Rani of Jhansi

When the Maharaja died in 1853, the British East India Company under Governor-General Lord Dalhousie refused to recognize the claim of his adopted heir and annexed Jhansi under the Doctrine of Lapse.

The Rani managed to escape on horseback and joined the rebels in capturing Gwalior, where they proclaimed Nana Saheb as Peshwa of the revived Maratha Empire.

[2] In the city of Varanasi, he and his wife Bhagirathi had a daughter, who they named Manakarnika, an epithet of the River Ganges; in childhood she was known by the diminutive Manu.

[5] According to uncorroborated popular legend, her childhood playmates in Bithur included Nana Sahib and Tatya Tope, who would similarly become prominent in 1857.

These stories relate that Manakarnika, deprived of a feminine influence by her mother's death, was allowed to play and learn with her male playmates: she was literate, skilled in horseriding, and—extremely unusually for a girl, if true—was given lessons in fencing, swordplay, and even firearms.

[9] According to popular legend, he turned blind eye to Rani Lakshmibhai's equipping and training of an armed all-female regiment, but if it existed, it was likely formed after Gangadhar Rao's death.

[11] The East India Company administration, led by Governor-General Lord Dalhousie, had for several years enforced a "doctrine of lapse", wherein Indian states whose Hindu rulers died without a natural heir were annexed by Britain.

She initiated coversations with Major Ellis, a sympathetic local Company official, and engaged John Lang, an Australian lawyer, to represent her.

[21] She disagreed with the Company in the following years over various matters: on taxation and debts, the 1854 lifting of the ban on cattle slaughter in Jhansi, the British occupation of a temple outside the town, and of course the continued foreign rule.

Nana Sahib organised massacres of the British at Kanpur, while similar events occurred in Lucknow; news of these killings had not reached Jhansi by the end of May.

[29] On 8 June, the British surrendered and asked for safe passage; after an unknown someone acquiesced, they were led to the Jokhan Bagh garden, where nearly all of them were killed.

S. Thornton, a tax collector in Samthar State, wrote that the Rani had instigated the revolt, while two somewhat questionable eyewitness accounts reported that she executed three British messengers and gave the rest false promise of safe passage.

[32] Lakshmibai herself claimed, in two mid-June letters to Major Erskine, commissioner of the Saugor division, that she had been at the mercy of the mutineers and could not help the besieged British.

This skirmish led the Rani to focus on re-establishing military authority, and so she ordered the recruitment of troops and the manufacturing of cannon and other weapons.

[36] With this larger force of approximately 15,000 troops, Jhansi saw off an attack by nearby Orchha, who had remained loyal to the Company and whose leaders judged that the British would turn a blind eye to the war.

Orchha invaded on 10 August and besieged Jhansi from early September to late October, when they were driven off by the raja of Banpur's troops.

[37] In September 1857, with Jhansi under Orchha siege, the Rani requested that Major Erskine send forces to help, as he had earlier promised when authorizing her rule.

This encouraged the Rani, who was still of two minds: she continued to send unanswered conciliations to the British, while at the same time militantly preparing arms and ammunition.

Their attention now fell on the remaining pockets of resistance in Central India: Jhansi, a pivotal strategic location and the home of a ruler now seen as a "Jezebel", was a prime target.

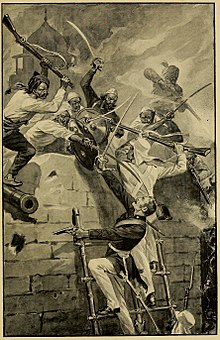

Reconnaissance found that not only were the defences in excellent condition, with 25-foot (7.6 m) loopholed granite walls topped by large guns and batteries able to enfilade each other, but the surrounding countryside had been removed of all cover and foliage.

Rose was making preparations for an assault when news reached him that the Rani's childhood friend Tatya Tope was marching to rescue Jhansi with more than 20,000 men.

[57] On 17 June in Kotah-ki-Serai near the Phool Bagh of Gwalior, a squadron of the 8th (King's Royal Irish) Hussars, under Captain Heneage, fought the large Indian force commanded by Rani Lakshmibai, who was trying to leave the area.

In this engagement, according to an eyewitness account, Rani Lakshmibai put on a sowar's uniform and attacked one of the hussars; she was unhorsed and also wounded, probably by his sabre.

[59][60] According to another tradition Rani Lakshmibai, the Queen of Jhansi, dressed as a cavalry leader, was badly wounded; not wishing the British to capture her body, she told a hermit to burn it.

In the British report of this battle, Hugh Rose commented that Rani Lakshmibai is "personable, clever and beautiful" and she is "the most dangerous of all Indian leaders".

The regiment was named in honor of Rani Lakshmibai, the warrior queen of Jhansi who fought against British colonial rule in India in 1857.

The women were trained in military tactics, physical fitness, and marksmanship, and were deployed in Burma and other parts of Southeast Asia to fight against the British.

[65] A popular stanza from it reads: बुंदेले हरबोलों के मुँह हमने सुनी कहानी थी, खूब लड़ी मर्दानी वह तो झाँसी वाली रानी थी।।[66]Translation: "From the Bundele Harbolas' mouths we heard stories / She fought like a man, she was the Rani of Jhansi.

"[67] For Marathi people, there is an equally well-known ballad about the brave queen penned at the spot near Gwalior where she died in battle, by B. R. Tambe, who was a poet laureate of Maharashtra and of her clan.