Reactor-grade plutonium

Generation II thermal-neutron reactors (today's most numerous nuclear power stations) can reuse reactor-grade plutonium only to a limited degree as MOX fuel, and only for a second cycle.

Fast-neutron reactors, of which there are a handful operating today with a half dozen under construction, can use reactor-grade plutonium fuel as a means to reduce the transuranium content of spent nuclear fuel/nuclear waste.

[12] These computations are theoretical and assume the non-trivial issue of dealing with the heat generation from the higher content of non-weapons usable Pu-238 could be overcome.)

As the premature initiation from the spontaneous fission of Pu-240 would ensure a low explosive yield in such a device, the surmounting of both issues in the construction of an Improvised nuclear device is described as presenting "daunting" hurdles for a Fat Man-era implosion design, and the possibility of terrorists achieving this fizzle yield being regarded as an "overblown" apprehension with the safeguards that are in place.

[13][7][14][15][16][17] Others disagree on theoretical grounds and state that while they would not be suitable for stockpiling or being emplaced on a missile for long periods of time, dependably high non-fizzle level yields can be achieved,[18][19][20][21][22][23] arguing that it would be "relatively easy" for a well funded entity with access to fusion boosting tritium and expertise to overcome the problem of pre-detonation created by the presence of Pu-240, and that a remote manipulation facility could be utilized in the assembly of the highly radioactive gamma ray emitting bomb components, coupled with a means of cooling the weapon pit during storage to prevent the plutonium charge contained in the pit from melting, and a design that kept the implosion mechanisms high explosives from being degraded by the pit's heat.

[18] No information available in the public domain suggests that any well funded entity has ever seriously pursued creating a nuclear weapon with an isotopic composition similar to modern, high burnup, reactor grade plutonium.

[31][32] Some information regarding this test was declassified in July 1977, under instructions from President Jimmy Carter, as background to his decision to prohibit nuclear reprocessing in the US.

[31] The initial codename for the Magnox reactor design amongst the government agency which mandated it, the UKAEA, was the Pressurised Pile Producing Power and Plutonium (PIPPA) and as this codename suggests, the reactor was designed as both a power plant and, when operated with low fuel "burn-up"; as a producer of plutonium-239 for the nascent nuclear weapons program in Britain.

This test detonation resulted in the creation of a low-yield fizzle explosion, producing an estimated yield of approximately 0.48 kilotons,[35] from an undisclosed isotopic composition.

[14] Likewise, the World Nuclear Association suggests that the US-UK 1962 test had at least 85% plutonium-239, a much higher isotopic concentration than what is typically present in the spent fuel from the majority of operating civilian reactors.

[39] In 2002 former Deputy Director General of the IAEA, Bruno Pelaud, stated that the DoE statement was misleading and that the test would have the modern definition of fuel-grade with a Pu-240 content of only 12%[40] In 1997 political analyst Matthew Bunn and presidential technology advisor John Holdren, both of the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, cited a 1990s official U.S. assessment of programmatic alternatives for plutonium disposition.

While it does not specify which RGPu definition is being referred to, it nonetheless states that "reactor-grade plutonium (with an unspecified isotopic composition) can be used to produce nuclear weapons at all levels of technical sophistication," and "advanced nuclear weapon states such as the United States and Russia, using modern designs, could produce weapons from "reactor-grade plutonium" having reliable explosive yields, weight, and other characteristics generally comparable to those of weapons made from weapon-grade plutonium"[41] In a 2008 paper, Kessler et al. used a thermal analysis to conclude that a hypothetical nuclear explosive device was "technically unfeasible" using reactor grade plutonium from a reactor that had a burn up value of 30 GWd/t using "low technology" designs akin to Fat Man with spherical explosive lenses, or 55 GWd/t for "medium technology" designs.

Though the "[reactor-grade]plutonium economy" it would generate, presently returns social distaste and varied arguments about proliferation-potential, in the public mindset.

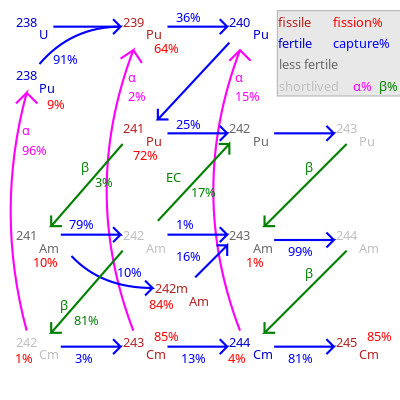

[56][note 2] Computations state that the energy yield of a nuclear explosive decreases by two orders of magnitude if the 240Pu content increases to 25%,(0.2 kt).

In 1977 the Carter administration placed a ban on reprocessing spent fuel, in an effort to set an international example, as within the US, there is the perception that it would lead to nuclear weapons proliferation.

[62] This decision has remained controversial and is viewed by many US physicists and engineers as fundamentally in error, having cost the US taxpayer and the fund generated by US reactor utility operators, with cancelled programs and the over 1 billion dollar investment into the proposed alternative, that of Yucca Mountain nuclear waste repository ending in protests, lawsuits and repeated stop-and-go decisions depending on the opinions of new incoming presidents.

Thus, physicists and engineers have pointed out, as hundreds/thousands of years pass, the alternative to fast reactor "burning" or recycling of the plutonium from the world fleet of reactors until it is all burnt up, the alternative to burning most frequently proposed, that of deep geological repository, such as Onkalo spent nuclear fuel repository, have the potential to become "plutonium mines", from which weapons-grade material for nuclear weapons could be acquired by simple PUREX extraction, in the centuries-to-millennia to come.

The RAND corporation suggested that their repeated experience of failure and being scammed has possibly led to terrorists concluding that nuclear acquisition is too difficult and too costly to be worth pursuing.