Government of the Inca Empire

Their worldview was animistic, and their amauta or amawt’a (teachers or sages) taught that the world was suffused with kamaq, meaning "breath" or "life-force".

Change was understood as occurring through asymmetries in power between those forces, while pacha, an equilibrium or balance, was struck through ayni, a process of reciprocal exchange.

Likewise, cults of the dead were very ancient in the Andes, and so the worship of deceased, mummified Incas attended to by their descendant panaqa groups was not revolutionary.

However, as Conrad and Demerest argue, the "simplification" of these beliefs and rituals, "stressing the solar aspects of the ancient divine complex" in the form of Inti as a patron deity of the empire during the reign of Pachacuti.

Local religious traditions were allowed to continue, and in some cases such as the Oracle at Pachacamac (Pacha Kamaq, "vivifier of the world") on the Peruvian coast, were officially venerated.

Following Pachacuti, the Sapa Inca claimed descent from Inti, which placed a high value on imperial blood; by the end of the empire, it was common to wed brother and sister.

Moreover, Cuzco itself was considered cosmologically central, loaded as it was with huacas and radiating ceque lines, and geographic center of the Four Quarters; Inca Garcilaso de la Vega himself called it "the navel of the universe.

"[5][6][7][8] Land was conceptualized as ultimately belonging to the Inca, and distributed between the three estates of the empire—the imperial church, the commoners, and the state itself—for their benefit and care according to the principle of reciprocity.

This old Andean practice performed two functions; first, as divine hostage holding to ensure loyalty; second, as a sign of piety on the part of Inca rulers.

The formal education in Cuzco of the children of noble families from recently acquired territories disseminated fluency in Quechua, imperial law, and bureaucratic practices.

The deceased king himself, or rather his mallki (mummy), was believed to continue to communicate with the living and so was involved in the affairs of state, be they political or ceremonial.

Through blood ties, ample estates with yanakuna (servants or retainers) providing labor, and the possession of totemic and deified mallki, a panaqa was able to wield considerable political power, having influence over the selection of future Sapa Incas.

These lower level governors administered the provinces with the assistance of michuq officers, khipu kamayuq record keepers, kuraka officials, and yanakuna retainers.

The primary functions of a toqrikoq were to maintain state infrastructure, organize the census, and mobilize labor or military resources when called upon.

Typically, these governors, be they apu or tuqrikuq, were ethnic Inca, but some provincial groups did manage to ascend to the lower level.

[24] [25] While the Inca state exacted taxes in kind—e.g., textiles, grain, wares, etc.—it also drew upon corvée labor as an important supply of power.

Despite moving perhaps hundreds of miles to new homes, mitmas were still considered members of their original, native group and land for census and mit'a purposes.

[28][29] Sapa Inka, the supreme ruler Apu, the Governor of a suyu Tuqrikuq, the Governor of a wamani Kuraka, hereditary bureaucratic officials Inkap Rantin, a viceroy Attendant yanakuna retainers Attendant yanakuna retainers Kamayuq, non-hereditary bureaucratic officials Willaq Umu, the High Priest of the Sun Michuq, assisting officers Mit’ayuq tax-payers Council of the Realm, consisting of: Khipu kamayuq, record keepers Tukuy rikuq, inspectors reporting to the Sapa Inca Chaski, messengers Mallki, royal mummies Apukuna, military Generals The Inca state had no separate judiciary or codified set of laws.

While customs, expectations, and traditional local power holders did much in the way of governing behavior, the state, too, had legal force, such as through tukuy rikuq (lit.

The sentencing of an individual to death rested only among the highest authorities: provincial governors, the apu of the four suyu, and the Sapa Inca himself.

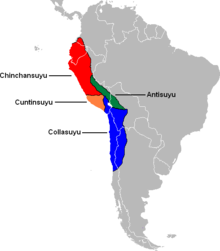

It is probably the case that at the time the suyu were established they were roughly of equal size and only later changing their proportions as the empire expanded north and south along the Andes.

Following the saya subdivision, the empire was subdivided into ayllu lineage groups, which were then again divided into upper hanan and lower hurin moieties, and then into individual family units.

This suyu encompassed the Bolivian Altiplano and much of the southern Andes, running down into Argentina and as far south as the Maule river near modern Santiago, Chile.