Khufu's constructions, possibly his pyramid complex at Giza, as an earlier scene of the king (identified by his Horus name Medjedu) fishing with a harpoon was discovered beneath those carved for Unas.

[27] The remaining walls of the burial chamber, antechamber, and parts of the corridor were inscribed with a series of vertically written texts, chiselled in bas-relief and painted blue.

[73][75] The function of the texts, in congruence with all funerary literature, was to enable the reunion of the ruler's ba and ka leading to the transformation into an akh,[81][79] and to secure eternal life among the gods in the sky.

[91] The Egyptologist James Allen identifies the last piece of ritual text on the west gable of the antechamber:[86] Your son Horus has acted for you.

[67] The west, north and south walls of the antechamber contain texts whose primary concern is the transition from the human realm to the next, and with the king's ascent to the sky.

[111] Construction of the causeway was complicated and required negotiating uneven terrain and older buildings which were torn down and their stones appropriated as underlay.

[5] The remnants depict a variety of scenes including the hunting of wild animals, the conducting of harvests, scenes from the markets, craftsmen working copper and gold, a fleet returning from Byblos, boats transporting columns from Aswan to the construction site, battles with enemies and nomadic tribes, the transport of prisoners, lines of people bearing offerings, and a procession of representatives from the nomes of Egypt.

[5][29][117] A slit was left in a section of the causeway roofing, allowing light to enter illuminating the brightly painted decorations on the walls.

The scene had been used as "unique proof" that the living standards of desert dwellers had declined during Unas's reign as a result of climatic changes in the middle of the third millennium B.C.

Verner contends that the nomads may have been brought in to demonstrate the hardships faced by pyramid builders bringing in higher quality stone from remote mountain areas.

[29] Grimal suggested that this scene foreshadowed the nationwide famine that seems to have struck Egypt[g] at the onset of the First Intermediate Period.

[119] According to Allen et al., the most widely accepted explanation for the scene is that it was meant to illustrate the generosity of the sovereign in aiding famished populations.

[125] Ahmed Moussa discovered the rock-cut tombs of Nefer and Ka-hay – court singers during Menkauhor's reign[127] – south of Unas's causeway, containing nine burials along with an extremely well preserved mummy found in a coffin in a shaft under the east wall of the chapel.

[128] The Chief Inspector at Saqqara, Mounir Basta, discovered another rock-cut tomb just south of the causeway in 1964, later excavated by Ahmed Moussa.

The tombs belonged to two palace officials – manicurists[129] – living during the reigns of Nyuserre Ini and Menkauhor, in the Fifth Dynasty, named Ni-ankh-khnum and Khnum-hotep.

[143][5] Remnants of a granite false door bearing an inscription concerning the souls of the residents of Nekhen and Buto marks what little of the offering hall has been preserved.

[155] The Egyptologist Jaromír Málek contends that the evidence only suggests a theoretical revival of the cult, a result of the valley temple serving as a useful entry path into the Saqqara necropolis, but not its persistence from the Old Kingdom.

In the Nineteenth Dynasty,[20] Khaemweset, High Priest of Memphis and son of Ramesses II, had an inscription carved onto a block on the pyramid's south side commemorating his restoration work.

[5][27] Late Period monuments, colloquially called the "Persian tombs", thought to date to the reign of Amasis II, were discovered near the causeway.

Materials colour-coded: light orange = fine white limestone; red = red granite; white = white alabaster; grey = greywacke.