Jiang Qing

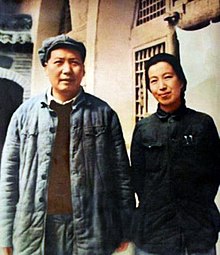

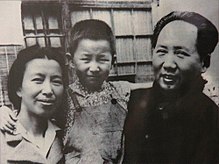

Born into a declining family with an abusive father and a mother who worked as a domestic servant and sometimes a prostitute, Jiang Qing became a renowned actress in Shanghai, and later the wife of Mao Zedong in Yan'an, in the 1930s.

State media portrayed her as the "White-Boned Demon," and she was widely blamed for instigating the Cultural Revolution, a period of upheaval that caused the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Chinese people.

The Marco Polo Bridge Incident in July 1937, which marked the start of Japan's full-scale invasion of China, further galvanised young activists to advocate for a united front.

The Lu Xun Academy of Arts was newly founded in Yan'an on 10 April 1938, and Jiang became a drama department instructor, teaching and performing in college plays and operas.

During their conversation, Jiang even asked Soong to encourage Mao to wear a tie and suits, noting that Sun Yat-sen often did so and suggesting that foreigners found the simplicity of Chinese officials' clothing too monotonous.

People close to Mao Zedong claimed that after the 1950s, Jiang Qing was rarely seen by his side, and their emotional relationship had essentially ended, leaving her feeling frustrated for a time.

Their shared vision focused on creating operas that reflected modern Chinese society and the lives of the working class, starting with On the Docks, which portrayed Communist-ruled Shanghai.

[47] From 1962 onwards, Jiang Qing began appearing publicly as Mao's wife and later gave frequent speeches in the cultural and propaganda sectors, criticizing and condemning various figures.

He proposed moving with his wife and children to Yan’an or his hometown in Hunan to take up farming, hoping to bring the Cultural Revolution to an early conclusion and minimise the damage to the country.

On 18 December, Zhang Chunqiao, deputy head of the Central Cultural Revolution Group, summoned Kuai Dafu, a leader of the Red Guards at Tsinghua University, and instructed him to launch a campaign to overthrow Liu Shaoqi.

On 25 December, Kuai Dafu led thousands of demonstrators in Tiananmen Square, where they publicly chanted the slogan “Down with Liu Shaoqi.”[70] The Central Cultural Revolution Group was initially a small body under the Standing Committee of the Politburo.

[54] With the backing of Jiang Qing, Zhang Chunqiao and Yao Wenyuan initiated a coup in Shanghai in January 1967, consolidating power and gaining support from revolutionary factions like Wang Hongwen.

On 16 September 1968, under Jiang Qing’s leadership, a special investigation team compiled three volumes of so-called evidence against Liu, largely extracted through torture and coercion.

At the 9th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in April 1969, Jiang was admitted to the Politburo after Mao Zedong shifted his stance, likely to balance the power of the Lin Biao faction.

[74] After the September 13 Incident in 1971, Jiang Qing saw the collapse of the Lin Biao faction and, with Mao Zedong's declining health, she became eager to seize the highest power in the country.

This revelation deeply angered Mao, who, in a fit of rage, even expressed his desire to expel Jiang Qing from the Politburo and sever their political ties.

[75] After Zhou Enlai was hospitalised, Wang Hongwen managed the Politburo, Deng Xiaoping oversaw the State Council, and Ye Jianying led the Central Military Commission.

[80] On the evening of 8 September, she drove to Xinhua News Agency trying to find supporters, and returned to Zhongnanhai late in night, where high-rank Chinese officials and Mao's family members were present.

[89] She was accused of persecuting artists during the Cultural Revolution, and authorising the burgling of the homes of writers and performers in Shanghai to destroy material related to Jiang's early career that could harm her reputation.

[89] Following her arrest, Jiang Qing was held at Qincheng Prison, where she occupied herself with activities such as reading newspapers, listening to radio broadcasts, watching television, knitting, studying books, and writing.

[84] The Supreme People's Court determined that both Jiang and her chief associate, Zhang, had demonstrated "sufficient repentance" during their two-year reprieve, leading to their death sentences being commuted.

However, senior Chinese officials stated that Jiang has not shown genuine remorse and remains as defiant as the day she was removed from a crowded courtroom, shouting, "Long Live the Revolution.

[79] Jiang Qing is often viewed as a figure of naked ambition, with many perceiving her as a typical power-hungry wife of an emperor, seeking to secure power for herself through questionable means.

Jiang herself became the primary target of ridicule, portrayed as an empress scheming to succeed Mao and as a prostitute, with references to her past as a Shanghai actress used to question her moral integrity.

The indictment held the Gang responsible for the violence of the Cultural Revolution, accusing Jiang of using political purges for personal vendettas and fostering large-scale chaos.

Widely broadcast both within and outside China, the trial reinforced a clear dichotomy: Jiang as a symbol of the past’s chaos, and Deng Xiaoping’s administration as the harbinger of order and progress.

While factual biographies aim to deliver an accurate portrayal of their subject, fictional works take creative liberties, reimagining the life of a historical figure without strict adherence to facts.

Frustrated Maoist supporters questioned why publicly honouring Chiang Kai-shek was permitted while commemorating Jiang Qing was not, rhetorically asking if the Republic of China had somehow reclaimed the mainland.

[111] Since 2021, as large numbers of visitors continued to honour Jiang Qing, international media noted that authorities allowed leftist groups to commemorate her while prohibiting public mourning for Zhao Ziyang.

[113] Jiang's hobbies included photography, playing cards, and holding screenings of classic Hollywood films, especially those featuring Greta Garbo, one of her favorite actresses, even as they were banned for the average Chinese citizen as a symbol of bourgeois decadence.