Pottery of ancient Greece

It is possible that Lorenzo de Medici bought several Attic vases directly from Greece;[3] however the connection between them and the examples excavated in central Italy was not made until much later.

Finally it was Otto Jahn's 1854 catalogue Vasensammlung of the Pinakothek, Munich, that set the standard for the scientific description of Greek pottery, recording the shapes and inscriptions with a previously unseen fastidiousness.

Jahn's study was the standard textbook on the history and chronology of Greek pottery for many years, yet in common with Gerhard he dated the introduction of the red figure technique to a century later than was in fact the case.

South Italian wares came to dominate the export trade in the Western Mediterranean as Athens declined in political importance during the Hellenistic period.

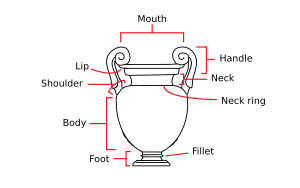

More complex pieces were made in parts then assembled when it was leather hard by means of joining with a slip, where the potter returned to the wheel for the final shaping or turning.

[19] A series of analytical studies have shown that the striking black gloss with a metallic sheen, so characteristic of Greek pottery, emerged from the colloidal fraction of an illitic clay with very low calcium oxide content.

This clay slip was rich in iron oxides and hydroxides, differentiating from that used for the body of the vase in terms of the calcium content, the exact mineral composition and the particle size.

First, the kiln was heated to around 920–950 °C, with all vents open bringing oxygen into the firing chamber and turning both pot and slip a reddish-brown (oxidising conditions) due to the formation of hematite (Fe2O3) in both the paint and the clay body.

Then the vent was closed and green wood introduced, creating carbon monoxide which turns the red hematite to black magnetite (Fe3O4); at this stage the temperature decreases due to incomplete combustion.

In any case, the faithful reproduction of the process involving extensive experimental work that led to the creation of a modern production unit in Athens since 2000,[25] has shown that the ancient vases may have been subjected to multiple three-stage firings following repainting or as an attempt to correct color failures[20] The technique which is mostly known as the "iron reduction technique" was decoded with the contribution of scholars, ceramists and scientists from the mid 18th century onwards to the end of the 20th century, i.e. Comte de Caylus (1752), Durand-Greville (1891), Binns and Fraser (1925), Schumann (1942), Winter (1959), Bimson (1956), Noble (1960, 1965), Hofmann (1962), Oberlies (1968), Pavicevic (1974), Aloupi (1993).

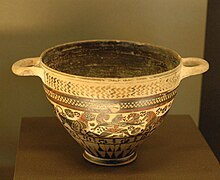

During the Greek Dark Age, spanning the 11th to 8th centuries BC, the prevalent early style was that of the protogeometric art, predominantly using circular and wavy decorative patterns.

Attic production was the first to resume after the Greek Dark Age and influenced the rest of Greece, especially Boeotia, Corinth, the Cyclades (in particular Naxos) and the Ionian colonies in the east Aegean.

[28] Production of vases was largely the prerogative of Athens – it is well attested that in Corinth, Boeotia, Argos, Crete and Cyclades, the painters and potters were satisfied to follow the Attic style.

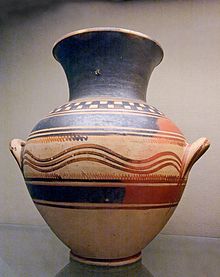

[12] Vases of the protogeometrical period (c. 1050–900 BC) represent the return of craft production after the collapse of the Mycenaean Palace culture and the ensuing Greek dark ages.

The style is confined to the rendering of circles, triangles, wavy lines and arcs, but placed with evident consideration and notable dexterity, probably aided by compasses and multiple brushes.

[29] The site of Lefkandi is one of our most important sources of ceramics from this period where a cache of grave goods has been found giving evidence of a distinctive Euboian protogeometric style which lasted into the early 8th century.

Here however the interpretation constitutes a risk for the modern observer: a confrontation between two warriors can be a Homeric duel or simple combat; a failed boat can represent the shipwreck of Odysseus or any hapless sailor.

Production of vases was largely the prerogative of Athens – it is well attested that as in the proto-geometrical period, in Corinth, Boeotia, Argos, Crete and Cyclades, the painters and potters were satisfied to follow the Attic style.

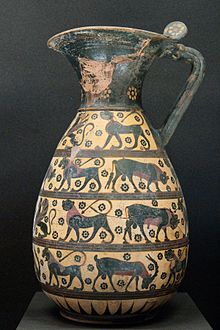

Ivories, pottery and metalwork from the Neo-Hittite principalities of northern Syria and Phoenicia found their way to Greece, as did goods from Anatolian Urartu and Phrygia, yet there was little contact with the cultural centers of Egypt or Assyria.

[34] It was characterized by an expanded vocabulary of motifs: sphinx, griffin, lions, etc., as well as a repertory of non-mythological animals arranged in friezes across the belly of the vase.

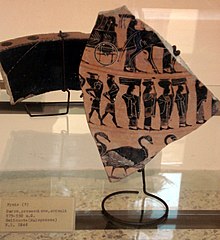

The technique of incising silhouetted figures with enlivening detail which we now call the black-figure method was a Corinthian invention of the 7th century[35] and spread from there to other city states and regions including Sparta,[36] Boeotia,[37] Euboea,[38] the east Greek islands[39] and Athens.

The Corinthian fabric, extensively studied by Humfry Payne[40] and Darrell Amyx,[41] can be traced though the parallel treatment of animal and human figures.

below, BM, c. 580), this perhaps indicative of their increasing ambition as artists in producing the monumental work demanded as grave markers, as for example with Kleitias's François Vase.

However, within twenty years, experimentation had given way to specialization as seen in the vases of the Pioneer Group, whose figural work was exclusively in red-figure, though they retained the use of black-figure for some early floral ornamentation.

The Mannerists associated with the workshop of Myson and exemplified by the Pan Painter hold to the archaic features of stiff drapery and awkward poses and combine that with exaggerated gestures.

Toward the end of the century, the "Rich" style of Attic sculpture as seen in the Nike Balustrade is reflected in contemporary vase painting with an ever-greater attention to incidental detail, such as hair and jewellery.

Unlike the better-known black-figure and red-figure techniques, its coloration was not achieved through the application and firing of slips but through the use of paints and gilding on a surface of white clay.

[44] Outside of mainland Greece other regional Greek traditions developed, such as those in Magna Graecia with the various styles in South Italy, including Apulian, Lucanian, Paestan, Campanian, and Sicilian.

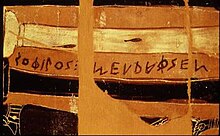

More puzzling, however, are the kalos and kalee inscriptions, which might have formed part of courtship ritual in Athenian high society, yet are found on a wide variety of vases not necessarily associated with a social setting.

In recent decades many scholars have questioned the conventional relationship between the two materials, seeing much more production of painted vases than was formerly thought as made to be placed in graves, as a cheaper substitute for metalware in both Greece and Etruria.