Rayleigh wave

They can be produced in materials in many ways, such as by a localized impact or by piezo-electric transduction, and are frequently used in non-destructive testing for detecting defects.

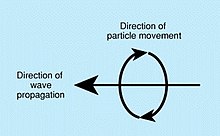

Rayleigh waves include both longitudinal and transverse motions that decrease exponentially in amplitude as distance from the surface increases.

In addition, the motion amplitude decays and the eccentricity changes as the depth into the material increases.

The depth of significant displacement in the solid is approximately equal to the acoustic wavelength.

[1] The typical speed of Rayleigh waves in metals is of the order of 2–5 km/s, and the typical Rayleigh speed in the ground is of the order of 50–300 m/s for shallow waves less than 100-m depth and 1.5–4 km/s at depths greater than 1 km.

Since Rayleigh waves are confined near the surface, their in-plane amplitude when generated by a point source decays only as

[5] Since this equation has no inherent scale, the boundary value problem giving rise to Rayleigh waves are dispersionless.

This means that the velocity of a Rayleigh wave in practice becomes dependent on the wavelength (and therefore frequency), a phenomenon referred to as dispersion.

[1] Rayleigh waves on ideal, homogeneous and flat elastic solids show no dispersion, as stated above.

However, if a solid or structure has a density or sound velocity that varies with depth, Rayleigh waves become dispersive.

This occurs because a Rayleigh wave of lower frequency has a relatively long wavelength.

It is also possible to observe Rayleigh wave dispersion in thin films or multi-layered structures.

Rayleigh waves are widely used for materials characterization, to discover the mechanical and structural properties of the object being tested – like the presence of cracking, and the related shear modulus.

They are used at different length scales because they are easily generated and detected on the free surface of solid objects.

Rayleigh waves propagating at high ultrasonic frequencies (10–1000 MHz) are used widely in different electronic devices.

Examples of electronic devices using Rayleigh waves are filters, resonators, oscillators, sensors of pressure, temperature, humidity, etc.

However, large earthquakes may generate Rayleigh waves that travel around the Earth several times before dissipating.

Rayleigh waves emanating outward from the epicenter of an earthquake travel along the surface of the earth at about 10 times the speed of sound in air (0.340 km/s), that is ~3 km/s.

The intensity of Rayleigh wave shaking at a particular location is dependent on several factors: Local geologic structure can serve to focus or defocus Rayleigh waves, leading to significant differences in shaking over short distances.

Low frequency Rayleigh waves generated during earthquakes are used in seismology to characterise the Earth's interior.

In intermediate ranges, Rayleigh waves are used in geophysics and geotechnical engineering for the characterisation of oil deposits.

These applications are based on the geometric dispersion of Rayleigh waves and on the solution of an inverse problem on the basis of seismic data collected on the ground surface using active sources (falling weights, hammers or small explosions, for example) or by recording microtremors.

Rayleigh ground waves are important also for environmental noise and vibration control since they make a major contribution to traffic-induced ground vibrations and the associated structure-borne noise in buildings.

Low frequency (< 20 Hz) Rayleigh waves are inaudible, yet they can be detected by many mammals, birds, insects and spiders.

Humans should be able to detect such Rayleigh waves through their Pacinian corpuscles, which are in the joints, although people do not seem to consciously respond to the signals.

After the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake, some people have speculated that Rayleigh waves served as a warning to animals to seek higher ground, allowing them to escape the more slowly traveling tsunami.

Other animal early warning systems may rely on an ability to sense infrasonic waves traveling through the air.