Group (mathematics)

For example, the integers with the addition operation form an infinite group, which is generated by a single element called

The concept of a group was elaborated for handling, in a unified way, many mathematical structures such as numbers, geometric shapes and polynomial roots.

After contributions from other fields such as number theory and geometry, the group notion was generalized and firmly established around 1870.

, form a mathematical object belonging to a broad class sharing similar structural aspects.

Yet somehow hidden behind these axioms is the monster simple group, a huge and extraordinary mathematical object, which appears to rely on numerous bizarre coincidences to exist.

This reflects also an informal way of thinking: that the group is the same as the set except that it has been enriched by additional structure provided by the operation.

[9][10][11] The original motivation for group theory was the quest for solutions of polynomial equations of degree higher than 4.

The 19th-century French mathematician Évariste Galois, extending prior work of Paolo Ruffini and Joseph-Louis Lagrange, gave a criterion for the solvability of a particular polynomial equation in terms of the symmetry group of its roots (solutions).

Certain abelian group structures had been used implicitly in Carl Friedrich Gauss's number-theoretical work Disquisitiones Arithmeticae (1798), and more explicitly by Leopold Kronecker.

[17] In 1847, Ernst Kummer made early attempts to prove Fermat's Last Theorem by developing groups describing factorization into prime numbers.

[20] As of the 20th century, groups gained wide recognition by the pioneering work of Ferdinand Georg Frobenius and William Burnside (who worked on representation theory of finite groups), Richard Brauer's modular representation theory and Issai Schur's papers.

This project exceeded previous mathematical endeavours by its sheer size, in both length of proof and number of researchers.

[24] Group theory remains a highly active mathematical branch,[b] impacting many other fields, as the examples below illustrate.

However, only assuming the existence of a left identity and a right inverse (or vice versa) is not sufficient to define a group.

For example, Henri Poincaré founded what is now called algebraic topology by introducing the fundamental group.

Intertwining addition and multiplication operations yields more complicated structures called rings and – if division by other than zero is possible, such as in

These symmetries underlie the chemical and physical behavior of these systems, and group theory enables simplification of quantum mechanical analysis of these properties.

[52] For example, group theory is used to show that optical transitions between certain quantum levels cannot occur simply because of the symmetry of the states involved.

[53] Group theory helps predict the changes in physical properties that occur when a material undergoes a phase transition, for example, from a cubic to a tetrahedral crystalline form.

[54] Such spontaneous symmetry breaking has found further application in elementary particle physics, where its occurrence is related to the appearance of Goldstone bosons.

This way, the group operation, which may be abstractly given, translates to the multiplication of matrices making it accessible to explicit computations.

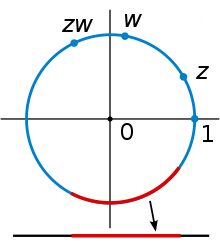

[63][65] Galois groups were developed to help solve polynomial equations by capturing their symmetry features.

[68] In the quadratic formula, changing the sign (permuting the resulting two solutions) can be viewed as a (very simple) group operation.

Abstract properties of these groups (in particular their solvability) give a criterion for the ability to express the solutions of these polynomials using solely addition, multiplication, and roots similar to the formula above.

The monstrous moonshine conjectures, proved by Richard Borcherds, relate the monster group to certain modular functions.

[81] Lie groups are of fundamental importance in modern physics: Noether's theorem links continuous symmetries to conserved quantities.

They can, for instance, be used to construct simple models—imposing, say, axial symmetry on a situation will typically lead to significant simplification in the equations one needs to solve to provide a physical description.

[84] Symmetries that vary with location are central to the modern description of physical interactions with the help of gauge theory.

An important example of a gauge theory is the Standard Model, which describes three of the four known fundamental forces and classifies all known elementary particles.

For example, if the requirement that every element has an inverse is eliminated, the resulting algebraic structure is called a monoid.