Rancidification

Rancidification is the process of complete or incomplete autoxidation or hydrolysis of fats and oils when exposed to air, light, moisture, or bacterial action, producing short-chain aldehydes, ketones and free fatty acids.

[3] Similar to rancidification, oxidative degradation also occurs in other hydrocarbons, such as lubricating oils, fuels, and mechanical cutting fluids.

[4] Five pathways for rancidification are recognized:[5] Hydrolytic rancidity refers to the odor that develops when triglycerides are hydrolyzed and free fatty acids are released.

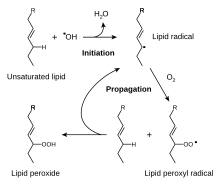

[7] A double bond of an unsaturated fatty acid can be oxidised by oxygen from the air in reactions catalysed by plant or animal lipoxygenase enzymes,[6] producing a hydroperoxide as a reactive intermediate, as in free-radical peroxidation.

Microbial rancidity refers to a water-dependent process in which microorganisms, such as bacteria or molds, use their enzymes such as lipases to break down fat.

[8][9] Animal studies show evidence of organ damage, inflammation, carcinogenesis, and advanced atherosclerosis, although typically the dose of oxidized lipids is larger than what would be consumed by humans.

The effectiveness of water-soluble antioxidants is limited in preventing direct oxidation within fats, but is valuable in intercepting free radicals that travel through the aqueous parts of foods.

Antimicrobial agents can also delay or prevent rancidification by inhibiting the growth of bacteria or other micro-organisms that affect the process.

Over time, the Rancimat method has become established, and it has been accepted into a number of national and international standards, for example AOCS Cd 12b-92 and ISO 6886.