Mary I of England

When Edward became terminally ill in 1553, he attempted to remove Mary from the line of succession because he supposed, correctly, that she would reverse the Protestant reforms that had taken place during his reign.

[5] Henry VIII's first cousin once removed, Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury, stood sponsor for Mary's confirmation, which was conducted immediately after the baptism.

[21] She appears to have spent three years in the Welsh Marches, making regular visits to her father's court, before returning permanently to the home counties around London in mid-1528.

In 1528, Wolsey's agent Thomas Magnus discussed the idea of Mary marrying her cousin James V of Scotland with the Scottish diplomat Adam Otterburn.

Disappointed at the lack of a male heir, and eager to remarry, Henry attempted to have his marriage to Catherine annulled, but Pope Clement VII refused his request.

Henry claimed, citing biblical passages (Leviticus 20:21), that the marriage was unclean because Catherine was the widow of his brother Arthur, Prince of Wales (Mary's uncle).

Clement VII may have been reluctant to act because he was influenced by Charles V, Catherine's nephew and Mary's former betrothed, whose troops had sacked Rome in the War of the League of Cognac.

[44] Henry insisted that Mary recognise him as head of the Church of England, repudiate papal authority, acknowledge that the marriage between her parents was unlawful, and accept her own illegitimacy.

[54] When the King saw Anne for the first time in late December 1539, a week before the scheduled wedding, he found her unattractive but was unable, for diplomatic reasons and without a suitable pretext, to cancel the marriage.

[72] Therefore, instead of heading to London from her residence at Hunsdon, Mary fled to East Anglia, where she owned extensive estates and Northumberland had ruthlessly put down Kett's Rebellion.

[74] On 10 July 1553, Lady Jane was proclaimed queen by Northumberland and his supporters, and on the same day Mary's servant, Thomas Hungate, arrived in London with her letter to the council.

[79] One of Mary's first actions as queen was to order the release of the Roman Catholic Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, and Stephen Gardiner from imprisonment in the Tower of London, as well as her kinsman Edward Courtenay.

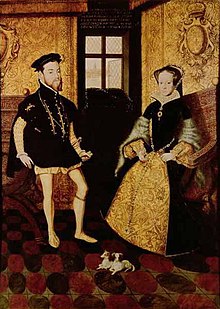

[84] Now aged 37, Mary turned her attention to finding a husband and producing an heir, which would prevent the Protestant Elizabeth (still next in line under the terms of Henry VIII's will and the Act of Succession of 1544) from succeeding to the throne.

[85] On 16 November 1553, a parliamentary delegation went to her and formally requested that she choose an English husband,[86] with its obvious although tacit candidates being her kinsmen Edward Courtenay, recently created Earl of Devon, and the Catholic Cardinal Reginald Pole.

[87] The Spanish prince had been widowed a few years before by the death of his first wife, Maria Manuela of Portugal, mother of his son Carlos and was the heir apparent to vast territories in Continental Europe and the New World.

[90] This was of particular concern to the landed gentry and parliamentary classes, who foresaw having to pay greater taxes to cover the cost of England's participation in foreign wars.

[91] Lord Chancellor Gardiner and the English House of Commons unsuccessfully petitioned Mary to consider marrying an Englishman, fearing that England would be relegated to a dependency of the Habsburgs.

Further, under the English common law doctrine of jure uxoris, the property and titles belonging to a woman became her husband's upon marriage, and it was feared that any man she married would thereby become king of England in fact and name.

[118] In August, soon after the disgrace of the false pregnancy, which Mary considered "God's punishment" for her having "tolerated heretics" in her realm,[119][full citation needed] Philip left England to command his armies against France in Flanders.

[122] In the absence of any children, Philip was concerned that one of the next claimants to the English throne after his sister-in-law was Mary, Queen of Scots, who was betrothed to Francis, Dauphin of France.

Reaching an agreement took many months and Mary and Pope Julius III had to make a major concession: the confiscated monastery lands were not returned to the church but remained in the hands of their influential new owners.

[134] The burnings proved so unpopular that even Alfonso de Castro, one of Philip's own ecclesiastical staff, condemned them[135] and another adviser, Simon Renard, warned him that such "cruel enforcement" could "cause a revolt".

Mary, concerned about her sister's religious convictions (Elizabeth only attended mass under obligation and had only superficially converted to Catholicism to save her life after being imprisoned following Wyatt's rebellion, although she remained a staunch Protestant), seriously considering the possibility of removing her from the succession and naming as her successor her Scottish first cousin and devout Catholic, Margaret Douglas.

The next month, the French ambassador in England, Antoine de Noailles, was implicated in a plot against Mary when Henry Dudley, a second cousin of the executed Duke of Northumberland, attempted to assemble an invasion force in France.

[146] War was only declared in June 1557 after Reginald Pole's nephew Thomas Stafford invaded England and seized Scarborough Castle with French help, in a failed attempt to depose Mary.

[159] Mary retained the Edwardian appointee William Paulet, 1st Marquess of Winchester, as Lord High Treasurer and assigned him to oversee the revenue collection system.

[165] In pain, possibly from ovarian cysts or uterine cancer,[166] she died on 17 November 1558, aged 42, at St James's Palace, during an influenza epidemic that also claimed Archbishop Pole's life later that day.

"[130] Mary is remembered in the 21st century for her vigorous efforts to restore the primacy of Roman Catholicism in England after the rise of Protestant influence during the previous reigns.

[177] Catholic historians, such as John Lingard, thought Mary's policies failed not because they were wrong but because she had too short a reign to establish them and because of natural disasters beyond her control.

[185] Mary I's coat of arms was the same as those used by all her predecessors since Henry IV: Quarterly, Azure three fleurs-de-lys Or [for France] and Gules three lions passant guardant in pale Or (for England).