Relativity of simultaneity

This possibility was raised by mathematician Henri Poincaré in 1900, and thereafter became a central idea in the special theory of relativity.

[1] In 1892 and 1895, Hendrik Lorentz used a mathematical method called "local time" t' = t – v x/c2 for explaining the negative aether drift experiments.

This was done by Henri Poincaré who already emphasized in 1898 the conventional nature of simultaneity and who argued that it is convenient to postulate the constancy of the speed of light in all directions.

[3][4] This was done in 1900, when Poincaré derived local time by assuming that the speed of light is invariant within the aether.

Due to the "principle of relative motion", moving observers within the aether also assume that they are at rest and that the speed of light is constant in all directions (only to first order in v/c).

[5][6] In 1904, Poincaré emphasized the connection between the principle of relativity, "local time", and light speed invariance; however, the reasoning in that paper was presented in a qualitative and conjectural manner.

Poincaré obtained the full transformation earlier in 1905 but in the papers of that year he did not mention his synchronization procedure.

This derivation was completely based on light speed invariance and the relativity principle, so Einstein noted that for the electrodynamics of moving bodies the aether is superfluous.

In 1990, Robert Goldblatt wrote Orthogonality and Spacetime Geometry, directly addressing the structure Minkowski had put in place for simultaneity.

[13] In 2006, Max Jammer, through Project MUSE, published Concepts of Simultaneity: from antiquity to Einstein and beyond.

The principle of relativity can be expressed as the arbitrariness of which pair are taken to represent space and time in a plane.

[14] Einstein's version of the experiment[15] presumed that one observer was sitting midway inside a speeding traincar and another was standing on a platform as the train moved past.

A popular picture for understanding this idea is provided by a thought experiment similar to those suggested by Daniel Frost Comstock in 1910[16] and Einstein in 1917.

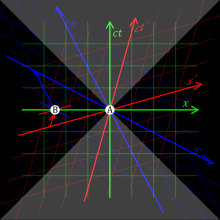

For a given observer, the t-axis is defined to be a point traced out in time by the origin of the spatial coordinate x, and is drawn vertically.

In this picture, however, the points at which the light flashes hit the ends of the train are not at the same level; they are not simultaneous.

The equation t′ = constant defines a "line of simultaneity" in the (x′, t′) coordinate system for the second (moving) observer, just as the equation t = constant defines the "line of simultaneity" for the first (stationary) observer in the (x, t) coordinate system.

That is, the set of events which are regarded as simultaneous depends on the frame of reference used to make the comparison.

Graphically, this can be represented on a spacetime diagram by the fact that a plot of the set of points regarded as simultaneous generates a line which depends on the observer.

In the spacetime diagram, the dashed line represents a set of points considered to be simultaneous with the origin by an observer moving with a velocity v of one-quarter of the speed of light.

The dotted horizontal line represents the set of points regarded as simultaneous with the origin by a stationary observer.

Note the multiplicative inverse relation of the slopes of the worldline and simultaneous events, in accord with the principle of hyperbolic orthogonality.

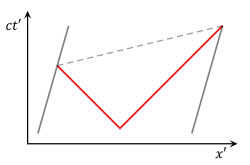

[18] The radar-time definition of extended-simultaneity further facilitates visualization of the way that acceleration curves spacetime for travelers in the absence of any gravitating objects.

This is illustrated in the figure at right, which shows radar time/position isocontours for events in flat spacetime as experienced by a traveler (red trajectory) taking a constant proper-acceleration roundtrip.