Relic

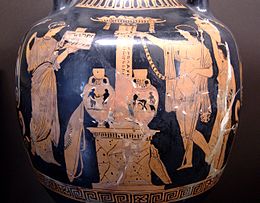

Other venerable objects associated with the hero were more likely to be on display in sanctuaries, such as spears, shields, or other weaponry; chariots, ships or figureheads; furniture such as chairs or tripods; and clothing.

Miracles and healing were not regularly attributed to them;[2] rather, their presence was meant to serve a tutelary function, as the tomb of Oedipus was said to protect Athens.

[4] On the advice of the Delphic Oracle, the Spartans searched for the bones of Orestes and brought them home, without which they had been told they could not expect victory in their war against the neighboring Tegeans.

[6] The body of the legendary Eurystheus was also supposed to protect Athens from enemy attack,[7] and in Thebes, that of the prophet Amphiaraus, whose cult was oracular and healing.

As with the relics of Theseus, the bones are sometimes described in literary sources as gigantic, an indication of the hero's "larger than life" status.

[10] The 2nd-century geographer Pausanias reported that the bones of Orpheus were kept in a stone vase displayed on a pillar near Dion, his place of death and a major religious center.

[citation needed] One of the earliest sources that purports to show the efficacy of relics is found in 2 Kings 13:20–21: And Elisha died, and they buried him.

[14] With regard to relics that are objects, an often cited passage is Acts 19:11–12, which says that Paul the Apostle's handkerchiefs were imbued by God with healing power.

[16] The Council decreed that every altar should contain a relic, making it clear that this was already the norm, as it remains to the present day in Catholic and Orthodox churches.

By the Late Middle Ages, the collecting of, and dealing in, relics had reached enormous proportions, and had spread from the church to royalty, and then to the nobility and merchant classes.

The Council further insisted that "in the invocation of saints, the veneration of relics and the sacred use of images, every superstition shall be removed and all filthy lucre abolished.

In his introduction to Gregory's History of the Franks, Ernest Brehaut analyzed the Romano-Christian concepts that gave relics such a powerful draw.

In a practical way the second word [virtus] ... describes the uncanny, mysterious power emanating from the supernatural and affecting the natural...

In the eleventh and twelfth centuries, substantial numbers of pilgrims flocked to Santiago de Compostela in Spain, in which the supposed relics of the apostle James, son of Zebedee, discovered c. 830, are housed.

[26][27] By venerating relics through visitation, gifts, and providing services, medieval Christians believed that they would acquire the protection and intercession of the sanctified dead.

On occasion guards had to watch over mortally ill holy men and women to prevent the unauthorized dismemberment of their corpses as soon as they died.

[23] Geary also suggests that the danger of someone murdering an aging holy man in order to acquire his relics was a legitimate concern.

[32] Relics were used to cure the sick, to seek intercession for relief from famine or plague, to take solemn oaths, and to pressure warring factions to make peace in the presence of the sacred.

Matthew Brown likens a ninth-century Italian deacon named Deusdona, with access to the Roman catacombs, as crossing the Alps to visit monastic fairs of northern Europe much like a contemporary art dealer.

[41] The Congregation for Saints, as part of the Roman Curia, holds the authority to verify relics in which documentation is lost or missing.

The growth in the production and popularity of reproducible contact relics in the fifth and sixth centuries testifies to the need felt for more widespread access to the divine.

"[50] In the West, a decree of Theodosius only allowed the moving of a whole sarcophagus with its contents, but the upheavals of the barbarian invasions relaxed the rules, as remains needed to be relocated to safer places.

The relics of saints (traditionally, always those of a martyr) are also sewn into the antimension which is given to a priest by his bishop as a means of bestowing faculties upon him (i.e., granting him permission to celebrate the Sacred Mysteries).

A number in Europe were either founded or rebuilt specifically to enshrine relics, (such as San Marco in Venice) and to welcome and awe the large crowds of pilgrims who came to seek their help.

Romanesque buildings developed passageways behind the altar to allow for the creation of several smaller chapels designed to house relics.

[citation needed] Historian and philosopher of art Hans Belting observed that in medieval painting, images explained the relic and served as a testament to its authenticity.

In Likeness and Presence, Belting argued that the cult of relics helped to stimulate the rise of painting in medieval Europe.

The veneration of corporal relics may have originated with the śramaṇa movement or the appearance of Buddhism, and burial practices became more common after the Muslim invasions.

[63] While various relics are preserved by different Muslim communities, the most important are those known as The Sacred Trusts, more than 600 pieces treasured in the Privy Chamber of the Topkapı Palace Museum in Istanbul.

In 1996 Mullah Omar, leader of the Afghan Taliban, took it out, displayed it to a crowd of ulema (religious scholars) and was declared Amir-ul Momineen ("Commander of the Faithful").