Construction of the Egyptian pyramids

The construction of the Egyptian pyramids can be explained with well-established scientific facts, however there are some aspects that are even today considered controversial hypotheses.

Diodorus Siculus's account states:[5] And it's said the stone was transported a great distance from Arabia, and that the edifices were raised utilizing earthen ramps since machines for lifting had not yet been invented in those days; and most surprising it is, that although such large structures were raised in an area surrounded by sand, no trace remains of either ramps or the dressing of the stones, so that it seems not the result of the patient labour of men, but rather as if the whole complex were set down entire upon the surrounding sand by some god.

Now Egyptians try to make a marvel of these things, alleging that the ramps were made of salt and natron and that, when the river was turned against them, it melted them clean away and obliterated their every trace without the use of human labour.

Rather, the same multitude of workmen who raised the mounds returned the entire mass to its original place; for they say that three hundred and sixty thousand men were constantly employed in the prosecution of their work, yet the entire edifice was hardly finished at the end of twenty years.Diodorus Siculus's description of the shipment of the stone from Arabia is correct since the term "Arabia" in those days implied the land between the Nile and the Red Sea[6] where the limestone blocks have been transported from quarries across the river Nile.

Granite, quarried near Aswan, was used to construct some architectural elements, including the portcullis (a type of gate) and the roofs and walls of the burial chamber.

As suggested by team members, "We thought that it was unlikely that the pyramid builders consistently used centuries-old wood as fuel in preparing mortar.

The harder stones, such as granite, granodiorite, syenite, and basalt, cannot be cut with copper tools alone; instead, they were worked with time-consuming methods like pounding with dolerite, drilling, and sawing with the aid of an abrasive, such as quartz sand.

The diary of Merer, logbooks written more than 4,500 years ago by an Egyptian official and found in 2013 by a French archeology team under the direction of Pierre Tallet in a cave in Wadi al-Jarf, describes the transportation of limestone blocks from the quarries at Tura to Giza by boat.

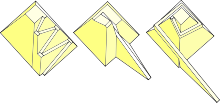

Mark Lehner speculated that a spiraling ramp, beginning in the stone quarry to the southeast and continuing around the exterior of the pyramid, may have been used.

The challenge was the geometry of the pyramid that provides shorter side lengths the higher the building grows, increases the necessity to turn maneuvers and allows less space for ramps leaning on the masonry.

In other words, in Lehner's view, levers should be employed to lift a small amount of material and a great deal of vertical height of the monument.

Since the discussion of construction techniques to lift the blocks attempts to resolve a gap in the archaeological and historical record with a plausible functional explanation, the following examples by Isler, Keable, and Hussey-Pailos[28] list experimentally tested methods.

A 2012 study led by geographer Hader Sheisha at Aix-Marseille University proposed that the former waterscapes and higher river levels around 4,500 years ago facilitated the construction of the Giza Pyramid Complex.

Using satellite imaging and sediment core analysis, researchers found the 64 kilometres (40 mi) waterway was crucial for transporting materials and labor for pyramid construction.

They suggested that The Ahramat Branch played a role in the monuments’ construction and that it was used to transport workmen and building materials to the pyramids’ sites.

[32] It has been suggested that locks were used to elevate barges along waterways leading to pyramid construction sites, but there is a lack of evidence of any on-site use of hydraulic force.

[34] In 1992,[citation needed] Egyptologist Mark Lehner and stonemason Roger Hopkins conducted a three-week pyramid-building experiment for a Nova television episode.

They used iron hammers, chisels and levers (this is a modern shortcut, as the ancient Egyptians were limited to using copper and later bronze and wood).

While the builders failed to duplicate the precise jointing created by the ancient Egyptians, Hopkins was confident that this could have been achieved with more practice.

For instance, physicist Kurt Mendelssohn calculated that the workforce may have been 50,000 men at most, while Ludwig Borchardt and Louis Croon placed the number at 36,000.

[citation needed] Evidence suggests that around 5,000 were permanent workers on salaries with the balance working three- or four-month shifts in lieu of taxes while receiving subsistence "wages" of ten loaves of bread and a jug of beer per day.

Without the use of pulleys, wheels, or iron tools, they used critical path analysis to suggest the Great Pyramid was completed from start to finish in approximately 10 years.

[38] As Dr. Craig Smith of the team points out: The logistics of construction at the Giza site are staggering when you think that the ancient Egyptians had no pulleys, no wheels, and no iron tools.

This does not include Khafre's brother Djedefre's northern pyramid at Abu Rawash, which would have also been built during this time frame of 100 years.

[41] In October 2018, a team of archaeologists from the Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale and University of Liverpool announced the discovery of the remains of a 4,500-year-old ramp contraption at Hatnub, excavated since 2012.

[42] Yannis Gourdon, co-director of the joint mission at Hatnub, said:[42] This system is composed of a central ramp flanked by two staircases with numerous post holes, using a sled which carried a stone block and was attached with ropes to these wooden posts, ancient Egyptians were able to pull up the alabaster blocks out of the quarry on very steep slopes of 20 percent or more ... As this system dates back at least to Khufu's reign, that means that during the time of Khufu, ancient Egyptians knew how to move huge blocks of stone using very steep slopes.

To develop this hypothesis, Jean-Pierre Houdin, also an architect, gave up his job and set about drawing the first fully functional CAD architectural model of the Great Pyramid of Giza.

[47] This 10-square-meter clear space housed a crane that lifted and rotated each 2.5-ton block, to ready it for eight men to drag up the next internal ramp.

There is a notch of sorts in one of the right places, and in 2008 Houdin's co-author Bob Brier, with a National Geographic film crew, entered a previously unremarked chamber that could be the start of one of these internal ramps.

[49] Houdin has another hypothesis developed from his architectural model, one that could finally explain the internal "Grand Gallery" chamber that otherwise appears to have little purpose.