Pythagorean hammers

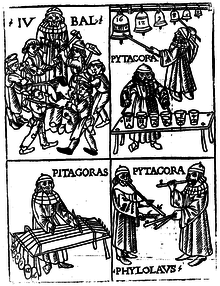

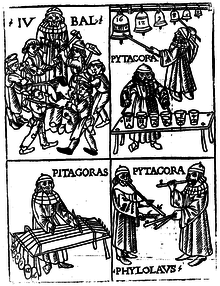

According to legend, Pythagoras discovered the foundations of musical tuning by listening to the sounds of four blacksmith's hammers, which produced consonance and dissonance when they were struck simultaneously.

"[6] Whatever the details of the discovery of the relationship between music and ratio, it is regarded[7] as historically the first empirically secure mathematical description of a physical fact.

As he passed by a forge where four (according to a later version, five) craftsmen were working with hammers, he noticed that each strike produced tones of different pitch, which resulted in harmonies when paired.

With the invention of the monochord to investigate and demonstrate the harmonies of pairs of strings with different integer length ratios, Pythagoras is said to have introduced a convenient means of illustrating the mathematical foundation of music theory that he discovered.

The device is equipped with a movable bridge, which allows the vibrating length of the string to be divided; the division can be precisely determined using the measurement scale.

Walter Burkert dates this achievement to a time after the era of Aristotle, who apparently did not know the device; thus, it was introduced long after Pythagoras' death.

[12] On the other hand, Leonid Zhmud suggests that Pythagoras probably conducted his experiment, which led to the discovery of numerical ratios, using the monochord.

[14] Walter Burkert is of the opinion that despite its physical impossibility, the legend should not be regarded as an arbitrary invention, but rather as having a meaning that can be found in Greek mythology.

With the advent of polyphony in the second half of the 15th century, in addition to the octave and fifth, the pure third became crucial for major and minor triads.

Bodies with more complex geometry, such as bells, cups, or bowls, which may even be filled with liquids, have natural frequencies that require considerably more elaborate physical descriptions since not only the shape but also the wall thickness or even the striking location must be considered.

It is possible to compare metal rods, such as chisels used by stonemasons or splitting wedges for stone breaking, in order to arrive at an observation similar to the one attributed to Pythagoras, namely that the vibration frequency of tools is proportional to their weight.

The earliest mention of Pythagoras' discovery of the mathematical basis of musical intervals is found in the Platonist Xenocrates (4th century BC); as it is only a quote from a lost work of this thinker, it is unclear whether he knew the forge legend.

[23] In the 4th century BC, criticism of the Pythagorean theory of intervals was already expressed, although without reference to the Pythagoras legend; the philosopher and music theorist Aristoxenus considered it to be false.

[24] The famous mathematician and music theorist Ptolemy (2nd century AD) was aware of the weight method transmitted by the legend but rejected it.

[26] The chronologically difficult to place music theorist of the Imperial era, Gaudentius, described the legend in his Harmonikḗ Eisagōgḗ ("Introduction to Harmony"), in a version slightly shorter than that of Nicomachus.

The Neoplatonist philosopher Iamblichus of Chalcis, who worked as a philosophy teacher in the late 3rd and early 4th centuries, wrote a Pythagoras biography titled On the Pythagorean Life, in which he reproduced the blacksmith legend in the version of Nicomachus.

In the first half of the 5th century, the writer Macrobius extensively discussed the blacksmith legend in his commentary on Cicero's Somnium Scipionis, which he described in a similar manner to Nikomachos.

The path to knowledge went from sensory perception to the initial hypothesis, which turned out to be erroneous, then to the formation of a correct opinion, and finally to its verification.

[29] In the 6th century, the scholar Cassiodorus wrote in his Institutiones that Gaudentius attributed the beginnings "of music" to Pythagoras in his account of the legend of the blacksmith.

[31] As Cassiodorus and Isidore were first-rate authorities in the Middle Ages, the notion spread that Pythagoras had discovered the fundamental law of music and thus had been its founder.

[34] In the first half of the 11th century, Guido of Arezzo, the most famous music theorist of the Middle Ages, recounted the legend of the blacksmith in the final chapter of his Micrologus, basing it on the version of Boethius, whom he named specifically.

As an opponent of the Pythagorean conception, which held that consonances were based on certain numerical ratios, Johannes de Grocheio emerged in the 13th century, starting from an Aristotelian perspective.

Although he explicitly stated that Pythagoras had discovered the principles of music, and he told the legend of the forge citing Boethius, whom he considered trustworthy, he rejected the Pythagorean theory of consonance, which he wanted to reduce to a merely metaphorical expression.

These numbers correspond, for example, to the tones f – c' – f' – g' – c" – f": The painter Erhard Sanßdorffer was commissioned in 1546 to create a fresco in the Hessian Büdingen Castle, which is well preserved and represents the history of music starting from the forge of Pythagoras like a compendium.

[38] Gioseffo Zarlino also recounted the legend in his work Le istitutioni harmoniche ("The Foundations of Harmony"), which he published in 1558; like Gaffurio, he based his account on Boethius' version.

[1] In 1626, the Thesaurus philopoliticus by Daniel Meisner featured a copper engraving titled "Duynkirchen" by Eberhard Kieser, depicting only three blacksmiths at an anvil.

The Latin and German caption reads:[2] A few years later, the matter was definitively clarified after Galileo Galilei and Marin Mersenne discovered the laws of string vibrations.

In 1636, Mersenne published his Harmonie universelle, in which he explained the physical error in the legend: the vibration frequency is not proportional to the tension, but to its square root.

[41] Even in the 19th century, Hegel assumed the physical accuracy of the alleged measurements mentioned in the Pythagoras legend in his lectures on the history of philosophy.

[42] Werner Heisenberg emphasized in an essay first published in 1937 that the Pythagorean "discovery of the mathematical determinacy of harmony" is based on "the idea of the meaningful power of mathematical structures", a "fundamental idea that modern exact science has inherited from antiquity"; the discovery attributed to Pythagoras belongs "to the strongest impulses of human science in general".

Sound examples of chisels with vibration frequencies that are in integer ratios to each other: