Qualia

As qualitative characteristics of sensation, qualia stand in contrast to propositional attitudes,[1] where the focus is on beliefs about experience rather than what it is directly like to be experiencing.

Frank Jackson later defined qualia as "...certain features of the bodily sensations especially, but also of certain perceptual experiences, which no amount of purely physical information includes".

[2] Within the framework of mind, or nondualism, qualia may be considered comparable and analogous to the concepts of jñāna found in Eastern philosophy and traditions.

[5]: 121 Frank Jackson later defined qualia as "... certain features of the bodily sensations especially, but also of certain perceptual experiences, which no amount of purely physical information includes".

[10] Arguably, the idea of hedonistic utilitarianism, where the ethical value of things is determined from the amount of subjective pleasure or pain they cause, is dependent on the existence of qualia.

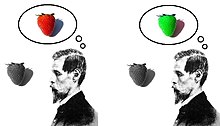

[15][16] In more detail:[citation needed] The argument thus claims that if we find the inverted spectrum plausible, we must admit that qualia exist (and are non-physical).

find it absurd that armchair theorizing can prove something to exist, and the detailed argument does involve a lot of assumptions about conceivability and possibility, which are open to criticism.

[16][19] As Alex Byrne puts it: ...there are more perceptually distinguishable shades between red and blue than there are between green and yellow, which would make red-green inversion behaviorally detectable.

George M. Stratton, professor of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley, performed an experiment in which he wore special prism glasses that caused the external world to appear upside down.

He claims that "if we acknowledge that a physical theory of mind must account for the subjective character of experience, we must admit that no presently available conception gives us a clue about how this could be done.

[27] The argument holds that it is conceivable for a person to have a duplicate, identical in every physical way, but lacking consciousness, called a "philosophical zombie."

[17]However, such an epistemological or explanatory problem might indicate an underlying metaphysical issue, as even if not proven by conceivability arguments, the non-physicality of qualia is far from ruled out.

She specializes in the neurophysiology of vision and acquires all the physical information there is to obtain about what goes on when we see ripe tomatoes or the sky and use terms like "red", "blue", and so on.

He concluded that there must be an issue with the knowledge argument, eventually embracing a representationalist account, arguing that sensory experiences can be understood in physical terms.

[31] David Chalmers formulated the hard problem of consciousness, which raised the issue of qualia to a new level of importance and acceptance in the field of the philosophy of mind.

[33] E. J. Lowe denies that indirect realism, wherein which we have access only to sensory features internal to the brain, necessarily implies a Cartesian dualism.

[34] John Barry Maund, an Australian philosopher of perception, argues that qualia can be described on two levels, a fact that he refers to as "dual coding".

In his book Sensing the World,[37] Moreland Perkins argues that qualia need not be identified as their objective sources: a smell, for instance, bears no direct resemblance to the molecular shape that gives rise to it, nor is a toothache actually in the tooth.

[42] In his book Bright Air, Brilliant Fire, neuroscientist and Nobel laureate in Physiology / Medicine Gerald Edelman says "that [it] definitely does not seem feasible [...] to ignore completely the reality of qualia".

[44]: 308 Neurologist Rodolfo Llinás states in his book I of the Vortex that qualia, from a neurological perspective, are essential for an organism's survival and played a key role in the evolution of nervous systems, including in simple creatures like ants or cockroaches.

[46] For example, the discovery of relativity in physics was not the product of accepting Occam's razor but rather of rejecting it and asking the question of whether a deeper generalization, not required by the currently available data, was true and would allow for unexpected predictions.

[51]: 28 Dennett uses this example as an attempt to show us that Mary's all-encompassing physical knowledge makes her own internal states as transparent as those of a robot or computer, and it is as straightforward for her to figure out exactly how it feels to see red.

An alien race with a different method of communication or description might be perfectly able to teach their version of Mary exactly how seeing the color red would feel.

Similarly, Dennett proposes, it is perfectly, logically, possible that the quale of what it is like to see red could eventually be described in an English-language description of millions or billions of words.

[49] In Are we explaining consciousness yet?,[52] Dennett approves of an account of qualia defined as the deep, rich collection of individual neural responses that are too fine-grained for language to capture.

Drescher explains, "we have no introspective access to whatever internal properties make the red gensym recognizably distinct from the green [...] even though we know the sensation when we experience it.

"[54] Under this interpretation of qualia, Drescher responds to the Mary thought experiment by noting that "knowing about red-related cognitive structures and the dispositions they engender – even if that knowledge were implausibly detailed and exhaustive – would not necessarily give someone who lacks prior color-experience the slightest clue whether the card now being shown is of the color called red."

[24]: 58–59 Tye proposes that phenomenal experience has five basic elements, for which he has coined the acronym PANIC – Poised, Abstract, Nonconceptual, Intentional Content.

[57] Roger Scruton, while skeptical that neurobiology can tell us much about consciousness, believes qualia is an incoherent concept, and that Wittgenstein's private language argument effectively disproves it.

Leibniz's passage in Monadology describing the explanatory gap goes as follows:It must be confessed, moreover, that perception, and that which depends on it, are inexplicable by mechanical causes, that is, by figures and motions.