Pyroelectricity

If the temperature stays constant at its new value, the pyroelectric voltage gradually disappears due to leakage current.

Under normal circumstances, even polar materials do not display a net dipole moment.

Polar crystals only reveal their nature when perturbed in some fashion that momentarily upsets the balance with the compensating surface charge.

The first record of the pyroelectric effect was made in 1707 by Johann Georg Schmidt, who noted that the "[hot] tourmaline could attract the ashes from the warm or burning coals, as the magnet does iron, but also repelling them again [after the contact]".

[8] In 1717 Louis Lemery noticed, as Schmidt had, that small scraps of non-conducting material were first attracted to tourmaline, but then repelled by it once they contacted the stone.

[12] Both William Thomson in 1878[13] and Woldemar Voigt in 1897[14] helped develop a theory for the processes behind pyroelectricity.

The misconception arose soon after the discovery of the pyroelectric properties of tourmaline, which made mineralogists of the time associate the legendary stone Lyngurium with it.

However, the positive and negative charges which make up the material are not necessarily distributed in a symmetric manner.

The piezoelectric effect is exhibited by crystals (such as quartz or ceramic) for which an electric voltage across the material appears when pressure is applied.

Similar to pyroelectric effect, the phenomenon is due to the asymmetric structure of the crystals that allows ions to move more easily along one axis than the others.

Although artificial pyroelectric materials have been engineered, the effect was first discovered in minerals such as tourmaline.

[19] The large electric fields in this material are detrimental in light emitting diodes (LEDs), but useful for the production of power transistors.

[citation needed] Progress has been made in creating artificial pyroelectric materials, usually in the form of a thin film, using gallium nitride (GaN), caesium nitrate (CsNO3), polyvinyl fluorides, derivatives of phenylpyridine, and cobalt phthalocyanine.

[20] Recently, pyroelectric and piezoelectric properties have been discovered in doped hafnium oxide (HfO2), which is a standard material in CMOS manufacturing.

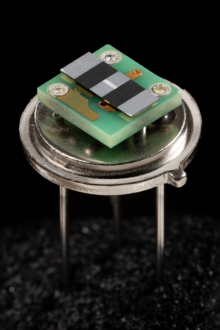

Passive infrared sensors are often designed around pyroelectric materials, as the heat of a human or animal from several feet away is enough to generate a voltage.

Pyroelectric materials have been used to generate large electric fields necessary to steer deuterium ions in a nuclear fusion process.