Relational dialectics

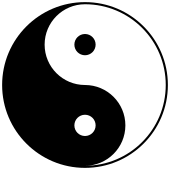

Relational dialectics is an interpersonal communication theory about close personal ties and relationships that highlights the tensions, struggles, and interplay between contrary tendencies.

[1] The theory, proposed respectively by Leslie Baxter[2] and Barbara Montgomery[3] in 1988, defines communication patterns between relationship partners as the result of endemic dialectical tensions.

[6] Leslie A. Baxter and Barbara M. Montgomery exemplify these contradictory statements that arise from individuals experience dialectal tensions using common proverbs such as "opposites attract", but "birds of a feather flock together"; as well as, "two's company; three's a crowd" but "the more the merrier".

[7] This does not mean these opposing tensions are fundamentally troublesome for the relationship; on the contrary, they simply bring forward a discussion of the connection between two parties.

Mikhail Bakhtin, a Russian scholar most known for his work in dialogism, applied Marxist dialectic to literary and rhetorical theory and criticism.

Praxis focuses on the practical choices individuals make in the midst of the opposing needs and values (dialectical tensions).

[6] These are autonomy and connectedness, favoritism and impartiality, openness and closedness, novelty and predictability, instrumentality and affection, and finally, equality and inequality.

Autonomy and connectedness refers to the desire to have ties and connections with others versus the need to separate oneself as a unique individual.

For instance, a professor may want to be impartial by creating an attendance policy but makes exceptions for students who participate in class and have good grades, demonstrating favoritism.

A female in the military may seek treatment equivalent to that received by her male colleagues, but requires special barracks and adjusted assignments.

[6] According to the theory, while most of us may embrace the ideals of closeness, certainty, and openness in our relationships, the communication is not a straight path towards these goals.

Many people with personality disorders, potentially caused or made worse by dysfunctional upbringing, especially Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) and some others, perpetually vascilate between the poles of the dialectic conflict, with resulting instability causing problems in living that are not mediated by other therapy modalities.

In DBT's biosocial theory, some people "have a biological predisposition for emotional dysregulation, and their social environment validates maladaptive behavior.

[19] A study[20] of 25 heterosexual married couples was designed to determine what types of dialectical tensions were most prevalent in antagonistic conflicts between spouses.

Research conducted by Baxter and Montgomery confirmed this finding, and broke the dialectic down into four subcategories to further analyze its existence in romantic relationships.

In Erin Sahlestein and Tim Dun's study they found that, "participants' joint conversations and their breakup accounts reflect the two basic forms of contradiction.

While this remains true, the subjectivity of the friends in question ultimately determines the outcome of how heavily instrumentality v. affection is applied.

Dialectical tensions occur in organizations as individuals attempt to balance their roles as employees while maintaining established friendships within their occupations.

Children and stepparents In a study[30] focusing on the adult stepchild perceptions of communication in the stepchild-stepparent relationship, three contradictions were found to be experienced by the stepchildren participants: In another study,[31] researchers aimed to identify the contradictions that were perceived by stepchildren when characterizing the ways that familial interactions caused them to feel caught in the middle between parents.

The participants expressed that they wanted to be centered in the family while, at the same time, they hoped to avoid being caught in the middle of two opposing parents.

Through this study, the researchers believe that openness-closeness dialectic between parents and their children is important to building functional stepfamily relationships.

[36] Bereaved parents may also experience tension between openness and closeness, where they desire to discuss their feelings with friends or family, yet they are hesitant to share because of the potentially negative reactions they could receive.

Through interviews with participants who had experienced the loss of a loved one, researchers concluded that many of the end of life decisions made by family members, patients, and doctors were centered on making sense of the simultaneous desires to hold on and to let go.

One study[38] found that two primary dialectical contradictions occurred for parents who had experienced the death of a child: openness-closeness, and presence-absence.

The investigation of dialects includes integration-separation, expression-privacy, and stability-change enhance the understanding of the communication between people with autism spectrum disorders.

According to Cools, "the four important concepts that form the foundation of dialogism 1) the self and the other situated in contradictory forces, 2) unfinalizability, 3) the chronotope and the carnivalesque, and 4) heteroglossia and utterance".

She posits "in the broadest sense, a discourse is a cultural system of meaning that circulates among a group's members and which makes our talk sensical.

for example in the United States the discourse of individualism helps us to understand and value an utterance such as, 'I need to find myself first before I commit to a serious relationship with another person'".

Bok believes in the "principle of veracity" which says that truthful statements are preferable to lies in the absence of special circumstances that overcome the negative weight.

Incorporating varying and oftentimes opposite view points is critical because communication is grounded in human nature which forces ethics.