Aztec Empire

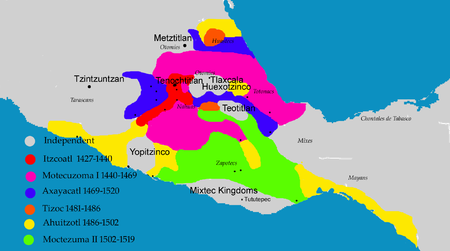

The alliance controlled most of central Mexico at its height, as well as some more distant territories within Mesoamerica, such as the Xoconochco province, an Aztec exclave near the present-day Guatemalan border.

In return, the imperial authority offered protection and political stability and facilitated an integrated economic network of diverse lands and peoples who had significant local autonomy.

Peoples were allowed to retain and freely continue their own religious traditions in conquered provinces so long as they added the imperial god Huītzilōpōchtli to their local pantheons.

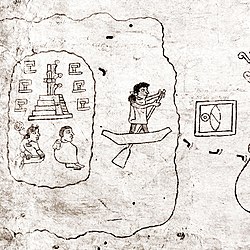

[10] The migration story of the Mexica is similar to those of other polities in central Mexico, with supernatural sites, individuals, and events, joining earthly and divine history, as they sought political legitimacy.

[14] The Mexica persuaded the king of Culhuacan, a small city-state but important historically as a refuge of the Toltecs to make them settle in a relatively infertile patch of land called Chapultepec (Chapoltepēc, "in the hill of grasshoppers").

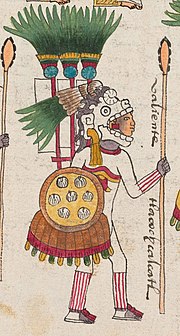

The importance of warriors and the integral nature of warfare in Mexica political and religious life helped propel them to emerge as the dominant military power in the region.

[18] The Tepanecs of Azcapotzalco expanded their rule with help from the Mexica, while the Acolhua city of Texcoco grew in power in the eastern portion of the lake basin.

Nezahualcoyotl recruited military help from the king of Huexotzinco, and the Mexica gained the support of a dissident Tepanec city called Tlacopan.

It has been alleged that Tlacaelel ordered the burning of some or most of the extant Aztec books, claiming that they contained lies and that it was "not wise that all the people should know the paintings".

[31] A second, more prestigious type of school called a "calmecac" served to teach the nobility, as well as commoners of high standing seeking to become priests or artisans.

Mesoamerican warfare overall is characterized by a strong preference for capturing live prisoners as opposed to slaughtering the enemy on the battlefield, which was considered sloppy and gratuitous.

[20][32] Native historical accounts say that these wars were instigated by Tlacaelel as a means of appeasing the gods in response to a massive drought that gripped the Basin of Mexico from 1450 to 1454.

[41] Building on the prestige the Mexica had acquired over the course of the conquests, Ahuitzotl began to use the title "huehuetlatoani" ("Eldest Speaker") to distinguish himself from the rulers of Texcoco and Tlacopan.

[44] At the island of Cozumel, Cortés encountered a shipwrecked Spaniard named Gerónimo de Aguilar who joined the expedition and translated between Spanish and Mayan.

The King of Campeche gave Cortés a second translator, a bilingual Nahua-Maya slave woman named La Malinche (she was known also as Malinalli [maliˈnalːi], Malintzin [maˈlintsin] or Doña Marina [ˈdoɲa maˈɾina]).

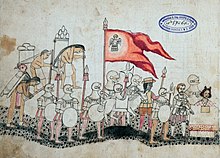

Cortés then secured an alliance with the people of Tlaxcala and traveled from there to the Basin of Mexico with a smaller company of 5,000-6,000 Tlaxcalans and 400 Totonacs in addition to the Spanish soldiers.

[48] In a pre-emptive response, Cortés directed his troops to attack and kill a large amount of unarmed Cholulans gathered in the main square of the city.

[48] Cortés was away from Tenochtitlan dealing with Narváez, while his second-in-command Pedro de Alvarado massacred a group of Aztec nobility, in response to a ritual of human sacrifice honoring Huitzilopochtli.

[49] The Spaniards and their allies attempted to retreat without detection in what is known as the "Sad Night" or La Noche Triste, realizing that they were vulnerable to the hostile Mexica in Tenochtitlan following Moctezuma's death.

[51] The new emperor Cuauhtémoc dealt with the smallpox outbreak, while Cortés raised an army of Tlaxcalans, Texcocans, Totonacs, and others discontent with Aztec rule.

Cortés captured various indigenous city-states or altepetl around the lake shore and surrounding mountains through numerous subsequent battles and skirmishes, including the other capitals of the Triple Alliance, Tlacopan and Texcoco.

Texcoco, in fact, had already become firm allies of the Spaniards and the city-state and subsequently petitioned the Spanish crown for recognition of their services in the conquest similar to Tlaxcala.

[52] Cortés used boats constructed in Texcoco from parts salvaged from the scuttled ships to blockade and lay siege to Tenochtitlan for a period of several months.

[58][59] Early in the history of the empire, Tenochtitlan developed a four-member military and advisory Council which assisted the Huey tlatoani in his decision-making: the tlacochcalcatl; the tlaccatecatl; the ezhuahuacatl;[60] and the tlillancalqui.

As has already been mentioned, directly appointed stewards (singular calpixqui, plural calpixque) were sometimes imposed on altepetl instead of the selection of provincial nobility to the same position of tlatoani.

These calpixque and huecalpixque were essentially managers of the provincial tribute system which was overseen and coordinated in the paramount capital of Tenochtitlan not by the huetlatoani, but rather by a separate position altogether: the petlacalcatl.

These pochteca had various gradations of ranks which granted them certain trading rights and so were not necessarily pipiltin themselves, yet they played an important role in both the growth and administration of the Aztec tributary system nonetheless.

[66][67] Nahua metaphysics centers around teotl, "a single, dynamic, vivifying, eternally self-generating and self-regenerating sacred power, energy or force.

[71] Priests and educated upper classes held more monistic views, while the popular religion of the uneducated tended to embrace the polytheistic and mythological aspects.

It was under Tlacaelel that Huitzilopochtli assumed his elevated role in the state pantheon and who argued that it was through blood sacrifice that the Sun would be maintained and thereby stave off the end of the world.