Q.E.D.

or QED is an initialism of the Latin phrase quod erat demonstrandum, meaning "that which was to be demonstrated".

The phrase quod erat demonstrandum is a translation into Latin from the Greek ὅπερ ἔδει δεῖξαι (hoper edei deixai; abbreviated as ΟΕΔ).

However, translating the Greek phrase ὅπερ ἔδει δεῖξαι can produce a slightly different meaning.

In particular, since the verb "δείκνυμι" means both to show or to prove,[2] a different translation from the Greek phrase would read "The very thing it was required to have shown.

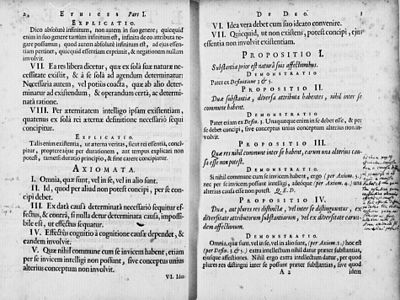

is used once in 1598 by Johannes Praetorius,[6] more in 1643 by Anton Deusing,[7] extensively in 1655 by Isaac Barrow in the form Q.E.D.,[8] and subsequently by many post-Renaissance mathematicians and philosophers.

The style and system of the book are, as Spinoza says, "demonstrated in geometrical order", with axioms and definitions followed by propositions.

For Spinoza, this is a considerable improvement over René Descartes's writing style in the Meditations, which follows the form of a diary.

Quod erat faciendum, originating from the Greek geometers' closing ὅπερ ἔδει ποιῆσαι (hoper edei poiēsai), meaning "which had to be done".

In printed English language texts, the formal statements of theorems, lemmas, and propositions are set in italics by tradition.

Paul Halmos claims to have pioneered the use of a solid black square (or rectangle) at the end of a proof as a Q.E.D.

Often the Halmos symbol is drawn on chalkboard to signal the end of a proof during a lecture, although this practice is not so common as its use in printed text.

Some authors use other Unicode symbols to note the end of a proof, including, ▮ (U+25AE, a black vertical rectangle), and ‣ (U+2023, a triangular bullet).