Coherent state

[2] For instance, a coherent state describes the oscillating motion of a particle confined in a quadratic potential well (for an early reference, see e.g. Schiff's textbook[3]).

This state can be related to classical solutions by a particle oscillating with an amplitude equivalent to the displacement.

[1] It is a minimum uncertainty state, with the single free parameter chosen to make the relative dispersion (standard deviation in natural dimensionless units) equal for position and momentum, each being equally small at high energy.

Further, in contrast to the energy eigenstates of the system, the time evolution of a coherent state is concentrated along the classical trajectories.

While minimum uncertainty Gaussian wave-packets had been well-known, they did not attract full attention until Roy J. Glauber, in 1963, provided a complete quantum-theoretic description of coherence in the electromagnetic field.

Sudarshan should not be omitted,[9] (there is, however, a note in Glauber's paper that reads: "Uses of these states as generating functions for the

Glauber was prompted to do this to provide a description of the Hanbury-Brown & Twiss experiment, which generated very wide baseline (hundreds or thousands of miles) interference patterns that could be used to determine stellar diameters.

That is a positive feedback loop in which the amplitude in the resonant mode increases exponentially until some nonlinear effects limit it.

See Fig.1) Besides describing lasers, coherent states also behave in a convenient manner when describing the quantum action of beam splitters: two coherent-state input beams will simply convert to two coherent-state beams at the output with new amplitudes given by classical electromagnetic wave formulas;[11] such a simple behaviour does not occur for other input states, including number states.

Likewise if a coherent-state light beam is partially absorbed, then the remainder is a pure coherent state with a smaller amplitude, whereas partial absorption of non-coherent-state light produces a more complicated statistical mixed state.

A coherent state distributes its quantum-mechanical uncertainty equally between the canonically conjugate coordinates, position and momentum, and the relative uncertainty in phase [defined heuristically] and amplitude are roughly equal—and small at high amplitude.

is defined to be the (unique) eigenstate of the annihilation operator â with corresponding eigenvalue α.

Physically, this formula means that a coherent state remains unchanged by the annihilation of field excitation or, say, a charged particle.

[12] With these (dimensionless) operators, the Hamiltonian of either system becomes Erwin Schrödinger was searching for the most classical-like states when he first introduced minimum uncertainty Gaussian wave-packets.

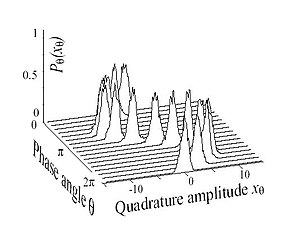

The coherent state's location in the complex plane (phase space) is centered at the position and momentum of a classical oscillator of the phase θ and amplitude |α| given by the eigenvalue α (or the same complex electric field value for an electromagnetic wave).

As shown in Figure 5, the uncertainty, equally spread in all directions, is represented by a disk with diameter 1⁄2.

As the phase varies, the coherent state circles around the origin and the disk neither distorts nor spreads.

The formal solution of the eigenvalue equation is the vacuum state displaced to a location α in phase space, i.e., it is obtained by letting the unitary displacement operator D(α) operate on the vacuum, where â = X + iP and ↠= X - iP.

are energy (number) eigenvectors of the Hamiltonian and the final equality derives from the Baker-Campbell-Hausdorff formula.

So in the limit of large α, these detection statistics are equivalent to that of a classical stable wave.

Hanbury Brown and Twiss studied the correlation behavior of photons emitted from a thermal, incoherent source described by Bose–Einstein statistics.

Roy J. Glauber's work was prompted by the results of Hanbury-Brown and Twiss that produced long-range (hundreds or thousands of miles) first-order interference patterns through the use of intensity fluctuations (lack of second order coherence), with narrow band filters (partial first order coherence) at each detector.

He coined the term coherent state and showed that they are produced when a classical electric current interacts with the electromagnetic field.

It is easy to see that, in the Schrödinger picture, the same eigenvalue occurs, In the coordinate representations resulting from operating by

The mean position and momentum of this "minimal Schrödinger wave packet" ψ(α) are thus oscillating just like a classical system,

[23] The above resolution of the identity may be derived (restricting to one spatial dimension for simplicity) by taking matrix elements between eigenstates of position,

On the left-hand side, the same is obtained by inserting from the previous section (time is arbitrary), then integrating over

In particular, the Gaussian Schrödinger wave-packet state follows from the explicit value The resolution of the identity may also be expressed in terms of particle position and momentum.

The average number of photons in that state can be calculated as below where for the last term we can write As a result, we find where

The distribution of the initial thermal state in phase space broadens as a result of the coherent displacement.