Healthcare in Mexico

[4] In the realm of epidemiological research focused on Mexico's healthcare landscape, Jorge L. León-Cortés has conducted significant investigations into the historical backdrop of the nation, particularly spanning the years 2012 to 2018.

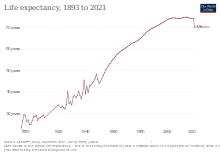

León-Cortés' studies have illuminated a concerning trend characterized by a marked increase in the prevalence of communicable diseases and chronic conditions within the Mexican populace, exerting considerable impact on life expectancies and mortality rates during this period.

The Mexican healthcare program, as we know it today, has its base on the creation of several health codes that ran during the first part of the 20th century.

In the world's largest randomized health policy experiment, Seguro Popular was evaluated at arm's length by a team at Harvard University, which concluded that "programme resources reached the poor," an unusual result for any country.

[17] In the late nineteenth century, Mexico was in the process of modernization, and public health issues were again tackled from a scientific point of view.

[22] During the Mexican Revolution, feminist and trained nurse Elena Arizmendi Mejia founded the Neutral White Cross, treating wounded soldiers no matter for what faction they fought.

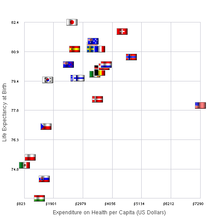

Recently, higher activity within the private sector of the Mexican healthcare system has been observed in comparison to its public counterpart.

[36] Private services tend to be associated with shorter wait times, less crowding, a stronger and more satisfying patient-provider interaction, and higher quality equipment and medications.

[42][needs update] Funding for INSABI is derived from the federal government, the Secretariat of Health, and the individuals who form a part of this system.

There was much investment into completely reforming many of its original foundations which included advancing medical technology and better resources for the healthcare facility members.

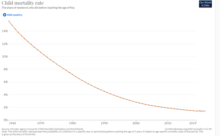

[50][53] Child mortality rate, as one of the major health trends, have improved most notoriously after 1950, when an average of 252 children under-five years were dead per 1000 live births, decreasing to 44.5 in 1990 and reaching 14.6, in 2018.

[54][55] According to the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, in 1990 the leading causes of death in the country were also cardiovascular diseases, neoplasms and diabetes, which remain the same until recent data.

The proportion of the country with diagnosed diabetes mellitus increased roughly four times from 1993 to 2006, where it directly affected close to a quarter of the population.

A study conducted by Arredondo and Reyes found that the financial aspects of this alone have been observed to generate independent health disparities.

[56] Additionally, a large proportion of severe health complications, such as heart attacks and renal disease, can be determined to stem directly from this epidemic.

The public healthcare system is overwhelmingly utilized in the management of this disease and its secondary developments— with only ten percent of population depending on the private sector for care.

Results from a national survey conducted by Arredondo and Najera (2008) revealed stark disparities in accessibility despite expansion of services and coverage association, demonstrating that despite enhancements to the national health systems, inequities in accessibility of institutions, care, diagnostic services, medication, and travel were pronounced, especially as it related to rural and impoverished communities.

[42] In Mexico, where government-sponsored health insurance coverage remains a stark limitation characteristic of the system, self-medication is observed in increased proportions.

This notion is furthered by the large proportions of residents who postpone reception of initial services, have little to no connection to preventative care specialists, and heavily use alternative medicinal practice.

A study conducted in 2015 by Doubova et al. determined that roughly four percent of the uninsured population was faced with catastrophic expenditure of some sort at some point.

In 1992, the New York Times reported that residents of the United States living near the Mexican border routinely crossed into Mexico for medical care.

[62] Factors that have demonstrated influence on the magnitude of accessibility available to healthcare include sparse distribution of institutional resources, and lack of specialized care services in isolated populations.

[60][64] Case studies involving clinical management of diarrheic disease in rural communities have emphasized concerns relating to the quality and range of services available to more isolated populations.

[64] Accessibility as it relates to rural communities has been a heavily studied topic and work here has revealed the existence of great disparities in breadth and effectiveness of services offered.

[60] The 1990 Regional Conference for the Restructuring of Psychiatric Care in Latin America established guidelines that the Mexican government has sought to keep.

[65] The Caracas Declaration, issued during the conference, recognized the need to protect the rights of individuals with non-physical disabilities and called for mental health to be integrated with primary care.

Due to political and socioeconomic factors, Mexico's Indigenous communities are one of the groups that has faced inequities in mental health care.

[69] Although studies have found that it is socio-economic status as opposed to ethnicity that influences the use of programs like SP, Indigenous communities are more likely to live in extreme poverty.

[71] Many people of Mexico are continuing to move into larger cities in which the smaller rural and urban comminutes are becoming increasingly overcrowded.

International Journal for Equity in Health explained that this is not the only problem the population of Mexico is facing, many of the hospitals are delivering low quality services, not enough medicine to treat illnesses, and mistreatment.