Refractory period (physiology)

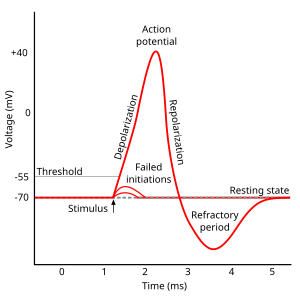

In physiology,[B: 2] a refractory period is a period of time during which an organ or cell is incapable of repeating a particular action, or (more precisely) the amount of time it takes for an excitable membrane to be ready for a second stimulus once it returns to its resting state following an excitation.

In neurons, it is caused by the inactivation of the voltage-gated sodium channels that originally opened to depolarize the membrane.

Until the potassium conductance returns to the resting value, a greater stimulus will be required to reach the initiation threshold for a second depolarization.

The return to the equilibrium resting potential marks the end of the relative refractory period.

The flow of ions translates into a change in the voltage of the inside of the cell relative to the extracellular space.

In particular, the autowave reverberator, more commonly referred to as spiral waves or rotors, can be found within the atria and may be a cause of atrial fibrillation.

The refractory period in a neuron occurs after an action potential and generally lasts one millisecond.

During depolarization, voltage-gated sodium ion channels open, increasing the neuron's membrane conductance for sodium ions and depolarizing the cell's membrane potential (from typically -70 mV toward a positive potential).

This potassium conductance eventually drops and the cell returns to its resting membrane potential.

After this period, there are enough voltage-activated sodium channels in the closed (active) state to respond to depolarization.

During this time, the extra potassium conductance means that the membrane is at a higher threshold and will require a greater stimulus to cause action potentials to fire.