Quaternion

Quaternions were first described by the Irish mathematician William Rowan Hamilton in 1843[1][2] and applied to mechanics in three-dimensional space.

[5] Quaternions are used in pure mathematics, but also have practical uses in applied mathematics, particularly for calculations involving three-dimensional rotations, such as in three-dimensional computer graphics, computer vision, robotics, magnetic resonance imaging[6] and crystallographic texture analysis.

Further extending the quaternions yields the non-associative octonions, which is the last normed division algebra over the real numbers.

The great breakthrough in quaternions finally came on Monday 16 October 1843 in Dublin, when Hamilton was on his way to the Royal Irish Academy to preside at a council meeting.

As he walked along the towpath of the Royal Canal with his wife, the concepts behind quaternions were taking shape in his mind.

On the following day, Hamilton wrote a letter to his friend and fellow mathematician, John T. Graves, describing the train of thought that led to his discovery.

This letter was later published in a letter to the London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science;[14] Hamilton states: And here there dawned on me the notion that we must admit, in some sense, a fourth dimension of space for the purpose of calculating with triples ... An electric circuit seemed to close, and a spark flashed forth.

[14]Hamilton called a quadruple with these rules of multiplication a quaternion, and he devoted most of the remainder of his life to studying and teaching them.

The last and longest of his books, Elements of Quaternions,[15] was 800 pages long; it was edited by his son and published shortly after his death.

After Hamilton's death, the Scottish mathematical physicist Peter Tait became the chief exponent of quaternions.

From the mid-1880s, quaternions began to be displaced by vector analysis, which had been developed by Josiah Willard Gibbs, Oliver Heaviside, and Hermann von Helmholtz.

However, vector analysis was conceptually simpler and notationally cleaner, and eventually quaternions were relegated to a minor role in mathematics and physics.

However, quaternions have had a revival since the late 20th century, primarily due to their utility in describing spatial rotations.

[19] The finding of 1924 that in quantum mechanics the spin of an electron and other matter particles (known as spinors) can be described using quaternions (in the form of the famous Pauli spin matrices) furthered their interest; quaternions helped to understand how rotations of electrons by 360° can be discerned from those by 720° (the "Plate trick").

[c] Multiplication of quaternions is associative and distributes over vector addition, but with the exception of the scalar subset, it is not commutative.

Hamilton[28] showed that this product computes the third vertex of a spherical triangle from two given vertices and their associated arc-lengths, which is also an algebra of points in Elliptic geometry.

There exist 48 distinct matrix representations of this form in which one of the matrices represents the scalar part and the other three are all skew-symmetric.

[citation needed][d] Each antipodal pair of square roots of −1 creates a distinct copy of the complex numbers inside the quaternions.

is the union of the images of all these homomorphisms, one can view the quaternions as a pencil of planes intersecting on the real line.

as a union of complex planes arises when one seeks to find all commutative subrings of the quaternion ring.

For example, the original electric and magnetic fields described by Maxwell were functions of a quaternion variable.

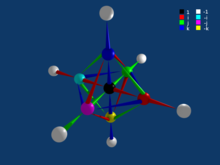

The double cover of the rotational symmetry group of the regular octahedron corresponds to the quaternions that represent the vertices of the disphenoidal 288-cell.

Take F to be any field with characteristic different from 2, and a and b to be elements of F; a four-dimensional unitary associative algebra can be defined over F with basis 1, i, j, and i j, where i2 = a, j2 = b and i j = −j i (so (i j)2 = −a b).

This is an associative multivector algebra built up from fundamental basis elements σ1, σ2, σ3 using the product rules

The relation to complex numbers becomes clearer, too: in 2D, with two vector directions σ1 and σ2, there is only one bivector basis element σ1σ2, so only one imaginary.

... And how the One of Time, of Space the Three, Might in the Chain of Symbols girdled be.Quaternions came from Hamilton after his really good work had been done; and, though beautifully ingenious, have been an unmixed evil to those who have touched them in any way, including Clerk Maxwell.There was a time, indeed, when I, although recognizing the appropriateness of vector analysis in electromagnetic theory (and in mathematical physics generally), did think it was harder to understand and to work than the Cartesian analysis.

This was, however, a complete mistake: The ancients – unlike Prof. Tait – knew not, and did not worship Quaternions.Neither matrices nor quaternions and ordinary vectors were banished from these ten [additional] chapters.

For, in spite of the uncontested power of the modern Tensor Calculus, those older mathematical languages continue, in my opinion, to offer conspicuous advantages in the restricted field of special relativity.

Moreover, in science as well as in everyday life, the mastery of more than one language is also precious, as it broadens our views, is conducive to criticism with regard to, and guards against hypostasy [weak-foundation] of, the matter expressed by words or mathematical symbols.... quaternions appear to exude an air of nineteenth century decay, as a rather unsuccessful species in the struggle-for-life of mathematical ideas.

Mathematicians, admittedly, still keep a warm place in their hearts for the remarkable algebraic properties of quaternions but, alas, such enthusiasm means little to the harder-headed physical scientist.

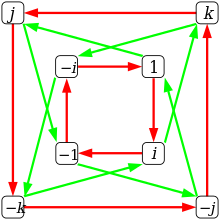

-

In

blue

:

- 1 ⋅ i = i (1/ i plane)

- i ⋅ j = k ( i / k plane)

-

In

red

:

- 1 ⋅ j = j (1/ j plane)

- j ⋅ i = − k ( j / k plane)

Here as he walked by

on the 16th of October 1843

Sir William Rowan Hamilton

in a flash of genius discovered

the fundamental formula for

quaternion multiplication

i

2

=

j

2

=

k

2

=

i

j

k

= −1

& cut it on a stone of this bridge