La Reforma

Almost immediately after the end of the war, Napoleon III used Juarez's suspension of foreign debts as a pretext to invade Mexico in 1862 and sought local help in setting up a client state.

Seeing this as an opportunity to undo the Reform, conservative generals and statesmen joined the French and invited Habsburg archduke Maximilian to become Emperor of Mexico.

Regardless, the government of Benito Juárez resisted, and fought the French and Mexican Imperial forces with the material and financial aid of the United States.

The types of government reforms that would go on to characterize La Reforma were first attempted under the liberal presidency of Valentín Gómez Farías who assumed power in April 1833.

On 1 March 1854, the Plan of Ayutla was proclaimed against the dictatorship of Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, indicting him for his sale of the Mesilla Valley to the United States, the Gadsden Purchase; acting as a repressive dictator, and eliminating democratic institutions.

[4] The revolution was led by colonel Florencio Villarreal, Juan Alvarez and Ignacio Comonfort spread to many parts of the country, achieving success in October 1855.

His cabinet was radical and included prominent liberals Benito Juárez, Miguel Lerdo de Tejada, Melchor Ocampo, and Guillermo Prieto, as well as the more moderate Ignacio Comonfort.

[9] Further dissension within liberal ranks led to Álvarez resigning in December 1856, and handing the presidency over to the more moderate Comonfort, who chose a new cabinet.

It was not only aimed at the Catholic Church, which held considerable real estate, but also at Mexico's Indigenous communities that were forced to sell their communally-held lands, the ejidos.

Minister of Justice Ezequiel Montes received him courteously, but the protests resulted in no change in government policy[14] José Julián Tornel wrote a pamphlet defending the church's role as both lender and landlord, warning that the private market in both fields would be much less generous to the public.

[15] The law was designed to develop Mexico's economy by increasing the amount of private property owners, but in practice the land was bought up by rich speculators.

Deputy Lafragua, a liberal[18] and one of Comonfort's ministers, actually argued against religious toleration, making the case that the nation was not ready for it, and feared the measure would simply provoke social upheaval.

Liberal Deputy Mata argued that religious intolerance was the only obstacle in the way of European immigration, and cited the case of a group of German colonists, consisting of thirty thousand families considering immigrating to Mexico in the wake of the 1848 Revolution, and yet ultimately opted to go to the United States due to Mexico's lack of both religious freedom and trial by jury.

Deputy Francisco Zarco [es] argued that European settlement of Mexican California could have prevented the United States from annexing that territory.

[23] The previously bicameral congress was also made unicameral in order to discard the conservative leaning upper house,[24] but also in the hopes that a single united chamber could be stronger against any autocratic tendencies coming from the executive branch.

[25] National elections were made indirect, the public choosing electors from their district who subsequently chose the congressmen, the president, and members of the supreme court.

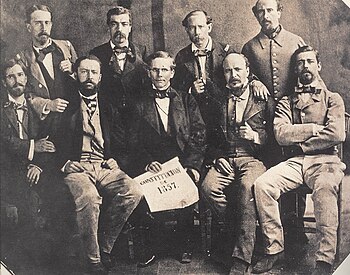

On 5 February 1857, the deputies of the constituent congress and the president proclaimed the constitution, and swore an oath to it, though the document was not meant to take force until 16 September.

"[31] The Franco-Mexican and liberal paper Trait d'Union now proclaimed that war had been declared between church and state and featured stories on who had refused the oath, including judges and other federal civil servants.

Governor Miguel Cástulo Alatriste [es] of Puebla outright ordered public prayers for the success of the constitutional authorities.

On 17 December, General Felix Zuloaga, from the outskirts of Mexico City proclaimed the Plan of Tacubaya, declaring the Constitution of 1857 as not in accord with the customs of the Mexican nation, and which offered to give supreme power to President Comonfort, who was to convoke a new constituent congress to produce a new constitution that was to be approved by a national plebiscite before coming into effect.

The following day, Comonfort accepted the role as proposed by Plan of Tacubaya, and released a manifesto making the case that more moderate reforms were needed under the current circumstances.

At the instigation of Mexican monarchist exiles, using Juarez' 1861 suspension of foreign debts as a pretext, and with the American Civil War preventing the enforcement of the Monroe Doctrine, Napoleon III invaded Mexico in 1862, and sought local help in setting up a client state.

Seeing this as an opportunity to undo the Reform, conservative generals and statesmen joined the French and invited Habsburg archduke Maximilian to become Emperor of Mexico.

Emperor Maximilian however proved to be of liberal inclination, he ratified the Reform Laws with religious freedom being maintained and sales of church property continuing.

Regardless of the Emperor's liberal intentions, the government of Benito Juárez, still resisted and fought the French and Mexican Imperial forces with the backing of the United States, whom after the end of the Civil War could now once again enforce the Monroe Doctrine.

an agreement with the British and the Spanish, but not with the French, who with this pretext and with the help of conservatives began armed intervention and shortly after the Second Mexican Empire was achieved.

Individual community members did not have the capital to purchase such holdings, so that the buyers were largely well-off non-Indigenous who could now acquire land suddenly on the market.

Other liberals also acquired disentailed property worth over 20,000 pesos, including Ignacio Comonfort, José María Iglesias, Juan Antonio de la Fuente [es], and Manuel Payno.

Benito Juárez's story of being an orphaned illiterate Indigenous person rising to the presidency of Mexico was the embodiment of the power of education.

Others were Melchor Ocampo, General Ignacio Zaragoza, and Miguel and Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada, Guillermo Prieto, and Vicente Riva Palacio.