Queen of Sheba

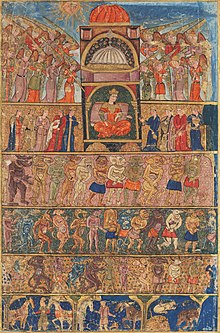

This account has undergone extensive Jewish, Islamic, Yemenite and Ethiopian elaborations,[1][2] and it has become the subject of one of the most widespread and fertile cycles of legends in Asia and Africa.

[3] Modern historians and archaeologists identify Sheba as the ancient South Arabian kingdom of Saba that existed in modern-day Yemen, although no trace of the queen herself has been found.

[11][12] The use of the term ḥiddot or 'riddles' (1 Kings 10:1), an Aramaic loanword whose shape points to a sound shift no earlier than the sixth century BC, indicates a late origin for the text.

[11] A recent theory suggests that the Ophel inscription in Jerusalem was written in the Sabaic language and that the text provides evidence for trade connections between ancient South Arabia and the Kingdom of Judah during the 10th century BC.

[20] The ancient Sabaic Awwām Temple, known in folklore as Maḥram ("the Sanctuary of") Bilqīs, was recently excavated by archaeologists, but no trace of the Queen of Sheba has been discovered so far in the many inscriptions found there.

[22] Christian scriptures mention a "queen of the South" (Greek: βασίλισσα νότου, Latin: Regina austri), who "came from the uttermost parts of the earth", i.e. from the extremities of the then known world, to hear the wisdom of Solomon (Mt.

[24] The bride of the Canticles is assumed to have been black due to a passage in Song of Songs 1:5, which the Revised Standard Version (1952) translates as "I am very dark, but comely", as does Jerome (Latin: Nigra sum, sed formosa), while the New Revised Standard Version (1989) has "I am black and beautiful", as the Septuagint (Ancient Greek: μέλαινα εἰμί καί καλή).

[29] The most extensive version of the legend appears in the Kebra Nagast (Glory of the Kings), the Ethiopian national saga,[30] translated from Arabic in 1322.

While the Abyssinian story offers much greater detail, it omits any mention of the Queen's hairy legs or any other element that might reflect on her unfavourably.

Prior to leaving, the priests' sons had stolen the Ark of the Covenant, after their leader Azaryas had offered a sacrifice as commanded by one God's angel.

Solomon returned to Jerusalem and gave orders to the priests to remain silent about the theft and to place a copy of the Ark in the Temple, so that the foreign nations could not say that Israel had lost its fame.

The family's intended choice to rule Aksum was Makeda's brother, Prince Nourad, but his early death led to her succession to the throne.

[42] The tradition that the biblical Queen of Sheba was an ingenuous ruler of Ethiopia who visited King Solomon in Jerusalem is repeated in a 1st-century account by Josephus.

[36] According to one tradition, the Ethiopian Jews (Beta Israel, "Falashas") also trace their ancestry to Menelik I, son of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba.

[44] An opinion that appears more historical is that the Falashas descend from those Jews who settled in Egypt after the first exile, and who, upon the fall of the Persian domination (539–333 BC), on the borders of the Nile, penetrated into the Sudan, whence they went into the western parts of Abyssinia.

[49][obsolete source] The Talmud (Bava Batra 15b) insists that it was not a woman but a kingdom of Sheba (based on varying interpretations of Hebrew mlkt) that came to Jerusalem.

When the queen arrived and came to Solomon's palace, thinking that the glass floor was a pool of water, she lifted the hem of her dress, uncovering her legs.

In an act suggesting the diplomatic qualities of her leadership,[55] she responds not with brute force, but by sending her ambassadors to present a gift to King Solomon.

Before she arrives, King Solomon asks several of his chiefs who will bring him the Queen of Sheba's throne before they come to him in complete submission.

Here they claim that the Queen's name is Bilqīs (Arabic: بِلْقِيْس), probably derived from Greek: παλλακίς, romanized: pallakis or the Hebraised pilegesh ("concubine").

[64] According to E. Ullendorff, the Quran and its commentators have preserved the earliest literary reflection of her complete legend, which among scholars complements the narrative that is derived from a Jewish tradition,[3] this assuming to be the Targum Sheni.

believe that the account from the Third Book of Kings in its present form was compiled during the so-called Second Deuteronomic Revision (Dtr2), produced during the Babylonian Captivity (c. 550 BCE).

[71] There is, however, debate about the chronological plausibility of this event: Solomon lived from approximately 965 to 926 BC, while it has been argued that the first traces of the Sabean monarchy appear some 150 years later.

As it turned out, the residence of the kings of Sheba was the city of Marib (modern Yemen), which confirms the traditional version of the queen's origin from the south of the Arabian Peninsula.

[80] For example, it is told (by one of Mohammed's biographers) that it was in Palmyra, in the 8th century during the reign of Caliph Walid I, that a sarcophagus was found with the inscription: 'Here is buried the pious Bilqis, the consort of Solomon...'.

[81] There are also parallels between Sheba and another eastern autocrat, the famous Semiramis, also a warrior and irrigator who lived around the same time, in the late 9th century BC, which can be traced in folklore.

[11] The 12th century cathedrals at Strasbourg, Chartres, Rochester and Canterbury include artistic renditions in stained glass windows and doorjamb decorations.

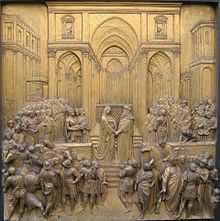

It appears in the bronze doors to the Florence Baptistery by Lorenzo Ghiberti, in frescoes by Benozzo Gozzoli (Campo Santo, Pisa) and in the Raphael Loggie (Vatican).

Therein, Kipling identifies Balkis, "Queen that was of Sheba and Sable and the Rivers of the Gold of the South" as best, and perhaps only, beloved of the 1000 wives of Suleiman-bin-Daoud, King Solomon.

She is portrayed as a vain woman who, fearing Solomon's great power, sends the captain of her royal guard to assassinate him, setting the events of the book in motion.