Irrational number

[3] The first proof of the existence of irrational numbers is usually attributed to a Pythagorean (possibly Hippasus of Metapontum),[4] who probably discovered them while identifying sides of the pentagram.

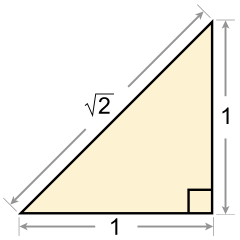

[5] The Pythagorean method would have claimed that there must be some sufficiently small, indivisible unit that could fit evenly into one of these lengths as well as the other.

Hippasus in the 5th century BC, however, was able to deduce that there was no common unit of measure, and that the assertion of such an existence was a contradiction.

Whatever the consequence to Hippasus himself, his discovery posed a very serious problem to Pythagorean mathematics, since it shattered the assumption that numbers and geometry were inseparable; a foundation of their theory.

The discovery of incommensurable ratios was indicative of another problem facing the Greeks: the relation of the discrete to the continuous.

This was brought to light by Zeno of Elea, who questioned the conception that quantities are discrete and composed of a finite number of units of a given size.

He sought to prove this by formulating four paradoxes, which demonstrated the contradictions inherent in the mathematical thought of the time.

While Zeno's paradoxes accurately demonstrated the deficiencies of contemporary mathematical conceptions, they were not regarded as proof of the alternative.

The next step was taken by Eudoxus of Cnidus, who formalized a new theory of proportion that took into account commensurable as well as incommensurable quantities.

A magnitude "...was not a number but stood for entities such as line segments, angles, areas, volumes, and time which could vary, as we would say, continuously.

"Eudoxus' theory enabled the Greek mathematicians to make tremendous progress in geometry by supplying the necessary logical foundation for incommensurable ratios".

[11] As a result of the distinction between number and magnitude, geometry became the only method that could take into account incommensurable ratios.

Also crucial to Zeno's work with incommensurable magnitudes was the fundamental focus on deductive reasoning that resulted from the foundational shattering of earlier Greek mathematics.

Theodorus of Cyrene proved the irrationality of the surds of whole numbers up to 17, but stopped there probably because the algebra he used could not be applied to the square root of 17.

[13] Geometrical and mathematical problems involving irrational numbers such as square roots were addressed very early during the Vedic period in India.

[16] Later, in their treatises, Indian mathematicians wrote on the arithmetic of surds including addition, subtraction, multiplication, rationalization, as well as separation and extraction of square roots.

He dealt with them freely but explains them in geometric terms as follows:[20] "It will be a rational (magnitude) when we, for instance, say 10, 12, 3%, 6%, etc., because its value is pronounced and expressed quantitatively.

[21] In the 10th century, the Iraqi mathematician Al-Hashimi provided general proofs (rather than geometric demonstrations) for irrational numbers, as he considered multiplication, division, and other arithmetical functions.

[23] The 17th century saw imaginary numbers become a powerful tool in the hands of Abraham de Moivre, and especially of Leonhard Euler.

The year 1872 saw the publication of the theories of Karl Weierstrass (by his pupil Ernst Kossak), Eduard Heine (Crelle's Journal, 74), Georg Cantor (Annalen, 5), and Richard Dedekind.

Weierstrass's method has been completely set forth by Salvatore Pincherle in 1880,[24] and Dedekind's has received additional prominence through the author's later work (1888) and the endorsement by Paul Tannery (1894).

Weierstrass, Cantor, and Heine base their theories on infinite series, while Dedekind founds his on the idea of a cut (Schnitt) in the system of all rational numbers, separating them into two groups having certain characteristic properties.

The subject has received later contributions at the hands of Weierstrass, Leopold Kronecker (Crelle, 101), and Charles Méray.

Continued fractions, closely related to irrational numbers (and due to Cataldi, 1613), received attention at the hands of Euler, and at the opening of the 19th century were brought into prominence through the writings of Joseph-Louis Lagrange.

[25] While Lambert's proof is often called incomplete, modern assessments support it as satisfactory, and in fact for its time it is unusually rigorous.

Later, Georg Cantor (1873) proved their existence by a different method, which showed that every interval in the reals contains transcendental numbers.

Charles Hermite (1873) first proved e transcendental, and Ferdinand von Lindemann (1882), starting from Hermite's conclusions, showed the same for π. Lindemann's proof was much simplified by Weierstrass (1885), still further by David Hilbert (1893), and was finally made elementary by Adolf Hurwitz[citation needed] and Paul Gordan.

Dov Jarden gave a simple non-constructive proof that there exist two irrational numbers a and b, such that ab is rational:[28][29] Although the above argument does not decide between the two cases, the Gelfond–Schneider theorem shows that

This is so because, by the formula relating logarithms with different bases, which we can assume, for the sake of establishing a contradiction, equals a ratio m/n of positive integers.

In fact, the irrationals equipped with the subspace topology have a basis of clopen groups so the space is zero-dimensional.