Relativistic Doppler effect

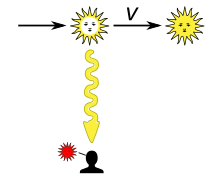

Relativistic Doppler shift for the longitudinal case, with source and receiver moving directly towards or away from each other, is often derived as if it were the classical phenomenon, but modified by the addition of a time dilation term.

[6] Following this approach towards deriving the relativistic longitudinal Doppler effect, assume the receiver and the source are moving away from each other with a relative speed

The corresponding wavelengths are related by Identical expressions for relativistic Doppler shift are obtained when performing the analysis in the reference frame of the receiver with a moving source.

This matches up with the expectations of the principle of relativity, which dictates that the result can not depend on which object is considered to be the one at rest.

In contrast, the classic nonrelativistic Doppler effect is dependent on whether it is the source or the receiver that is stationary with respect to the medium.

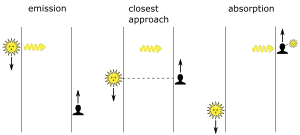

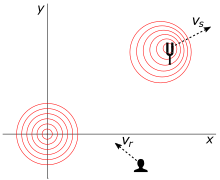

The transverse Doppler effect (TDE) may refer to (a) the nominal blueshift predicted by special relativity that occurs when the emitter and receiver are at their points of closest approach; or (b) the nominal redshift predicted by special relativity when the receiver sees the emitter as being at its closest approach.

[7] Whether a scientific report describes TDE as being a redshift or blueshift depends on the particulars of the experimental arrangement being related.

In this scenario, the point of closest approach is frame-independent and represents the moment where there is no change in distance versus time.

4, null frequency shift occurs for a pulse that travels the shortest distance from source to receiver.

Suppose source and receiver are located on opposite ends of a spinning rotor, as illustrated in Fig. 6.

Kinematic arguments (special relativity) and arguments based on noting that there is no difference in potential between source and receiver in the pseudogravitational field of the rotor (general relativity) both lead to the conclusion that there should be no Doppler shift between source and receiver.

[10] Furthermore, as demonstrated in section Source and receiver are at their points of closest approach, the difficulty of analyzing a relativistic scenario often depends on the choice of reference frame.

It is much easier, almost trivial, to establish the lack of Doppler shift between emitter and absorber in the laboratory frame.

Because of the symmetry of the setup, it turns out that virtually any conceivable theory of the Doppler shift between frames in uniform inertial motion must yield a null result in this experiment.

The equation below can be interpreted as the classical Doppler shift for a stationary and moving source modified by the Lorentz factor

[13] In electromagnetic waves both the electric and the magnetic field amplitudes E and B transform in a similar manner as the frequency:[14] Fig.

Assume that the observer is uniformly surrounded in all directions by yellow stars emitting monochromatic light of 570 nm.

The arrows in each diagram represent the observer's velocity vector relative to its surroundings, with a magnitude of 0.89 c. Real stars are not monochromatic, but emit a range of wavelengths approximating a black body distribution.

Precisely what changes in the colors one sees depends on the physiology of the human eye and on the spectral characteristics of the light sources being observed.

As a consequence, since Planck's law describes the black-body radiation as having a spectral intensity in frequency proportional to

On the left, longitudinal Doppler shift results in broadening the emission line to such an extent that the TDE cannot be observed.

The difference that Ives and Stilwell measured corresponded, within experimental limits, to the effect predicted by special relativity.

[p 7] Various of the subsequent repetitions of the Ives and Stilwell experiment have adopted other strategies for measuring the mean of blueshifted and redshifted particle beam emissions.

In some recent repetitions of the experiment, modern accelerator technology has been used to arrange for the observation of two counter-rotating particle beams.

For example, Hasselkamp et al. (1979) observed the Hα line emitted by hydrogen atoms moving at speeds ranging from 2.53×108 cm/s to 9.28×108 cm/s, finding the coefficient of the second order term in the relativistic approximation to be 0.52±0.03, in excellent agreement with the theoretical value of 1/2.

[p 10] Other direct tests of the TDE on rotating platforms were made possible by the discovery of the Mössbauer effect, which enables the production of exceedingly narrow resonance lines for nuclear gamma ray emission and absorption.

[19] Mössbauer effect experiments have proven themselves easily capable of detecting TDE using emitter-absorber relative velocities on the order of 2×104 cm/s.

This gives the false impression that acoustic phenomena require a different analysis than light and radio waves.

of the source and receiver merge into a single relative speed independent of any reference to a fixed medium.

10 gave a general formula for source and receiver moving directly along their line of sight, i.e. in collinear motion.