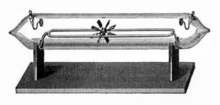

Crookes tube

It was used by Crookes, Johann Hittorf, Julius Plücker, Eugen Goldstein, Heinrich Hertz, Philipp Lenard, Kristian Birkeland and others to discover the properties of cathode rays, culminating in J. J. Thomson's 1897 identification of cathode rays as negatively charged particles, which were later named electrons.

Geissler tubes had only a low vacuum, around 10−3 atm (100 Pa),[6] and the electrons in them could only travel a short distance before hitting a gas molecule.

So the current of electrons moved in a slow diffusion process, constantly colliding with gas molecules, never gaining much energy.

By the 1870s, William Crookes (among other researchers) was able to evacuate his tubes to a lower pressure, 10−6 to 5x10−8 atm, using an improved Sprengel mercury vacuum pump invented by his coworker Charles A.

[citation needed] He found that as he pumped more air out of his tubes, a dark area in the glowing gas formed next to the cathode.

[7] What was happening was that as more air was pumped out of the tube, there were fewer gas molecules to obstruct the motion of the electrons from the cathode, so they could travel a longer distance, on average, before they struck one.

By the time the inside of the tube became dark, they were able to travel in straight lines from the cathode to the anode, without a collision.

They were accelerated to a high velocity by the electric field between the electrodes, both because they did not lose energy to collisions, and also because Crookes tubes were operated at a higher voltage.

[9] At the time, atoms were the smallest particles known and were believed to be indivisible, the electron was unknown, and what carried electric currents was a mystery.

During the last quarter of the 19th century, many ingenious types of Crookes tubes were invented and used in historic experiments to determine what cathode rays were.

[10] The debate was resolved in 1897 when J. J. Thomson measured the mass to charge ratio of the cathode rays, showing they were made of particles, but were around 1800 times lighter than the lightest atom, hydrogen.

[11] It was quickly realized that these particles were also responsible for electric currents in wires, and carried the negative charge in the atom.

The colorful glowing tubes were also popular in public lectures to demonstrate the mysteries of the new science of electricity.

Both the energy and the quantity of cathode rays produced depended on the pressure of residual gas in the tube.

On November 8, 1895, Wilhelm Röntgen was operating a Crookes tube covered with black cardboard when he noticed that a nearby fluorescent screen glowed faintly.

Röntgen began to investigate the rays full-time, and on December 28, 1895, published the first scientific research paper on X-rays.

The cathode had a concave spherical surface which focused the electrons into a small spot around 1 mm in diameter on the anode, in order to approximate a point source of X-rays, which gave the sharpest radiographs.

The Crookes tubes require a small amount of air in them to function, from about 10−6 to 5×10−8 atmosphere (7×10−4 - 4×10−5 torr or 0.1-0.006 pascal).

When they strike it, they knock large numbers of electrons out of the surface of the metal, which in turn are repelled by the cathode and attracted to the anode or positive electrode.

Later on, researchers painted the inside back wall of the tube with a phosphor, a fluorescent chemical such as zinc sulfide, in order to make the glow more visible.

The full details of the action in a Crookes tube are complicated, because it contains a nonequilibrium plasma of positively charged ions, electrons, and neutral atoms which are constantly interacting.

During the last quarter of the 19th century Crookes tubes were used in dozens of historic experiments to try to find out what cathode rays were.

[20] There were two theories: British scientists Crookes and Cromwell Varley believed they were particles of 'radiant matter', that is, electrically charged atoms.

German researchers E. Wiedemann, Heinrich Hertz, and Eugen Goldstein believed they were 'aether vibrations', some new form of electromagnetic waves, and were separate from what carried the current through the tube.

Julius Plücker in 1869 built a tube with an anode shaped like a Maltese Cross facing the cathode.

Heinrich Hertz built a tube with a second pair of metal plates to either side of the cathode ray beam, a crude CRT.

He did not find any bending, but it was later determined that his tube was insufficiently evacuated, causing accumulations of surface charge which masked the electric field.

Since the atoms are thousands of times more massive than the electrons, they move much slower, accounting for the lack of Doppler shift.