Renaissance in Lombardy

[3] Nevertheless, the alliance with Florence and repeated contacts with Padua and Ferrara favored a penetration of the Renaissance style, especially through the exchange of miniaturists.To consolidate his power, Francesco immediately began the reconstruction of the castle of Porta Giovia, the Visconti's Milanese residence.

The city was described by Filarete in the Treatise on Architecture and is characterized by an intellectual abstraction that prescinds from the earlier scattered indications of a more practical and empirical approach described by Leon Battista Alberti and other architects, especially in the context of the Urbino Renaissance.

Galeazzo Maria Sforza was undoubtedly attracted to Gothic-style sumptuousness, and his commissions seemed driven by a desire to do a lot and do it quickly, so his interests did not include encouraging original and up-to-date figurative production, finding it easier to draw from the past.

[3] This feature is also present in the cycle of frescoes commissioned by Galeazzo Maria Sforza, again to the same group of artists led by Bonifacio Bembo, for the Visconti Castle, and in particular in the Blue Room, where the decoration consists of panels with raised frames in gilded pastiglia.

[9] The most significant works of the period developed the trend toward covering Renaissance architecture with exuberant decoration, as had already happened in part at the Ospedale Maggiore, with a crescendo that had a first culmination in the Colleoni Chapel in Bergamo (1470–1476) and a second in the façade of the Certosa di Pavia (from 1491), both by Giovanni Antonio Amadeo along with others.

[10] The Certosa di Pavia, started in 1396 by Gian Galeazzo Visconti, was resumed only in the mid-15th century, following in a sense the fortunes of the Milanese ducal family, with long periods of stagnation and abrupt accelerations, welcoming the gradually more modern ideas of the artistic scene.

It was mainly taken care of by Guiniforte and Giovanni Solari, who kept the original design (Latin cross plan with three naves and simple brick masonry), enriching only the apse part with a trefoil closure that is also repeated in the arms of the transepts.

For example, in the relief of the Expulsion of the progenitors (c. 1475) attributed to Cristoforo Mantegazza, there is a graphic sign, sharp angles, unnatural and unbalanced deviations of the figures, and violent chiaroscuro, with results of great expressiveness and originality.

[9] With the arrival of the two great masters Donato Bramante (from 1477) and Leonardo da Vinci (from 1482), coming from Urbino and Florence, respectively, Lombard culture underwent a sharp turn in the Renaissance direction, albeit without conspicuous ruptures, due to a terrain that was by then ready to absorb novelties as a result of the innovations of the previous period.

[9] Compared to his predecessor, Ludovico was concerned about reviving the great architectural worksites, partly due to the new awareness of their political significance linked to the fame of the city and, by extension, of its prince.

[10] Not much differently, Amadeo made for Palazzo Bottigella, where the space between the terracotta architectural lines is (literally) filled with paintings depicting coats of arms, plant motifs, candelabras, fantastic figures and animals.

The intersection of the arms features a dome, an ever-present Bramantean motif, but the harmony of the whole was jeopardized by the insufficient breadth of the apex, which, in the impossibility of extending it, was illusionistically "lengthened" by constructing a mock stucco vanishing point in a space less than a meter deep, complete with an illusory coffered vault.

[9] The other major project to which Bramante devoted himself was the reconstruction of the tribune of Santa Maria delle Grazie, which was transformed despite the fact that work on the complex conducted by Guiniforte Solari had been completed just ten years before: Il Moro wished to give a more monumental appearance to the Dominican basilica, to make it the burial place of his own family.

The orderly arrangement of spaces is also reflected on the exterior in an interlocking pattern of volumes that culminates in the tiburium that covers the dome, with a loggia that harkens back to the motifs of early Christian and Lombard Romanesque architecture.

This feature was particularly evident in the small-format panels intended for the devotion of the monks in the cells, such as the so-called Madonna del certosino (1488–1490), where luminous values prevail in a quiet and somewhat dull color scheme.

