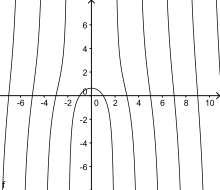

Quadratrix of Hippias

The discovery of this curve is attributed to the Greek sophist Hippias of Elis, who used it around 420 BC in an attempt to solve the angle trisection problem, hence its name as a trisectrix.

Later around 350 BC Dinostratus used it in an attempt to solve the problem of squaring the circle, hence its name as a quadratrix.

Dinostratus's theorem, used in this attempt, relates an endpoint of the curve to the value of π.

As Pappus of Alexandria observed, the curve formed by intersecting this helicoid with a non-vertical plane, when projected onto the

at the origin, then the quadratrix is described by a parametric equation that gives the coordinates of each point on the curve as a function of a time parameter

This description can also be used to give an analytical rather than a geometric definition of the quadratrix and to extend it beyond the

Removing the singularity in this way and extending the parametric definition to negative values of

yields a continuous planar curve on the range of parameter values

[5] When reflected left to right and scaled appropriately, the quadratrix forms the graph of the principal branch of the Lambert W function.

To describe the quadratrix as the graph of an unbranched function, it is advantageous to swap the

However, if the quadratrix is allowed as an additional tool, it is possible to divide an arbitrary angle into

equal parts with ruler and compass is possible due to the intercept theorem.

However, if one allows the quadratrix of Hippias as an additional construction tool, the squaring of the circle becomes possible due to Dinostratus's theorem relating an endpoint of this circle to the value of π.

According to Dinostratus's theorem the quadratrix divides one of the sides of the associated square in a ratio of

This is due to the fact that (as Sporus of Nicaea already observed) the two uniformly moving lines coincide and hence there exists no unique intersection point.

[11] However relying on the generalized definition of the quadratrix as a function or planar curve allows for

This rectangle can be transformed into a square of the same area with the help of Euclid's geometric mean theorem.

Inverting the quadratrix by a circle centered at the axis of the rotating line that defines it produces a cochleoid, and in the same way inverting the cochleoid produces a quadratrix.

[14] The quadratrix of Hippias is one of several curves used in Greek mathematics for squaring the circle, the most well-known for this purpose.

[15] It is mentioned in the works of Proclus (412–485), Pappus of Alexandria (3rd and 4th centuries) and Iamblichus (c. 240 – c. 325).

Pappus only mentions how a curve named a quadratrix was used by Dinostratus, Nicomedes and others to square the circle.

He relays the objections of Sporus of Nicaea to this construction, but neither mentions Hippias nor attributes the invention of the quadratrix to a particular person.

Iamblichus just writes in a single line, that a curve called a quadratrix was used by Nicomedes to square the circle.

[16][17][18] From Proclus' name for the curve, it is conceivable that Hippias himself used it for squaring the circle or some other curvilinear figure.

However, most historians of mathematics assume that Hippias invented the curve, but used it only for the trisection of angles.

According to this theory, its use for squaring the circle only occurred decades later and was due to mathematicians like Dinostratus and Nicomedes.

This interpretation of the historical sources goes back to the German mathematician and historian Moritz Cantor.

[5] However, other sources instead view Viète's formula as an elaboration of a method of nested polygons used by Archimedes to approximate

[19] In his 1637 book La Géométrie, René Descartes classified curves either as "geometric", admitting a precise geometric construction, or if not as "mechanical"; he gave the quadratrix as an example of a mechanical curve.

[20] Isaac Newton used trigonometric series to determine the area enclosed by the quadratrix.