Race and genetics

Researchers have investigated the relationship between race and genetics as part of efforts to understand how biology may or may not contribute to human racial categorization.

[2][11] The mainstream view is that it is necessary to distinguish between biology and the social, political, cultural, and economic factors that contribute to conceptions of race.

[17] The concept of "race" as a classification system of humans based on visible physical characteristics emerged over the last five centuries, influenced by European colonialism.

In Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza's book (circa 1994) "The History and Geography of Human Genes"[36] he writes, "From a scientific point of view, the concept of race has failed to obtain any consensus; none is likely, given the gradual variation in existence.

However, this theory has since been discarded, with one of the main reasons being that purebred dogs have been specifically bred artificially, whereas human races developed organically.

(Measurements of the latter through craniometry were repeatedly discredited in the late 19th and mid-20th centuries due to a lack of correlation of phenotypic traits with racial categorization.

Edwards saw Lewontin's argument as based on a political stance, denying biological differences to argue for social equality.

[57] Edwards' paper is reprinted, commented upon by experts such as Noah Rosenberg, and given further context in an interview with philosopher of science Rasmus Grønfeldt Winther in a recent anthology.

[59] Sesardic also strengthened Edwards' view, as he used an illustration referring to squares and triangles, and showed that if you look at one trait in isolation, then it will most likely be a bad predicator of which group the individual belongs to.

[60] In contrast, in a 2014 paper, reprinted in the 2018 Edwards Cambridge University Press volume, Rasmus Grønfeldt Winther argues that "Lewontin's Fallacy" is effectively a misnomer, as there really are two different sets of methods and questions at play in studying the genomic population structure of our species: "variance partitioning" and "clustering analysis."

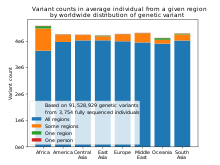

The results obtained from cluster analyses depend on several factors: Recent studies have been published using an increasing number of genetic markers.

[73] Genetic distance may be the result of physical boundaries restricting gene flow such as islands, deserts, mountains or forests.

[76] Pearse & Crandall 2004 wrote that FST figures cannot distinguish between a situation of high migration between populations with a long divergence time, and one of a relatively recent shared history but no ongoing gene flow.

They conclude: "In sum, we concur with Lewontin's conclusion that Western-based racial classifications have no taxonomic significance, and we hope that this research, which takes into account our current understanding of the structure of human diversity, places his seminal finding on firmer evolutionary footing.

"[78] Anthropologists (such as C. Loring Brace),[79] philosopher Jonathan Kaplan and geneticist Joseph Graves[80] have argued that while it is possible to find biological and genetic variation roughly corresponding to race, this is true for almost all geographically distinct populations: the cluster structure of genetic data is dependent on the initial hypotheses of the researcher and the populations sampled.

Cavalli-Sforza and colleagues argue that if genetic variations are investigated, they often correspond to population migrations due to new sources of food, improved transportation or shifts in political power.

The 3,636 subjects, from the United States and Taiwan, self-identified as belonging to white, African American, East Asian or Hispanic ethnic groups.

The study found "nearly perfect correspondence between genetic cluster and SIRE for major ethnic groups living in the United States, with a discrepancy rate of only 0.14 percent".

As a result, skin color differences within the population are not gradual, and there are relatively weak associations between self-reported race and African ancestry.

Loosely speaking, it is these small discontinuous jumps in genetic distance—across oceans, the Himalayas, and the Sahara—that provide the basis for the ability of STRUCTURE to identify clusters that correspond to geographic regions.

Thus, ancient geographic ancestry, which is highly correlated with self-identified race/ethnicity—as opposed to current residence—is the major determinant of genetic structure in the U.S.

This suggests that the Duffy negative genotype evolved in Sub-Saharan Africa and was subsequently positively selected for in the Malaria endemic zone.

"[102] Lorusso and Bacchini[6] argue that self-identified race is of greater use in medicine as it correlates strongly with risk-related exposomes that are potentially heritable when they become embodied in the epigenome.

They also cite evidence that this process can work positively – for example, the psychological advantage of perceiving oneself at the top of a social hierarchy is linked to improved health.

There are also methodological critics who reject racial naturalism because of concerns relating to the experimental design, execution, or interpretation of the relevant population-genetic research.

Spencer states that in order to accurately capture real biological entities, social factors must also be considered.

[111] Troy Duster points out that genetics is often not the predominant determinant of disease susceptibilities, even though they might correlate with specific socially defined categories.

He cites data collected by King and Rewers that indicates how dietary differences play a significant role in explaining variations of diabetes prevalence between populations.

Governmental provision of free relatively high-fat food to alleviate the prevalence of poverty in the population is noted as an explanation of this phenomenon.

From this, Lorusso and Bacchini conclude that the accuracy in the prediction of genetic ancestry on the basis of self-identification is low, specifically in racially admixed populations born out of complex ancestral histories.