Real property

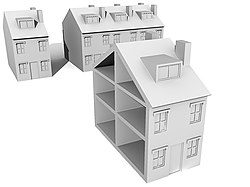

For a structure (also called an improvement or fixture) to be considered part of the real property, it must be integrated with or affixed to the land.

This includes crops, buildings, machinery, wells, dams, ponds, mines, canals, and roads.

Under European civil law, a lawsuit that seeks official recognition of a property right is known as an actio in rem (action in relation to a thing).

The distinction can be subtle; the medieval action of novel disseisin, although aimed at repossessing land, was not an actio in rem because it was brought against the alleged dispossessor.

[2][3] This view is not accepted in continental civil law, but can be understood in the context of legal developments during Bracton's lifetime.

Laws governing the conveyance of land and that of movable personal property then developed along different paths.

Houseboats, for example, occupy a gray area between personal and real property, and may be treated as either according to jurisdiction or circumstance.

The surrounding development and proximity, such as markets and transportation routes, will also determine the value of the real property.

Zoning regulations regarding multi-story development are modified to intensify the use of cities, instead of occupying more physical space.

Such a description usually makes use of natural or man-made boundaries such as seacoasts, rivers, streams, the crests of ridges, lakeshores, highways, roads, and railroad tracks or purpose-built markers such as cairns, surveyor's posts, iron pins or pipes, concrete monuments, fences, official government surveying marks (such as ones affixed by the National Geodetic Survey), and so forth.

In many cases, a description refers to one or more lots on a plat, a map of property boundaries kept in public records.

However, if TIC property is sold or subdivided, in some States, Provinces, etc., a credit can be automatically made for unequal contributions to the purchase price (unlike a partition of a JTWROS deed).

Some exceptions apply: for example, a farm owner in New Jersey employed several migrant workers who lived on the property during the harvest season.

[11] In the law of almost every country, the state is the ultimate owner of all land under its jurisdiction, because it is the sovereign, or supreme lawmaking authority.

This fact is material when, for example, the property has been disclaimed by its erstwhile owner, in which case the law of escheat applies.

Real property also includes many legal relationships between individuals or owners of the land that are purely conceptual.

Another is the various "incorporeal hereditaments", such as profits-à-Prendre, where an individual may have the right to take crops from land that is part of another's estate.

Things that are permanently attached to the land, which also can be referred to as improvements, include homes, garages, and buildings.

With the advent of industrialization, important new uses for land emerged as sites for factories, warehouses, offices, and urban agglomerations.

This resulted in a much-improved understanding of the: For an introduction to the economic analysis of property law, see Shavell (2004), and Cooter and Ulen (2003).

Ellickson (1993) broadens the economic analysis of real property with a variety of facts drawn from history and ethnography.