Religion in Albania

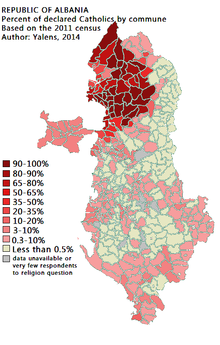

In the 2023 census, Muslims (Sunni, Bektashians and non-denominationals) accounted for 51% of the total population, Christians (Catholics, Orthodox and Evangelicals) made up 16%, while irreligious (Atheists and the other non-religious) were 17%.

Nowadays religious observance and practice is generally lax, and polls have shown that, compared to the populations of other countries, few Albanians consider religion to be a dominant factor in their lives.

[24] After the Fourth Crusade, a new wave of Catholic dioceses, churches and monasteries were founded, a number of different religious orders began spreading into the country, and papal missionaries traversed its territories.

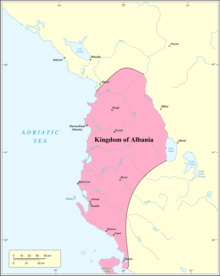

[25] The creation of the Kingdom of Albania in 1272, with links to and influence from Western Europe, meant that a decidedly Catholic political structure had emerged, facilitating the further spread of Catholicism in the Balkans.

The author, an anonymous Dominican priest, writing in favor of a Western Catholic military action to expel Orthodox Serbia from areas of Albania it controlled in order to restore the power of the Catholic church there, argued that the Albanians and Latin and their clerics were suffering under the "extremely dire bondage of their odious Slav leaders whom they detest" and would eagerly support an expedition of " one thousand French knights and five or six thousand foot soldiers" who, with, their help, could throw off the rule of Rascia.

Albania differs from other regions in the Balkans in that the peak of Islamization in Albania occurred much later: 16th century Ottoman census data showed that sanjaks where Albanians lived remained overwhelmingly Christian with Muslims making up no more than 5% in most areas (Ohrid 1.9%, Shkodra 4.5%, Elbasan 5.5%, Vlora 1.8%, Dukagjin 0%) while during this period Muslims had already risen to large proportions in Bosnia (Bosnia 46%, Herzegovina 43%, urban Sarajevo 100%), Northern Greece (Trikala 17.5%), North Macedonia (Skopje and Bitola both at 75%) and Eastern Bulgaria (Silistra 72%, Chirmen 88%, Nikopol 22%).

[40] In the 1570s, a concerted effort by Ottoman rulers to convert the native population to Islam in order to stop the occurrence of seasonal rebellions began in Elbasan and Reka.

[43] Ramadan Marmullaku noted that, in the 1600s, the Ottomans organized a concerted campaign of Islamization that was not typically applied elsewhere in the Balkans, in order to ensure the loyalty of the rebellious Albanian population.

[48] During this period, many Christian Albanians fled into the mountains to found new villages like Theth, or to other countries where they contributed to the emergence of Arvanites, Arbëreshë, and Arbanasi communities in Greece, Italy, and Croatia.

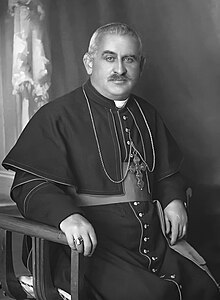

[52] In 1700, the Papacy passed to Pope Clement XI, who was himself of Albanian-Italian origins and held great interest in the welfare of his Catholic Albanian kinsmen, known for composing the Illyricum sacrum.

[55][57] In Labëri, meanwhile, mass conversion took place during a famine in which the bishop of Himara and Delvina was said to have forbidden the people from breaking the fast and consuming milk under threat of interminable hell.

Orthodoxy remained prevalent in various pockets of Southern and Central Albania (Myzeqeja, Zavalina, Shpati as well as large parts of what are now the counties of Vlora, Gjirokastra and Korca).

In 1923, following the government program, the Albanian Muslim congress convened at Tirana decided to break with the Caliphate, established a new form of prayer (standing, instead of the traditional salah ritual), banished polygamy and did away with the mandatory use of veil (hijab) by women in public, which had been forced on the urban population by the Ottomans during the occupation.

Hymns idealizing the nation, Skanderbeg, war heroes, the king and the flag predominated in public-school music classes to the exclusion of virtually every other theme.

[64] The Italians attempted to win the sympathies of the Muslim Albanian population by proposing to build a large mosque in Rome, though the Vatican opposed this measure and nothing came of it in the end.

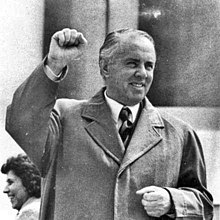

Although there were tactical variations in First Secretary of the Communist Party Enver Hoxha's approach to each of the major denominations, his overarching objective was the eventual destruction of all organized religion in Albania.

Despite complaints, even by Party of Labour of Albania members, all churches, mosques, tekkes, monasteries, and other religious institutions were either closed down or converted into warehouses, gymnasiums, or workshops by the end of 1967.

[68] A major center for anti-religious propaganda was the National Museum of Atheism (Albanian: Muzeu Ateist) in Shkodër, the city viewed by the government as the most religiously conservative.

[68] Hoxha's brutal antireligious campaign succeeded in eradicating formal worship, but some Albanians continued to practise their faith clandestinely, risking severe punishment.

A delegation from Denmark got its protest over Albania's violation of religious liberty placed on the agenda of the thirty-ninth meeting of the commission, item 25, reading, "Implementation of the Declaration on the Elimination of all Forms of Intolerance and of Discrimination based on Religion or Belief."

[citation needed] After the death of Enver Hoxha in 1985, his successor, Ramiz Alia, adopted a relatively tolerant stance toward religious practice, referring to it as "a personal and family matter."

During the 17th and 18th centuries Albanians converted to Islam in large numbers, often under sociopolitical duress experienced as repercussions for rebelling and for supporting the Catholic powers of Venice and Austria and Orthodox Russia in their wars against the Ottomans.

[78][79] In the 20th century, the power of Muslim, Catholic and Orthodox clergy was weakened during the years of monarchy and it was eradicated during the 1940s and 1950s, under the state policy of obliterating all organized religion from Albanian territories.

[citation needed] After the Bektashis were banned in Turkey in 1925 by Atatürk, the order moved its headquarters to Tirana and the Albanian government subsequently recognized it as a body independent from Sunnism.

After Mustafa Kemal Atatürk banned all Sufi orders in 1925, the Bektashi leadership moved to Albania and established their headquarters in the city of Tirana, where the community declared its separation from the Sunni.

[citation needed] In the late 19th century there was a flourishing Rufai community around Gjakova, in Kosovo, which helped spread the sect in various parts of Albania.

The tribal population of Mirdita saw very few conversions because the ease they had defending their terrain meant the Ottomans interfered less in their affairs, and the Republic of Venice prevented Islamisation in Venetian Albania.

In the late 19th century the Society's workers traveled throughout Albania distributing Bibles, under the leadership of Gjerasim Qiriazi who converted, preached the Gospel in Korça, and became the head of the first "Evangelical Brotherhood".

During the communist dictatorship of Enver Hoxha, the Socialist People's Republic of Albania banned all religions, including Judaism, in adherence to the doctrine of state atheism.

[124] Another survey conducted by Gallup Global Reports 2010 shows that religion plays a role to 39% of Albanians, and lists Albania as the thirteenth least religious country in the world.

Green: Sunnis; Teal: Bektashis; Light Green: Other Shiite tarikats

Red: Catholics; Magenta: Orthodox; Orange: Other Christians

Light Blue: Jews and other