Pyramid of Userkaf

Constructed in dressed stone with a core of rubble, the pyramid is now ruined and resembles a conical hill in the sands of Saqqara.

[1] For this reason, it is known locally as El-Haram el-Maharbish, the "Heap of Stone",[2] and was recognized as a royal pyramid by western archaeologists in the 19th century.

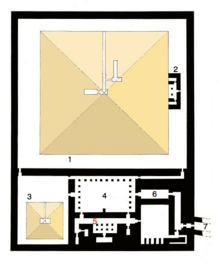

[4] The complex is markedly different from those built during the 4th Dynasty (c. 2613–2494 BC) in its size, architecture and location, being at Saqqara rather than the Giza Plateau.

During the first season of excavation, Firth and Lauer cleared the south side of the pyramid area, discovering Userkaf's mortuary temple and tombs of the much later Saite period.

[7] The following year, Firth and Lauer uncovered a limestone relief slab and a colossal red granite head of Userkaf, thus determining that he was the pyramid owner.

Research on the north and west sides of the mortuary complex was conducted starting in 1976 by Ahmed el-Khouli[1][4][8][9] who excavated and restored the pyramid entrance.

Finally, immediately to the south of Userkaf's funerary enclosure is a second smaller pyramid complex attributed to his wife, queen Neferhetepes.

[3] The reason for these changes is unclear, and several hypotheses have been proposed to explain them: Userkaf's mortuary temple layout and architecture is difficult to establish with certainty.

Not only was it extensively quarried for stone throughout the millennia, but a large Saite period shaft tomb was also dug in its midst,[7] damaging it.

[1] That in turn led to an open black-basalt floored courtyard bordered on all sides but the south one by monolithic red granite pillars bearing the titles of the king.

[12] The walls of the courtyard were adorned with fine reliefs of high workmanship depicting scenes of life in a papyrus thicket, a boat with its crew and names of Upper and Lower Egyptian estates connected to the cult of the king.

Two doors at the south-east and south-west corners of the courtyard led to a small hypostyle hall with four pairs of red granite pillars.

The only remains of the mortuary temple that are visible today are its basalt paving and the large granite blocks framing the outer door.

This difference is certainly linked with the peculiar overall north–south layout of Userkaf's complex with the south-eastern corner hosting the entrance to the mortuary temple.

The entrance was hewn into the bedrock and floored and roofed with large slabs of white limestone, most of which have been removed in modern times.

[6] Behind the granite barrier the corridor branches eastward to a T-shaped magazine chamber which probably contained Userkaf's funerary equipment.

At the western end of the burial chamber Perring discovered some fragments of an empty and undecorated black basalt sarcophagus which had been originally placed in a slight depression as well as a canopic chest.

Thus 10 metres (33 ft) to the south of his funerary enclosure, Userkaf had a small separate pyramid complex built for his queen on an east–west axis.

His tomb is located in the immediate vicinity of Userkaf's complex and yielded an inscribed stone giving the name and rank of the queen.

In fact, the pyramid was so extensively used as a stone quarry in later times that it is now barely distinguishable from the surroundings and its internal chambers are exposed.

From the ruins, archaeologists propose that the temple comprised an open colonnade, possibly made of granite,[3] a sacrificial chapel adjoining the pyramid side, three statue niches and a few magazine chambers.

[3] The pyramid of Userkaf was apparently the object of restoration work in antiquity under the impulse of Khaemweset (1280–1225 BC), fourth son of Ramesses II.

[17] During the 26th Dynasty (c. 685-525 BC) Userkaf's temple had become a burial ground: a large shaft tomb was dug in its midst thus rendering modern reconstruction of its layout difficult.