Race to the Sea

Erich von Falkenhayn, Chief of the German General Staff (Oberste Heeresleitung OHL) since 14 September, concluded that a decisive victory could not be achieved on the Western Front and that it was equally unlikely in the east.

Over the winter lull, the French army established the theoretical basis of offensive trench warfare, originating many of the methods which became standard for the rest of the war.

Infiltration tactics, in which dispersed formations of infantry were followed by nettoyeurs de tranchée (trench cleaners), to capture by-passed strong points were promulgated.

Alfred von Schlieffen, Chief of the Imperial German General Staff, Oberste Heeresleitung (OHL) from 1891–1906, devised plans to evade the French frontier fortifications with an offensive on the flank, which would have a local numerical superiority and obtain rapidly a decisive victory.

Further west the Fifth Army had concentrated on the Sambre by 20 August, facing north either side of Charleroi and east towards the Belgian Fortified Position of Namur.

Next day General Paul von Hindenburg was appointed Oberbefehlshaber der gesamten Deutschen Streitkräfte im Osten (Ober Ost, Commander-in-Chief of German Armies in the Eastern Theatre).

Overnight, the IV Reserve Corps withdrew to a better position 6.2 mi (10 km) east and French air reconnaissance observed German forces moving north to face the Sixth Army.

The BEF advanced from 6–8 September, crossed the Petit Morin, captured bridges over the Marne and established a bridgehead 5.0 mi (8 km) deep.

The plan was cancelled soon afterwards, when Oberst (Colonel) Gerhard Tappen (OHL Operations Branch), reported from a tour of inspection at the front that the French were too exhausted to begin an offensive, that a final push would be decisive and that more withdrawals would compromise the morale of the German troops, after the defeat on the Marne.

As news reached Joffre that two German corps were moving south from Antwerp, the Sixth Army was forced to end its advance and dig in around Nampcel and Roye.

[47] On 21 September, Falkenhayn decided to concentrate the 6th Army near Amiens, to attack westwards to the coast and then envelop the French northern flank south of the Somme.

[48] The German II Bavarian and XIV Reserve corps pushed back a French Territorial division from Bapaume and advanced towards Bray-sur-Somme and Albert.

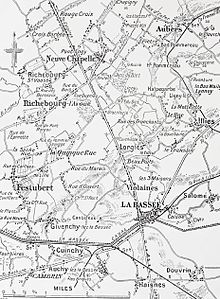

[50] By 4 October, German troops had also reached Givenchy-en-Gohelle and on the right flank of the French further south, the Territorial divisions were separated from X Corps, prompting Castelnau and Maud'huy to recommend a retreat.

[57] On 12 October, II Corps attacked to reach Givenchy and Pont du Hem, 3.7 mi (6 km) north of La Bassée Canal.

[58] From 14 to 15 October, II Corps attacked eastwards up La Bassée Canal and managed short advances on the flanks, with help from French cavalry but lost 967 casualties.

By 21 October, II Corps was ordered to dig in from the canal near Givenchy to Violaines, Illies, Herlies and Riez, while offensive operations continued to the north.

The cavalry was ordered to cross the Lys between Armentières and Menin as the III Corps advanced north-east to gain touch with the 7th Division near Ypres.

Kemmel, about 400 ft (120 m) above sea level, with spurs running south across the British line of advance, occupied by the German IV Cavalry Corps with three divisions.

A corps attack from La Couronne to Fontaine Houck began at 2:00 p.m. in wet and misty weather and by evening had captured Outtersteene and Méteren, at a cost of 708 casualties.

On the right, French cavalry attempted to support the attack but without howitzers, could not advance in level terrain, dotted with cottages used as improvised strong points.

The German defenders slipped away from defences in front of houses, hedges and walls, well sighted to keep the soldiers invisible, dug earth having been scattered rather than used for a parapet, which would have been visible.

Rain and mist made air reconnaissance impossible on 14 October but patrols found that the Germans had fallen back beyond Bailleul and crossed the Lys.

III Corps closed up to the river at Sailly, Bac St. Maur, Erquinghem and Pont de Nieppe, linking with the cavalry at Romarin.

On 16 October, the British secured the Lys crossings and late in the afternoon, German attacks began at Diksmuide and the next day the III Corps occupied Armentières.

By the end of the First Battle of Ypres both sides were exhausted, short of ammunition and suffering from collapses in morale and refusals of orders by some infantry units.

A moving barrage of fire was proposed as a combination of both methods and became a standard practice later in the war as guns and ammunition were accumulated in sufficient quantity.

[68] Falkenhayn issued memoranda on 7 and 25 January 1915, defining a theory of defensive warfare to be used on the Western Front, intended to enable ground to be held with the fewest possible troops.

The building of the new defences took until the autumn of 1915 and confronted Franco-British offensives with an evolving system of field fortifications, which was able to absorb the increasing power and sophistication of breakthrough attempts.

By 26 October, the Belgian Commander General Félix Wielemans, had decided to retreat but French objections and orders from King Albert led to a withdrawal being cancelled.

The Germans took ground on the Menin road on 29 October and drove back the British cavalry next day, to a line 1.9 mi (3 km) from Ypres.