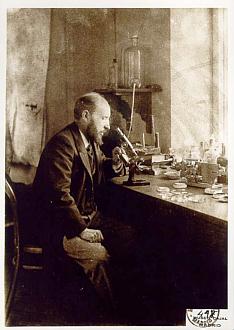

Santiago Ramón y Cajal

[14]: 156 John Brande Trend wrote in 1965 that Ramón y Cajal "was a liberal in politics, an evolutionist in philosophy, an agnostic in religion".

In addition to being a regenerationist, Ramón y Cajal is considered a Spanish nationalist and centralist,[19] and in this sense he interprets non-Spanish nationalisms, such as Catalan and Basque, describing them as separatist.

[21] He discovered the axonal growth cone, and demonstrated experimentally that the relationship between nerve cells was not continuous, or a single system as per then extant reticular theory, but rather contiguous;[6] there were gaps between neurons.

This provided definitive evidence for what Heinrich Waldeyer would name "neuron theory", now widely considered the foundation of modern neuroscience.

[6] He is also considered by some to be the first "neuroscientist" since in 1894 he stated to the Royal Society of London: "The ability of neurons to grow in an adult and their power to create new connections can explain learning."

He was a proponent of polarization of nerve cell function and his student, Rafael Lorente de Nó, would continue this study of input-output systems into cable theory and some of the earliest circuit analysis of neural structures.

[7] The most famous distinction he was awarded was the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1906, together with the Italian scientist Camillo Golgi "in recognition of their work on the structure of the nervous system".

[7] This caused some controversy because Golgi, a staunch supporter of reticular theory, disagreed with Ramón y Cajal in his view of the neuron doctrine.

[30] Ramón y Cajal was an International Member of both the United States National Academy of Sciences and the American Philosophical Society.

[33] Cajal posed for a statue that was created by the sculptor Mariano Benlliure and was installed in 1924 in the Paraninfo building at the School of Medicine of the University of Zaragoza.

This full-body statue stands 3 meters (around 10 ft) high on a narrow pedestal and was created by Lorenzo Domínguez,[34] a Chilean medical student.

1982 a TV mini series was created in Spain titled Ramón y Cajal: Historia de una voluntad.

Exhibition curators and contributing authors to the catalog include: Santiago Ramón y Cajal Junquera, Miguel Ángel Freire Mallo, Paloma Esteban Leal, Pablo García, Virginia G. Marin, Ma Cruz Osuna, Isabel Argerich Fernández, Paloma Calle, Marta C. Lopera, Ricardo Martínez, Pilar Sedano Espín, Eugenia Gimeno Pascual, Sonia Tortajada, and Juan Antonio Sáez Dégano.

[38] In 2014, the National Institutes of Health initiated an ongoing exhibition of original Ramón y Cajal drawings in the John Porter Neuroscience Research Center, located in the NIH central campus in Bethesda, MD, USA.

[39] The exhibition also includes contemporary artwork curated by Jeff Diamond, which was created by artists Rebecca Kamen and Dawn Hunter.

[46] From January 31 – May 29, 2016, Cajal's work was featured in the inaugural exhibition for the re-opening of University of California's Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive Architecture of Life.

Keynote speaker Dr. Rafael Yuste was honored at a reception held at the Spanish Ambassador's, Ramón Gil-Casares, home.

Dawn Hunter's Cajal Inventory art project was exhibited at the symposium for the general public in the institute's library.

[48] Every year since 2001, more than two hundred postdoctoral scholarships are awarded by the Spanish Ministry of Science to middle career scholars from different fields of knowledge.

[49] An exhibition called The Beautiful Brain: The Drawings of Santiago Ramón y Cajal travelled through North America, beginning 2017 in the US at the Weisman Art Museum in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

[60] In 2017, UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) recognised Cajal's Legacy (which had been kept in a museum from 1945 to 1989) as a World Heritage treasure.