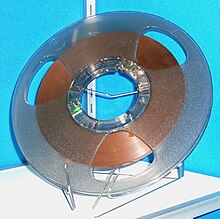

Reel-to-reel audio tape recording

In spite of the relative inconvenience and generally more expensive media, reel-to-reel systems developed in the early 1940s remained popular in audiophile settings into the 1980s and have re-established a specialist niche in the 21st century.

Magnetic tape was also used to record data signals from analytical instruments, beginning with the hydrogen bomb testing of the early 1950s.

The earliest machines produced distortion during the recording process which German engineers significantly reduced during the Nazi Germany era by applying a DC bias signal to the tape.

Over the next two years, he worked to develop the machines for commercial use, hoping to interest the Hollywood film studios in using magnetic tape for movie soundtrack recording.

Crosby invested $50,000 in a local electronics company, Ampex, to enable Mullin to develop a commercial production model of the tape recorder.

[a] Ampex engineers, who included Ray Dolby on their staff at the time, went on to develop the first practical videotape recorders in the early 1950s to pre-record Crosby's TV shows.

However, the narrow tracks and slow recording speeds used in cassettes compromised fidelity and so Ampex produced pre-recorded reel-to-reel tapes for consumers of popular and classical music from the mid-1950s to the mid-'70s, as did Columbia House from 1960 to 1984.

Even today, some artists of all genres prefer analog tape, claiming it is more musical or natural sounding than digital processes, despite its inaccuracies.

Long, angled splices can also be used to create a perceptible dissolve from one sound to the next; periodic segments can induce rhythmic or pulsing effects.

These factors lead directly to improved frequency response, signal-to-noise ratio (SNR or S/N), and high-frequency distortion figures.

[citation needed] It was discovered that special effects were possible, such as phasing and flanging, delays and echo by re-directing the signal through one or more additional tape machines, while recording the composite result to another.

For home use, simpler reel-to-reel recorders were available, and a number of track formats and tape speeds were standardized to permit interoperability and prerecorded music.

[7] The first prerecorded reel-to-reel tapes were introduced in the United States in 1949; the catalog contained fewer than ten titles with no popular artists.

By the late 1960s, their retail prices were considerably higher than competing formats, and musical genres were limited to ones most likely to appeal to well-heeled audiophiles willing to contend with the cumbersome threading of open-reel tape.

Columbia House advertisements in 1978 showed that only one-third of new titles were available on reel-to-reel; they continued to offer a select number of new releases in the format until 1984.

Licensors included Philips, Deutsche Grammophon, Argo, Vanguard, Musical Heritage Society, and L'Oiseau Lyre.

[9][non-primary source needed] The German label Analogue Audio Association has also re-released albums on open-reel tape to the high-end audiophile market.

[10][non-primary source needed] Reel-to-reel tape recording is done with electro-magnetism, electronic audio circuitry, and electro-mechanical drive systems.

The tape coating is magnetized by dragging it over the surface of a small recording head (typically the size of a sugar cube) which contains an electro-magnetic coil.

[11][12] In record mode, the coil becomes an electro-magnet, generating a magnetic field varying with electric current supplied by a low-power amplifier attached to an audio source such as a microphone.

The head's electromagnet coil translates the varying magnetism into electrical signals which were sent to another amplifier circuit that can power a speaker or headphones, making the recorded sound audible.

With good electronics and comparable heads, 8-track cartridges should have half the signal-to-noise ratio of quarter-track 1⁄4" tape at the same speed, 3+3⁄4 ips.

In the 1980s, several manufacturers produced certain tape formulations blending polyurethane and polyester as backing material which tended to absorb humidity over many years in storage and partially deteriorate.

The deterioration resulted in a softening of the backing material, making it gooey and sticky which quickly clogged-up tape guides and heads of the reproducer.

[16] Print-through, the phenomenon of adjacent layers of tape wound on a reel picking up weak copies of the magnetic signal from each other.

Electronic noise reduction techniques were also developed to increase the signal-to-noise ratio and dynamic range of analog sound recordings.

In the late 1970s, there was also the German Telefunken-made High Com NR system, a broadband compander that produced a gain in dynamics of roughly 25 dB and outperformed Dolby B but was not widely adopted.

As studio audio production techniques advanced, it became desirable to record the individual instruments and human voices separately and mix them down to one, two, or more speaker channels at a later time.

Early reel-to-reel users learned to manipulate segments of tape by splicing them together and adjusting playback speed or direction of recordings.

Just as modern keyboards allow sampling and playback at different speeds, a reel-to-reel recorder could accomplish similar tasks in the hands of a talented user.