George Stephenson

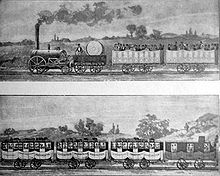

Pioneered by Stephenson, rail transport was one of the most important technological inventions of the 19th century and a key component of the Industrial Revolution.

George realised the value of education and paid to study at night school to learn reading, writing and arithmetic – he was illiterate until the age of 18.

A month before Davy presented his design to the Royal Society, Stephenson demonstrated his own lamp to two witnesses by taking it down Killingworth Colliery and holding it in front of a fissure from which firedamp was issuing.

Realizing this, he made a point of educating his son Robert in a private school, where he was taught to speak in Standard English with a Received Pronunciation accent.

A six-wheeled locomotive was built for the Kilmarnock and Troon Railway in 1817 but was withdrawn from service because of damage to the cast-iron rails.

[14] Another locomotive was supplied to Scott's Pit railroad at Llansamlet, near Swansea, in 1819 but it too was withdrawn, apparently because it was under-boilered and again caused damage to the track.

For the Stockton and Darlington Railway Stephenson used wrought-iron malleable rails that he had found satisfactory, notwithstanding the financial loss he suffered by not using his own patented design.

The 25-mile (40 km) railway connected collieries near Bishop Auckland to the River Tees at Stockton, passing through Darlington on the way.

[8] On an early trade card, Robert Stephenson & Co was described as "Engineers, Millwrights & Machinists, Brass & Iron Founders".

Wrought-iron rails could be produced in longer lengths than cast-iron and were less liable to crack under the weight of heavy locomotives.

The revised alignment presented the problem of crossing Chat Moss, an apparently bottomless peat bog, which Stephenson overcame by unusual means, effectively floating the line across it.

[8] The method he used was similar to that used by John Metcalf who constructed many miles of road across marshes in the Pennines, laying a foundation of heather and branches, which became bound together by the weight of the passing coaches, with a layer of stones on top.

As the L&MR approached completion in 1829, its directors arranged a competition to decide who would build its locomotives, and the Rainhill Trials were run in October 1829.

One significant innovation, suggested by Henry Booth, treasurer of the L&MR, was the use of a fire-tube boiler, invented by French engineer Marc Seguin that gave improved heat exchange.

[8] The opening ceremony of the L&MR, on 15 September 1830, drew luminaries from the government and industry, including the Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington.

[20] It required the structure to be constructed as two flat planes (overlapping in this case by 6 ft (1.8 m)) between which the stonework forms a parallelogram shape when viewed from above.

Realising the potential and need for the rail link Stephenson himself invested £2,500 and raised the remaining capital through his network of connections in Liverpool.

During this same period the Snibston estate in Leicestershire came up for auction, it lay adjoining the proposed Swannington to Leicester route and was believed to contain valuable coal reserves.

Stephenson realising the financial potential of the site, given its proximity to the proposed rail link and the fact that the manufacturing town of Leicester was then being supplied coal by canal from Derbyshire, bought the estate.

Employing a previously used method of mining in the midlands called tubbing to access the deep coal seams, his success could not have been greater.

[22][page needed] The next ten years were the busiest of Stephenson's life as he was besieged with requests from railway promoters.

Stephenson's conservative views on the capabilities of locomotives meant he favoured circuitous routes and civil engineering that were more costly than his successors thought necessary.

By this time he had settled into semi-retirement, supervising his mining interests in Derbyshire – tunnelling for the North Midland Railway revealed coal seams, and Stephenson put money into their exploitation.

George first courted Elizabeth (Betty) Hindmarsh, a farmer's daughter from Black Callerton, whom he met secretly in her orchard.

[24] On 11 January 1848,[25] at St Chad's Church in Shrewsbury, Shropshire,[26][27] George married for the third time, to Ellen Gregory, another farmer's daughter originally from Bakewell in Derbyshire, who had been his housekeeper.

Seven months after his wedding, George contracted pleurisy and died, aged 67, at noon on Saturday 12 August 1848 at Tapton House in Chesterfield, Derbyshire.

Britain led the world in the development of railways which acted as a stimulus for the Industrial Revolution by facilitating the transport of raw materials and manufactured goods.

At the event a full-size working replica of the Rocket was on show, which then spent two days on public display at the Chesterfield Market Festival.

Stephenson's face is shown alongside an engraving of the Rocket steam engine and the Skerne Bridge on the Stockton to Darlington Railway.

[41] Harry Turtledove's alternate history short story "The Iron Elephant" depicts a race between a newly invented steam engine and a mammoth-drawn train in 1782.