Quantum annealing

The term "quantum annealing" was first proposed in 1988 by B. Apolloni, N. Cesa Bianchi and D. De Falco as a quantum-inspired classical algorithm.

[2][3] It was formulated in its present form by T. Kadowaki and H. Nishimori (ja) in 1998,[4] though an imaginary-time variant without quantum coherence had been discussed by A.

If the rate of change of the transverse field is slow enough, the system stays close to the ground state of the instantaneous Hamiltonian (also see adiabatic quantum computation).

[6] If the rate of change of the transverse field is accelerated, the system may leave the ground state temporarily but produce a higher likelihood of concluding in the ground state of the final problem Hamiltonian, i.e., Diabatic quantum computation.

[7][8] The transverse field is finally switched off, and the system is expected to have reached the ground state of the classical Ising model that corresponds to the solution to the original optimization problem.

An experimental demonstration of the success of quantum annealing for random magnets was reported immediately after the initial theoretical proposal.

[9] Quantum annealing has also been proven to provide a fast Grover oracle for the square-root speedup in solving many NP-complete problems.

In quantum annealing, the strength of transverse field determines the quantum-mechanical probability to change the amplitudes of all states in parallel.

The whole process can be simulated in a computer using quantum Monte Carlo (or other stochastic technique), and thus obtain a heuristic algorithm for finding the ground state of the classical glass.

Then one may carry out the simulation with the quantum Hamiltonian thus constructed (the original function + non-commuting part) just as described above.

), quantum fluctuations can surely bring the system out of the shallow local minima.

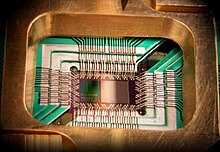

[19][20] Timeline of ideas related to quantum annealing in Ising spin glasses: In 2011, D-Wave Systems announced the first commercial quantum annealer on the market by the name D-Wave One and published a paper in Nature on its performance.

[24] On October 28, 2011 University of Southern California's (USC) Information Sciences Institute took delivery of Lockheed's D-Wave One.

In May 2013, it was announced that a consortium of Google, NASA Ames and the non-profit Universities Space Research Association purchased an adiabatic quantum computer from D-Wave Systems with 512 qubits.

[27] In June 2014, D-Wave announced a new quantum applications ecosystem with computational finance firm 1QB Information Technologies (1QBit) and cancer research group DNA-SEQ to focus on solving real-world problems with quantum hardware.

[28] As the first company dedicated to producing software applications for commercially available quantum computers, 1QBit's research and development arm has focused on D-Wave's quantum annealing processors and has demonstrated that these processors are suitable for solving real-world applications.

Several definitions were put forward as some may be unverifiable by empirical tests, while others, though falsified, would nonetheless allow for the existence of performance advantages.

The study found that the D-Wave chip "produced no quantum speedup" and did not rule out the possibility in future tests.

Further work[33] has advanced understanding of these test metrics and their reliance on equilibrated systems, thereby missing any signatures of advantage due to quantum dynamics.

Researchers at Google, LANL, USC, Texas A&M, and D-Wave are working to find such problem classes.

[34] In December 2015, Google announced that the D-Wave 2X outperforms both simulated annealing and Quantum Monte Carlo by up to a factor of 100,000,000 on a set of hard optimization problems.

[citation needed] Shor's algorithm requires a universal quantum computer.

"A cross-disciplinary introduction to quantum annealing-based algorithms" [37] presents an introduction to combinatorial optimization (NP-hard) problems, the general structure of quantum annealing-based algorithms and two examples of this kind of algorithms for solving instances of the max-SAT (maximum satisfiable problem) and Minimum Multicut problems, together with an overview of the quantum annealing systems manufactured by D-Wave Systems.

Hybrid quantum-classic algorithms for large-scale discrete-continuous optimization problems were reported to illustrate the quantum advantage.