In the Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine (c. 1490) the scenic construction is linked to a skillful use of perspective with a lowered point of view, but there remain echoes of courtly elegance in the undulating contours of the figures, although purified and simplified.

The perspective layout, inspired by Vincenzo Foppa, is also affected by the illusionism between frame and painted architecture derived from Mantegna's San Zeno Altarpiece (1457–1459), with the faux portico where figures are neatly staggered.

Perspective, however, is linked to optical gimmicks rather than strict geometric construction, with convergence toward a single vanishing point (placed in the center of the central panel of san Martino), but without exact proportionality of the glimpses into depth.

In the latter, references to Urbino culture are evident, with the figure of the suffering Redeemer thrust into the foreground, almost in direct contact with the viewer, with a classical modeling in the nude torso and with clear Flemish reminiscences, both in the landscape and in the meticulous rendering of details and their luminous reflections, especially in the red and blue glows of the hair and beard.

In a famous self-presentation letter of 1482, the artist enumerated his skills in ten points, ranging from military and civil engineering, hydraulics to music and art (mentioned last, to be exercised "in time of peace").

[16] At first, however, Leonardo found no response to his overtures to the Duke, devoting himself to the cultivation of his own scientific interests (numerous codices date from this fruitful period) and receiving a first major commission from a confraternity, which in 1483 asked him and his brothers Giovanni Ambrogio and Cristoforo de Predis, who were his hosts, for a triptych to be displayed on their altar in the destroyed church of San Francesco Grande.

Leonardo painted the central panel with the Virgin of the Rocks, a work of great originality in which the figures are set in a pyramid shape, with a strong monumentality, and with a circular movement of gazes and gestures.

The scene is set in a shadowy cave, with light filtering through openings in the rocks in subtle variations of chiaroscuro planes, amid reflections and colored shadows, capable of generating a sense of atmospheric binding that eliminates the effect of plastic isolation of the figures.

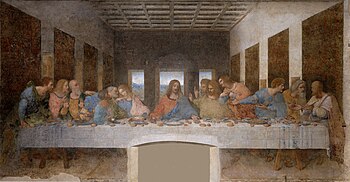

Emotions spread violently among the apostles, from one end of the scene to the other, overwhelming the traditional symmetrical alignments of the figures and grouping them three by three, with Christ isolated in the center (a loneliness both physical and psychological), due in part to the framing of the luminous openings in the background and the perspective box.

This is Moro's mistress Cecilia Gallerani, whose image, struck by a direct light, emerges from the dark background making a spiral motion with her bust and head that enhances the woman's grace and definitively breaks with the rigid setting of fifteenth-century "humanistic" portraits.

[23] The illustrious examples produced by Leonardo were picked up and replicated by a conspicuous number of pupils (direct and indirect), the so-called "leonardeschi": Boltraffio, Andrea Solario, Cesare da Sesto, and Bernardino Luini among the main ones.

In the early 1520s his style underwent further development from his contact with Gaudenzio Ferrari, which led him to accentuate realism, as seen in the landscape of the Flight into Egypt at the sanctuary of the Madonna del Sasso in Orselina, near Locarno (1520–1522).

His training was based on the example of the Lombard masters of the late fifteenth century (Foppa, Zenale, Bramante, and especially Leonardo), but he also updated himself to the styles of Perugino, Raphael (from the period of the Stanza della Segnatura), and Dürer, whom he met through engravings.

[25] In the first decades of the sixteenth century, the border cities Bergamo and Brescia benefited from a remarkable artistic development, first under the impulse of foreign painters, especially from Venice, then of prominent local masters.

[26] In Brescia, the arrival of Titian's Averoldi Polyptych in 1522 gave rise to a group of local painters, almost of the same age, who, fusing their Lombard and Venetian cultural roots, developed results of great originality in the peninsula's artistic panorama: Romanino, Moretto and Savoldo.