Quetzalcoatlus

The type specimen, recovered in 1971 from the Javelina Formation of Texas, United States, consists of several wing fragments and was described as Quetzalcoatlus northropi in 1975 by Douglas Lawson.

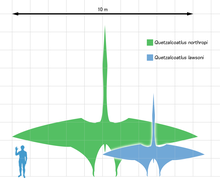

Quetzalcoatlus northropi has gained fame as a candidate for the largest flying animal ever discovered, though estimating its size has been difficult due to the fragmentary nature of the only known specimen.

Based on the work of Mark P. Witton and Michael Habib in 2010, it now seems likely that pterosaurs, especially larger taxa such as Quetzalcoatlus, launched quadrupedally (from a four-legged posture), using the powerful muscles of their forelimbs to propel themselves off the ground and into the air.

The genus Quetzalcoatlus is based on fossils discovered in rocks pertaining to the Late Cretaceous Javelina Formation in Big Bend National Park, Texas.

The first Quetzalcoatlus fossils were discovered in 1971 by the graduate student Douglas A. Lawson while conducting field work for his Master's degree project on the paleoecology of the Javelina Formation.

[2] Lawson announced his discovery in the journal Science in March of 1975, with a depiction of the animal's size compared to a large aircraft and a Pteranodon gracing the cover of the issue.

[3] Prior to the announcement of the discovery, Langston had returned to Big Bend with a group of fossil preparators in February 1973, primarily aiming to excavate bones of the dinosaur Alamosaurus.

[2][3] Two more new sites quickly followed nearby, producing many fragments which the crew figured could be fit back together, in addition to a complete carpal and intact wing bone.

The model was created to understand the flight of the animal — prior to Lawson's discovery such a large flier wasn't thought possible, and the subject remained controversial at the time.

Despite not contributing directly to the written manuscript, the authors of the memoir and Langston's family agreed that he posthumously be considered a co-author of this paper due the basis of the work in the decades of research he dedicates to the subject.

[16] Finally, a study on the functional morphology of the genus was authored by Padian, James Cunningham, and John Conway (who contributed scientific illustrations and cover art to the Memoir[3]), with Langston once again considered a posthumous co-author due to his foundational work on the subject.

Regarding the genus Quetzalcoatlus and species Q. northropi, the establishment of both names were not associated with any kind of description of what distinguished the animal from others (as the material was described in a separate publication).

[3] In 1982, fragmentary azhdarchid remains, in the form of a wing phalanx, a partial femur, a vertebra and a tibia, were uncovered in strata from the Dinosaur Park Formation of Canada.

[26] An azhdarchid cervical (neck) vertebra (BMR P2002.2), discovered in 2002 in strata from the Maastrichtian age Hell Creek Formation (alongside a Tyrannosaurus rex specimen), was originally assigned to Quetzalcoatlus.

The aspect ratio of azhdarchid wings is 8.1, similar to that of storks and birds of prey that engage in static soaring (relying on air currents to gain altitude and remain aloft).

[6] A majority of estimates published since the 2000s have hovered around 200–250 kg (440–550 lb),[36][33] due largely to a greater understanding of how aberrant the anatomy of azhdarchids was in comparison to other pterosaur clades.

[41] Quetzalcoatlus and other azhdarchids have forelimb and hind limb proportions more similar to modern running ungulate mammals than to members of other pterosaur clades, implying that they were uniquely suited to a terrestrial lifestyle.

[13] When describing Quetzalcoatlus in 1975, Douglas Lawson and Crawford Greenewalt opted not to assign it to a clade more specific than Pterodactyloidea,[6] though comparisons with Arambourgiania (then Titanopteryx) from Jordan had been drawn earlier that year.

[42] Unaware of that subfamily, in the same year, Kevin Padian erected the family Titanopterygiidae to accommodate Quetzalcoatlus and Titanopteryx, defining it based on the length and general morphology of the cervical vertebrae.

[45] In the supplementary material for their 2014 paper describing Kryptodrakon progenitor, Andres, James Clark and Xing Xu named a new subfamily, Quetzalcoatlinae, of which Quetzalcoatlus is the type genus.

Eurazhdarcho langendorfensis Phosphatodraco mauritanicus Aralazhdarcho bostobensis Zhejiangopterus linhaiensis Azhdarcho lancicollis Arambourgiania philadelphiae Aerotitan sudamericanus Mistralazhdarcho maggii Hatzegopteryx thambema Albadraco tharmisensis Cryodrakon boreas Thanatosdrakon amaru Quetzalcoatlus lawsoni aff.

Their long, stiffened necks would be an advantage as it would help lowering and raising the head and give it a vantage point when searching for prey, and enable them to grab small animals and fruit.

[50] Q. northropi is found in plains deposits, and due to the paucity and location of its remains, was speculated by Thomas Lehman to have been a solitary hunter that favoured riparian environments.

Studies of azhdarchid flight abilities indicate they would have been able to fly for long and probably fast (especially if they had an adequate amount of fat and muscle as nourishment), so that geographical barriers would not present obstacles.

One long trackway of this kind shows that azhdarchids walked with their limbs held directly underneath their body, and along with the morphology of their feet indicates they were more proficient on the ground than other pterosaurs.

In 2010, Mike Habib, a professor of biomechanics at Chatham University, and Mark Witton, a British paleontologist, undertook further investigation into the claims of flightlessness in large pterosaurs.

After factoring wingspan, body weight, and aerodynamics, computer modeling led the two researchers to conclude that Q. northropi was capable of flight up to 130 km/h (80 mph) for 7 to 10 days at altitudes of 4,600 m (15,000 ft).

[28][3] The depositional environment represents a floodplain which was probably semi-arid, analogous in terms of climate and flora to the coastal plains of southern Mexico, consisting of an evergreen or semideciduous tropical forest,[56][15] with a mean annual temperature of 16–22 °C (61–72 °F).

[15] These forests consisted largely of angiosperm trees such as Javelinoxylon, conifers related to the modern Araucaria, and woody vines, with a closed canopy in excess of 30 m (98 ft) in height.

[15] In 1975, artist Giovanni Caselli depicted Quetzalcoatlus as a small-headed scavenger with an extremely long neck in the book The evolution and ecology of the Dinosaurs[62] by British paleontologist Beverly Halstead.