Multiplicative inverse

Multiplying by a number is the same as dividing by its reciprocal and vice versa.

For example, multiplication by 4/5 (or 0.8) will give the same result as division by 5/4 (or 1.25).

The term reciprocal was in common use at least as far back as the third edition of Encyclopædia Britannica (1797) to describe two numbers whose product is 1; geometrical quantities in inverse proportion are described as reciprocall in a 1570 translation of Euclid's Elements.

Multiplicative inverses can be defined over many mathematical domains as well as numbers.

The terminology difference reciprocal versus inverse is not sufficient to make this distinction, since many authors prefer the opposite naming convention, probably for historical reasons (for example in French, the inverse function is preferably called the bijection réciproque).

The property that every element other than zero has a multiplicative inverse is part of the definition of a field, of which these are all examples.

Thus, the two distinct notions of the inverse of a function are strongly related in this case, but they still do not coincide, since the multiplicative inverse of Ax would be (Ax)−1, not A−1x.

A ring in which every nonzero element has a multiplicative inverse is a division ring; likewise an algebra in which this holds is a division algebra.

As mentioned above, the reciprocal of every nonzero complex number

It can be found by multiplying both top and bottom of 1/z by its complex conjugate

, the absolute value of z squared, which is the real number a2 + b2: The intuition is that gives us the complex conjugate with a magnitude reduced to a value of

For example, additive and multiplicative inverses of i are −(i) = −i and 1/i = −i, respectively.

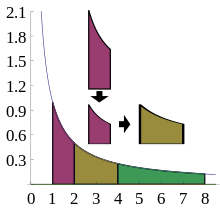

For a complex number in polar form z = r(cos φ + i sin φ), the reciprocal simply takes the reciprocal of the magnitude and the negative of the angle: In real calculus, the derivative of 1/x = x−1 is given by the power rule with the power −1: The power rule for integrals (Cavalieri's quadrature formula) cannot be used to compute the integral of 1/x, because doing so would result in division by 0:

The reciprocal may be computed by hand with the use of long division.

has a zero at x = 1/b, Newton's method can find that zero, starting with a guess

and iterating using the rule: This continues until the desired precision is reached.

For example, suppose we wish to compute 1/17 ≈ 0.0588 with 3 digits of precision.

Taking x0 = 0.1, the following sequence is produced: A typical initial guess can be found by rounding b to a nearby power of 2, then using bit shifts to compute its reciprocal.

In constructive mathematics, for a real number x to have a reciprocal, it is not sufficient that x ≠ 0.

In terms of the approximation algorithm described above, this is needed to prove that the change in y will eventually become arbitrarily small.

Its additive inverse is the only negative number that is equal to its reciprocal minus one:

The reciprocal function plays an important role in simple continued fractions, which have a number of remarkable properties relating to the representation of (both rational and) irrational numbers.

To see this, it is sufficient to multiply the equation xy = 0 by the inverse of x (on the left), and then simplify using associativity.

In the absence of associativity, the sedenions provide a counterexample.

The converse does not hold: an element which is not a zero divisor is not guaranteed to have a multiplicative inverse.

Within Z, all integers except −1, 0, 1 provide examples; they are not zero divisors nor do they have inverses in Z.

If the ring or algebra is finite, however, then all elements a which are not zero divisors do have a (left and right) inverse.

For, first observe that the map f(x) = ax must be injective: f(x) = f(y) implies x = y: Distinct elements map to distinct elements, so the image consists of the same finite number of elements, and the map is necessarily surjective.

Specifically, ƒ (namely multiplication by a) must map some element x to 1, ax = 1, so that x is an inverse for a.

A sequence of pseudo-random numbers of length q − 1 will be produced by the expansion.