Raid on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby

[2] It was also believed that two British battlecruisers—which would be the fast ships sent out first to investigate any attack—had been despatched to South America and had taken part in the Battle of the Falkland Islands.

Sufficient information had been gleaned on the evening of 14 December to know that the German battlecruiser squadron would shortly be leaving port but did not suggest that all of the High Seas Fleet might be involved.

[5] Admiral John Jellicoe, commanding the Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow, was ordered to despatch the 1st Battlecruiser Squadron (Vice-Admiral David Beatty), with HMS Lion, Queen Mary, Tiger and New Zealand, together with the 2nd Battle Squadron (Vice-Admiral Sir George Warrender) comprising the modern dreadnoughts HMS King George V, Ajax, Centurion, Orion, Monarch and Conqueror, with the 1st Light Cruiser Squadron (Commodore William Goodenough) commanding HMS Southampton, Birmingham, Falmouth and Nottingham.

[6] Commodore Reginald Tyrwhitt at Harwich was ordered to sea with his light cruisers, HMS Aurora and Undaunted and 42 destroyers.

Commodore Roger Keyes was ordered to send eight submarines and his two command destroyers, HMS Lurcher and Firedrake, to take station off the island of Terschelling, to catch the German ships should they turn west into the English Channel.

[7] The remaining ships divided, Seydlitz, Blücher and Moltke proceeded towards Hartlepool, while Derfflinger, Von der Tann and Kolberg approached Scarborough.

At 08:15, Kolberg began to lay mines off Flamborough Head in a line extending 10 mi (8.7 nmi) out to sea.

The German ships were at such short range that the shell fuzes did not have time to set and many failed to explode or ricocheted into the town, because they were travelling horizontally, rather than plunging.

The submarine HMS C9 followed Patrol to sea but had to dive when shells started falling around it and at 08:50, the German ships departed.

[12] The ships had already departed when Patrol was clear of the harbour; Commodore Roger Keyes commented afterwards, that a target of three stationary cruisers was exactly what the submarine had been intended to attack.

The bad weather meant that he could not take destroyers with him but Beatty brought seven when he departed from Cromarty at 06:00, together with the battlecruiser squadron.

At 07:40 Jones, attempting to close on Roon to fire torpedoes, discovered that she was accompanied by two other cruisers and was obliged to withdraw at full speed.

At 07:55, he managed to make contact and Beatty sent New Zealand, his nearest ship, followed by the three light cruisers, spaced 2 mi (1.7 nmi) apart, to maximise their chance of spotting the enemy, followed by the remaining battlecruisers.

The chase of Roon, which might have led to an encounter with the main German fleet, was abandoned and the British squadron turned north to intercept Hipper.

On inquiring where the High Seas Fleet was, he discovered that it had returned home and that his destroyers had sighted British ships.

The two remaining British light cruisers moved off to assist but Beatty, not having been informed of the larger force, called one of them back.

Due to confused signalling, the first cruiser misunderstood the message flashed by searchlight, passed it on to the others and all four disengaged and turned back to Beatty.

Warrender also saw the ships and ordered Pakenham to give chase with the four armoured cruisers but these were too slow and the Germans disappeared again into the mist.

He abandoned the northern exit of the minefield and moved east and then south, attempting to position his ships to catch the German battlecruisers, should they slip past the slower British battleships.

Hipper initially attempted to catch up with his cruisers and come to their aid but once they reported the presence of British battleships to the south and that they had slipped past, he turned north to avoid them.

[25] Keyes's submarines had been despatched to find returning German ships and also failed, although one torpedo was fired at SMS Posen by HMS E11, which missed.

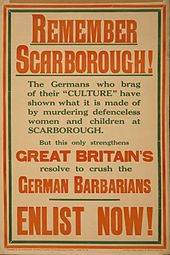

[26] The raid caused a great scandal in Britain, became a rallying cry against Germany for its attack upon civilians and against the Royal Navy for failing to prevent it.

The attack became part of a British propaganda campaign; 'Remember Scarborough' was used on army recruitment posters and editorials in neutral America condemned it; "This is not warfare, this is murder".

[27] At first, blame for the light cruisers disengaging from the German ships fell upon the commander, Goodenough, but the action was contrary to his record.

Jellicoe resolved that the entire Grand Fleet would be involved from the start in similar operations and the battlecruisers were moved to Rosyth to be closer.

The Kaiser reprimanded his admirals for their failure to capitalise upon an opportunity but made no changes to the orders restricting the fleet, which were largely responsible for Ingenohl's decisions.

[30][31] The German ships fired 1,150 shells into Hartlepool, striking targets including the steelworks, gasworks, railways, seven churches and 300 houses.