Number line

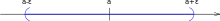

Wrapping the line into a circle relates modular arithmetic to the geometric composition of angles.

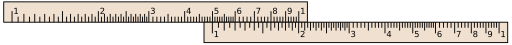

Marking the line with logarithmically spaced graduations associates multiplication and division with geometric translations, the principle underlying the slide rule.

In analytic geometry, coordinate axes are number lines which associate points in a geometric space with tuples of numbers, so geometric shapes can be described using numerical equations and numerical functions can be graphed.

The first mention of the number line used for operation purposes is found in John Wallis's Treatise of Algebra (1685).

[2] In his treatise, Wallis describes addition and subtraction on a number line in terms of moving forward and backward, under the metaphor of a person walking.

An earlier depiction without mention to operations, though, is found in John Napier's A Description of the Admirable Table of Logarithmes (1616), which shows values 1 through 12 lined up from left to right.

[3] Contrary to popular belief, René Descartes's original La Géométrie does not feature a number line, defined as we use it today, though it does use a coordinate system.

In particular, Descartes's work does not contain specific numbers mapped onto lines, only abstract quantities.

This is unnecessary, since according to the rules of geometry a line without endpoints continues indefinitely in the positive and negative directions.

One of the most common choices is the logarithmic scale, which is a representation of the positive numbers on a line, such that the distance of two points is the unit length, if the ratio of the represented numbers has a fixed value, typically 10.

This approach is useful, when one wants to represent, on the same figure, values with very different order of magnitude.

For example, one requires a logarithmic scale for representing simultaneously the size of the different bodies that exist in the Universe, typically, a photon, an electron, an atom, a molecule, a human, the Earth, the Solar System, a galaxy, and the visible Universe.

Together these lines form what is known as a Cartesian coordinate system, and any point in the plane represents the value of a pair of real numbers.

Further, the Cartesian coordinate system can itself be extended by visualizing a third number line "coming out of the screen (or page)", measuring a third variable called z.

Then any point in the three-dimensional space that we live in represents the values of a trio of real numbers.

It is a theorem that any linear continuum with a countable dense subset and no maximum or minimum element is order-isomorphic to the real line.

In order theory, the famous Suslin problem asks whether every linear continuum satisfying the countable chain condition that has no maximum or minimum element is necessarily order-isomorphic to R. This statement has been shown to be independent of the standard axiomatic system of set theory known as ZFC.

As a locally compact space, the real line can be compactified in several different ways.

The one-point compactification of R is a circle (namely, the real projective line), and the extra point can be thought of as an unsigned infinity.

There is also the Stone–Čech compactification of the real line, which involves adding an infinite number of additional points.

of subspace V. In this way the real line consists of the fixed points of the conjugation.

Note the logarithmic scale markings on each of the axes, and that the log x and log y axes (where the logarithms are 0) are where x and y themselves are 1.